Paintings Listed by Ohio County - J-P

JACKSON

“Little Wales”

Many settlers of the new state of Ohio came from Wales – either directly or from settlements in the northeastern states. One migration in 1818 landed many families in southeastern Ohio and another major one in 1839 brought so many Welsh families that the area of Jackson and Gallia counties became known as “Little Wales.” Today the village of Oak Hill maintains the Welsh-American Heritage Museum, the only one of its kind in the United States. And, the population of Jackson County is still a whopping ten percent today. Who knows, perhaps a Welshman built this barn?

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

JEFFERSON

“The Surveyors”

Most people don’t know that General George Washington, our first president, began his career as a land surveyor. And, in his travels in the Ohio Country in the late 1700s, he might have been near this barn, which, of course, wasn’t built at that time. I found it on the whirlwind tour of Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, sitting next to State Route 43, just east of Amsterdam. When he was 16, Washington accompanied two prominent surveyors for work in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, not far from his family farm which he inherited when his father died. A year later in 1749, he was appointed the official surveyor for Culpeper County in Virginia. This led to an appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment in the French and Indian War in the 1750s. His war service earned him land grants in the Ohio River valley, which motivated him to explore the area in 1770. He and others took a canoe trip from present day Pittsburgh down the Ohio River and found the land ideal for settlement. In fact, he purchased land in Ohio and West Virginia and surveyed it after the war. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Most people don’t know that General George Washington, our first president, began his career as a land surveyor. And, in his travels in the Ohio Country in the late 1700s, he might have been near this barn, which, of course, wasn’t built at that time. I found it on the whirlwind tour of Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, sitting next to State Route 43, just east of Amsterdam. When he was 16, Washington accompanied two prominent surveyors for work in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, not far from his family farm which he inherited when his father died. A year later in 1749, he was appointed the official surveyor for Culpeper County in Virginia. This led to an appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment in the French and Indian War in the 1750s. His war service earned him land grants in the Ohio River valley, which motivated him to explore the area in 1770. He and others took a canoe trip from present day Pittsburgh down the Ohio River and found the land ideal for settlement. In fact, he purchased land in Ohio and West Virginia and surveyed it after the war. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

KNOX

“The Saltbox of Ohio”

This tiny barn, nearly touching busy Ohio Route 229, attracted my attention immediately. Its rusted roof had just the right amount of red and brown in it and the occasional orange and red streaks in the siding enhanced its artistic flair. Some missing and warped boards added to its charm, as did the small window, its white paint still bright, and its haymow door, swung wide open, almost as if it were inviting strangers from the nearby road. The roof was dramatically asymmetrical – one side was short and the other was much longer, sloping down the hill. But my barn scout had no information on it. By luck, a neighbor noticed us milling around the barn and asked us for our credentials – since drug-related crime is on the rise in rural communities. After I explained our mission, the lady gave us contact information for Jeff DePolo, the owner.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This tiny barn, nearly touching busy Ohio Route 229, attracted my attention immediately. Its rusted roof had just the right amount of red and brown in it and the occasional orange and red streaks in the siding enhanced its artistic flair. Some missing and warped boards added to its charm, as did the small window, its white paint still bright, and its haymow door, swung wide open, almost as if it were inviting strangers from the nearby road. The roof was dramatically asymmetrical – one side was short and the other was much longer, sloping down the hill. But my barn scout had no information on it. By luck, a neighbor noticed us milling around the barn and asked us for our credentials – since drug-related crime is on the rise in rural communities. After I explained our mission, the lady gave us contact information for Jeff DePolo, the owner.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“The Wool Barn”

Not many barns capture my imagination, but this one did. The composition is one of my favorites – the railway fading from next to the barn and then into the horizon, framed by diminishing green trees, the gray barn fronted by a red and white railroad crossing pole, and colorful hardwoods on both sides. Today Janelle, Larry’s daughter, and her husband Cory Ladig own this barn on Sycamore Road, in the area known as "Hunt's Station" in the old days - after the original train station. They live in a house that used to be the general store. Larry told me that a larger barn near this one, now gone, used to house sheep along with their wool.

When Larry and I visited it in the fall of 2017, he told me that it was a barn used to store wool from the many sheep farms in Knox County. When the train arrived, workers loaded wool onto the trains for shipment to factories. This continued into the 1940s – a time when Knox County was the largest wool producing county east of the Mississippi.

Wouldn’t this have been a sight to see? Go back to the 1800s. Farmers approach the barn, hauling their wool stored in wagons, drawn by horses. Men unloading. Then the whistle of the train alerts workmen to rise and shine and throw open the barn doors – to move wool into rail cars. Nowadays the barn looks forsaken, its paint gone and boards weathered. Only one train comes by a day. But there was a time when …

Not many barns capture my imagination, but this one did. The composition is one of my favorites – the railway fading from next to the barn and then into the horizon, framed by diminishing green trees, the gray barn fronted by a red and white railroad crossing pole, and colorful hardwoods on both sides. Today Janelle, Larry’s daughter, and her husband Cory Ladig own this barn on Sycamore Road, in the area known as "Hunt's Station" in the old days - after the original train station. They live in a house that used to be the general store. Larry told me that a larger barn near this one, now gone, used to house sheep along with their wool.

When Larry and I visited it in the fall of 2017, he told me that it was a barn used to store wool from the many sheep farms in Knox County. When the train arrived, workers loaded wool onto the trains for shipment to factories. This continued into the 1940s – a time when Knox County was the largest wool producing county east of the Mississippi.

Wouldn’t this have been a sight to see? Go back to the 1800s. Farmers approach the barn, hauling their wool stored in wagons, drawn by horses. Men unloading. Then the whistle of the train alerts workmen to rise and shine and throw open the barn doors – to move wool into rail cars. Nowadays the barn looks forsaken, its paint gone and boards weathered. Only one train comes by a day. But there was a time when …

LAKE

“Aunt Ruth’s Perfume Factory”

I had almost given up trying to find a barn in Lake County, established in 1840 and highly developed. Though the smallest in land size, it ranks 11th in population and it’s jam packed with people, schools, and businesses and, as one might guess, it also lacks the flavor of a rural county and its old barns. I had a nibble from a lady who owns a chicken farm – but no old barn – but that fizzled. So, I decided to re-visit my Ohio Bicentennial Barn book, found the barn painted in Lake County that was done in 2002, called the county auditor, and send a snail mail letter to the owner, Thomas Carrig. Dan and Jennifer Hearn, co-owners with his uncle Thomas and mother Nancy, sent me a speedy email reply. Yes, I could visit.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

I had almost given up trying to find a barn in Lake County, established in 1840 and highly developed. Though the smallest in land size, it ranks 11th in population and it’s jam packed with people, schools, and businesses and, as one might guess, it also lacks the flavor of a rural county and its old barns. I had a nibble from a lady who owns a chicken farm – but no old barn – but that fizzled. So, I decided to re-visit my Ohio Bicentennial Barn book, found the barn painted in Lake County that was done in 2002, called the county auditor, and send a snail mail letter to the owner, Thomas Carrig. Dan and Jennifer Hearn, co-owners with his uncle Thomas and mother Nancy, sent me a speedy email reply. Yes, I could visit.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

LAWRENCE

“Castle on the Hill”

An article in the Ironton Tribune newspaper caught the attention of Kay Swartzwelder, owner of this barn, along with her husband Scott. Since hers was the most interesting response, I scheduled a trip, which included my grandson Henry. Kay wrote that their farm was located close to Coal Grove, a village near the Ohio River, probably named for its coal mines, which were abundant in the nineteenth century in southern and eastern Ohio – along with numerous charcoal-fired blast furnaces, which were used to convert iron ore to iron, a significant factor in the Civil War.

Since finding her farm might be difficult, we met Kay at Giovanni’s Pizza – a restaurant that twelve-year-old Henry begged me to stop at – and followed her through some country lanes, finally arriving at the scene, which reminded me of the song, Castle on the Hill, written by Ed Sheeran and Benjamin Levin. We stopped at the base of the steep hill, which rises about 100 feet, so that I could include a tall Sycamore tree in the composition.

The barn was built around 1916, a date the saw-cut timbers affirm, but it wasn’t until 1933, in the throes of the Great Depression, that Scott’s grandfather acquired it. Eventually the farm passed to Scott, who may someday continue the family ownership with son Brandon, whom we met and who helped me select some of the old barn siding, virgin poplar, for the painting’s frame.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

An article in the Ironton Tribune newspaper caught the attention of Kay Swartzwelder, owner of this barn, along with her husband Scott. Since hers was the most interesting response, I scheduled a trip, which included my grandson Henry. Kay wrote that their farm was located close to Coal Grove, a village near the Ohio River, probably named for its coal mines, which were abundant in the nineteenth century in southern and eastern Ohio – along with numerous charcoal-fired blast furnaces, which were used to convert iron ore to iron, a significant factor in the Civil War.

Since finding her farm might be difficult, we met Kay at Giovanni’s Pizza – a restaurant that twelve-year-old Henry begged me to stop at – and followed her through some country lanes, finally arriving at the scene, which reminded me of the song, Castle on the Hill, written by Ed Sheeran and Benjamin Levin. We stopped at the base of the steep hill, which rises about 100 feet, so that I could include a tall Sycamore tree in the composition.

The barn was built around 1916, a date the saw-cut timbers affirm, but it wasn’t until 1933, in the throes of the Great Depression, that Scott’s grandfather acquired it. Eventually the farm passed to Scott, who may someday continue the family ownership with son Brandon, whom we met and who helped me select some of the old barn siding, virgin poplar, for the painting’s frame.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

LICKING

"Granville Gray"

This old boy was the spark that started my fire to paint Ohio's old barns. Its owner gave me history about the area and the barn, which made for a good essay. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

A TV producer drove two hours from his office in Columbus to feature this barn in the Spectrum News video (December, 2019). It comes just as the car rises above a hill.

Click here for a look.

This old boy was the spark that started my fire to paint Ohio's old barns. Its owner gave me history about the area and the barn, which made for a good essay. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

A TV producer drove two hours from his office in Columbus to feature this barn in the Spectrum News video (December, 2019). It comes just as the car rises above a hill.

Click here for a look.

LOGAN

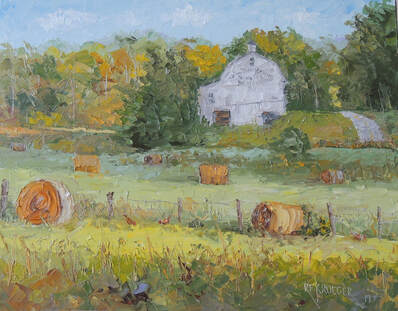

“Hay Heaven”

Barn scout Bob Stoll and I met Russ Miller, who owns this farm with his wife Beth, on a sunny day in April, 2023. Russ, a retired math teacher and dairy farmer, has lived here since 1973. Two years later, his father purchased the farm. Along with dairying, they used to raise beef cattle on this spread of 143 acres. Today Russ and his brother farm hay, evidenced by the long line of neatly arranged hay bales in the foreground.

The large barn with its metal gambrel roof – a style that allowed more storage than the simple gable roof – has been meticulously maintained. Inside, mortise and tenon joints and sawcut lumber hint that this barn was a transition from purely timber framing to plank construction, probably dating it to the 1890-1910 period. A slight bank was built up to allow wagons to deliver hay to be stored and, formerly, as Russ explained, a cupola provided ventilation for livestock. One summer Russ had the task of stacking 9,000 bales of hay and straw in the second story of the barn. Whew! An add-on came later, hinting that the farmer needed more storage space and that he was prosperous enough to build a handsome brick foundation.

Russ mentioned that Neil Slicer may have been the farm’s founder in the Civil War era. Born in Maryland in 1814, he became a printer, working in that field for 10 years. In 1840 he moved to Bellefontaine and worked in printing for a short time – before he switched into the mercantile field. He again switched careers in 1852, when he bought a farm. He and his wife Sarah had eight children. Although over the years the farm has rotated through tenant farmers, today it’s purely hay heaven – and, fortunately, it’s in the hands of a custodian who counts it a privilege to care for it.

Barn scout Bob Stoll and I met Russ Miller, who owns this farm with his wife Beth, on a sunny day in April, 2023. Russ, a retired math teacher and dairy farmer, has lived here since 1973. Two years later, his father purchased the farm. Along with dairying, they used to raise beef cattle on this spread of 143 acres. Today Russ and his brother farm hay, evidenced by the long line of neatly arranged hay bales in the foreground.

The large barn with its metal gambrel roof – a style that allowed more storage than the simple gable roof – has been meticulously maintained. Inside, mortise and tenon joints and sawcut lumber hint that this barn was a transition from purely timber framing to plank construction, probably dating it to the 1890-1910 period. A slight bank was built up to allow wagons to deliver hay to be stored and, formerly, as Russ explained, a cupola provided ventilation for livestock. One summer Russ had the task of stacking 9,000 bales of hay and straw in the second story of the barn. Whew! An add-on came later, hinting that the farmer needed more storage space and that he was prosperous enough to build a handsome brick foundation.

Russ mentioned that Neil Slicer may have been the farm’s founder in the Civil War era. Born in Maryland in 1814, he became a printer, working in that field for 10 years. In 1840 he moved to Bellefontaine and worked in printing for a short time – before he switched into the mercantile field. He again switched careers in 1852, when he bought a farm. He and his wife Sarah had eight children. Although over the years the farm has rotated through tenant farmers, today it’s purely hay heaven – and, fortunately, it’s in the hands of a custodian who counts it a privilege to care for it.

“A Farmer’s Frigidaire”

Whoever built this old springhouse was a master at his craft. Well-cut quoins support the corners and, though there’s probably been some repair done, the mortar in this uncoursed rubble construction of fieldstone and limestone has held up remarkably well. Uncut logs support the second floor and a metal roof protects what was probably original wooden shakes. Barn scout Bob Stoll explained that the nearby farmhouse dates to 1830, which means that this springhouse can’t be far behind. From observation of the nearby Stoll barn’s foundation, it appears that the same stonemason did both structures.

Springhouses, as were root cellars – more rustic structures often built like a cave into a hillside – were probably the second most important part of an early farmstead, right behind the barn. Usually, settlers would erect a simple log home before the barn, but sometimes they’d build a barn first and live in it, along with their livestock and crops. After the barn came the springhouse, normally built over a well or a spring, where the water temperature remained around 55 degrees year-round, not as cold as a refrigerator but cold enough to store meat and vegetables. On the east coast, farmers built these structures in the 18th century and, as settlers moved into Ohio in the 19th century, they continued this tradition. Later, ice houses appeared, built to preserve a winter’s crop of ice. And, in time, as dairy farms developed, the functions of the springhouse included storing milk and eventually cheese products. When the electric refrigerator became popular in the late 1920s, the springhouse was relegated to a charming piece of history – as was another integral part of an early farmstead – the outhouse.

Few stone springhouses remain today, making this one extremely rare. Hopefully, Matt McGuire, who purchased it in 2010, will maintain it or donate it to the historical society to preserve it for future generations. Though its metal roof appears sturdy and though its masonry is mostly intact, one of the walls needs repair. With good fortune, this historic springhouse will continue to survive, answering the question schoolchildren may ask about how the early Ohioans kept their food cold. There weren’t any Frigidaires in those days.

Whoever built this old springhouse was a master at his craft. Well-cut quoins support the corners and, though there’s probably been some repair done, the mortar in this uncoursed rubble construction of fieldstone and limestone has held up remarkably well. Uncut logs support the second floor and a metal roof protects what was probably original wooden shakes. Barn scout Bob Stoll explained that the nearby farmhouse dates to 1830, which means that this springhouse can’t be far behind. From observation of the nearby Stoll barn’s foundation, it appears that the same stonemason did both structures.

Springhouses, as were root cellars – more rustic structures often built like a cave into a hillside – were probably the second most important part of an early farmstead, right behind the barn. Usually, settlers would erect a simple log home before the barn, but sometimes they’d build a barn first and live in it, along with their livestock and crops. After the barn came the springhouse, normally built over a well or a spring, where the water temperature remained around 55 degrees year-round, not as cold as a refrigerator but cold enough to store meat and vegetables. On the east coast, farmers built these structures in the 18th century and, as settlers moved into Ohio in the 19th century, they continued this tradition. Later, ice houses appeared, built to preserve a winter’s crop of ice. And, in time, as dairy farms developed, the functions of the springhouse included storing milk and eventually cheese products. When the electric refrigerator became popular in the late 1920s, the springhouse was relegated to a charming piece of history – as was another integral part of an early farmstead – the outhouse.

Few stone springhouses remain today, making this one extremely rare. Hopefully, Matt McGuire, who purchased it in 2010, will maintain it or donate it to the historical society to preserve it for future generations. Though its metal roof appears sturdy and though its masonry is mostly intact, one of the walls needs repair. With good fortune, this historic springhouse will continue to survive, answering the question schoolchildren may ask about how the early Ohioans kept their food cold. There weren’t any Frigidaires in those days.

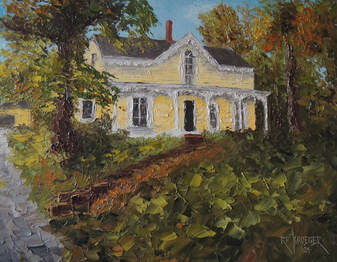

“Survival”

Benjamin Bunker built this charming farmhouse and the adjacent two barns between 1875 and 1880. Inside, there’s a mixture of hand hewn beams and saw-cut timbers, evidence of a sawmill nearby or on the farm. Over the years, owners used the barns to house sheep and cattle. Today it’s used for storage.

Current owners Bill and Susan Shultz were kind enough to give barn scout Bob Stoll and me a tour. They explained that the farm has been in family hands since 1929 – at the end of the turbulent 1920s – the roaring 20s in the big cities but painful years for farmers. A year later, the Great Depression began, but the Shultz family survived, unlike many farmers who lost their farms to banks. These days they allow a farming partner to raise corn and soybeans on most of their 600 acres and they continue to maintain these two historic barns, a testament to their ancestors, who managed to keep the farm during the perilous Great Depression and the war years. In those days, it was all about survival.

Benjamin Bunker built this charming farmhouse and the adjacent two barns between 1875 and 1880. Inside, there’s a mixture of hand hewn beams and saw-cut timbers, evidence of a sawmill nearby or on the farm. Over the years, owners used the barns to house sheep and cattle. Today it’s used for storage.

Current owners Bill and Susan Shultz were kind enough to give barn scout Bob Stoll and me a tour. They explained that the farm has been in family hands since 1929 – at the end of the turbulent 1920s – the roaring 20s in the big cities but painful years for farmers. A year later, the Great Depression began, but the Shultz family survived, unlike many farmers who lost their farms to banks. These days they allow a farming partner to raise corn and soybeans on most of their 600 acres and they continue to maintain these two historic barns, a testament to their ancestors, who managed to keep the farm during the perilous Great Depression and the war years. In those days, it was all about survival.

“Booze Days”

Jerry Fitzpatrick, who owns this barn, along with his two sisters, gave barn scout Bob Stoll and me a tour of this interesting bank barn. His ancestor, also a Fitzpatrick, founded the farm in the late 1800s and hired someone to build this barn in 1895. This year and the initials, “FHC,” are painted in blue on one of the beams. He also included the exact date, September 21, likely the barn raising day, which the builder must have been pretty proud of.

The barn, a three bay English threshing type, represents the transition from the ancient art of timber framing with hand-hewn beams, cut often from trees on the property. Though there are some mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs, the lumber is mostly sawn.Though it’s mostly an English design, the barn has a short forebay on the rear side, a German tradition and its wooden shake roof, now protected by metal, may be original. Six decorative louvers on the front add flair and their ventilation hints that livestock were housed here. Feeding stalls on the bottom level and rectangular ventilators on the ends provide more evidence of this. The rock foundation is an impressive display of stonemasonry; little mortar was needed in between the large cut fieldstones.

The farm was also famous for its annual event of craft beer competitions, called Booze Days and held in June. This celebration involved two days of dancing, music, and craft beers, appealing to the many Germans in western Ohio – as well as to other beer lovers from adjacent states and even from as far west as California. It continued for 15 years before Jerry shut it down.

These days, nearby Bellefontaine, the county seat, has taken over the reins in sponsoring B-Town Brew Fest in the downtown area. Entry fees include 10 tasting tickets for samplings of Ohio-made beer, which feature a local artisan, Roundhouse Depot Brewing. Four Acre Clothing provides on-site screen printing of special edition shirts. Yes, Germans love their beer as did, most likely, the builder of this wonderful barn, who would have also enjoyed the Fitzpatrick’s Booze Days.

Jerry Fitzpatrick, who owns this barn, along with his two sisters, gave barn scout Bob Stoll and me a tour of this interesting bank barn. His ancestor, also a Fitzpatrick, founded the farm in the late 1800s and hired someone to build this barn in 1895. This year and the initials, “FHC,” are painted in blue on one of the beams. He also included the exact date, September 21, likely the barn raising day, which the builder must have been pretty proud of.

The barn, a three bay English threshing type, represents the transition from the ancient art of timber framing with hand-hewn beams, cut often from trees on the property. Though there are some mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs, the lumber is mostly sawn.Though it’s mostly an English design, the barn has a short forebay on the rear side, a German tradition and its wooden shake roof, now protected by metal, may be original. Six decorative louvers on the front add flair and their ventilation hints that livestock were housed here. Feeding stalls on the bottom level and rectangular ventilators on the ends provide more evidence of this. The rock foundation is an impressive display of stonemasonry; little mortar was needed in between the large cut fieldstones.

The farm was also famous for its annual event of craft beer competitions, called Booze Days and held in June. This celebration involved two days of dancing, music, and craft beers, appealing to the many Germans in western Ohio – as well as to other beer lovers from adjacent states and even from as far west as California. It continued for 15 years before Jerry shut it down.

These days, nearby Bellefontaine, the county seat, has taken over the reins in sponsoring B-Town Brew Fest in the downtown area. Entry fees include 10 tasting tickets for samplings of Ohio-made beer, which feature a local artisan, Roundhouse Depot Brewing. Four Acre Clothing provides on-site screen printing of special edition shirts. Yes, Germans love their beer as did, most likely, the builder of this wonderful barn, who would have also enjoyed the Fitzpatrick’s Booze Days.

“Shawver’s Sparkling Legacy”

Barn scout Bob Stoll saved this barn until the end of our tour in April, 2023. Yes, it wasn’t in good shape; its red paint was peeling away from its gray undersides, pieces of the metal roof were torn off, and some siding and doors were missing. It needed serious help. Fortunately, Scott and Missy Buroker, who recently purchased this 10-acre farm, explained that they planned to restore the historic barn. That was welcome news since the barn traces back nearly 130 years – evidenced by lettering on the front, “Shady-Nook, 1894.” John Shawver built it. His great-great-grandson Chuck Gamble showed us a wooden model of barn construction that John used to show to prospective farmers, who were thinking about hiring him. Shawver, a well-documented Ohio barn builder, revolutionized barn building by using a new approach, which not only saved building time but did not require massive beams and timber framing. He built over 7,000 barns in the United States and Canada. Since this essay centers on an Ohio barn builder, an important part of early Ohio history, it is lengthy and, as such, is too long for this site; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

Barn scout Bob Stoll saved this barn until the end of our tour in April, 2023. Yes, it wasn’t in good shape; its red paint was peeling away from its gray undersides, pieces of the metal roof were torn off, and some siding and doors were missing. It needed serious help. Fortunately, Scott and Missy Buroker, who recently purchased this 10-acre farm, explained that they planned to restore the historic barn. That was welcome news since the barn traces back nearly 130 years – evidenced by lettering on the front, “Shady-Nook, 1894.” John Shawver built it. His great-great-grandson Chuck Gamble showed us a wooden model of barn construction that John used to show to prospective farmers, who were thinking about hiring him. Shawver, a well-documented Ohio barn builder, revolutionized barn building by using a new approach, which not only saved building time but did not require massive beams and timber framing. He built over 7,000 barns in the United States and Canada. Since this essay centers on an Ohio barn builder, an important part of early Ohio history, it is lengthy and, as such, is too long for this site; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

“Seriously Stoll”

Barn scout Bob Stoll and his sister Deb, along with their spouses, own this old barn, which dates to the 19th century and to a farmer named Charles Folsom. Bob’s parents, Weldon and Barbara Stoll purchased the 250-acre farm in the 1970s and, when Barbara died in 2020, Bob and Deborah became the new owners.

Interestingly, Bob’s great grandfather Jacob Stoll was one of Ohio’s early barn builders, one of a group that, unfortunately, has not been well documented. Jacob built many timber-framed barns in Clark County, two counties south of Logan.

This barn, painted green, another rarity in Ohio, and its massive cement silo, probably added in the early 1900s, displays typical timber framing with mortise and tenon joints and hand-hewn beams. Original roof planks, which once supported wood shakes, are now wisely covered with metal, assuring many more years of longevity for the barn. A master stone mason built the foundation, which features beautifully-cut pieces of limestone, coursed in uniform rows. He might have also built the nearby stone springhouse, which originally was part of the farmstead.

Today, Bob uses the barn to house heifers and calves on his farm, which as a sign documents, is Ohio Preserved Farmland, part of the Logan County Land Trust, of which Bob is a director. Formerly a district conservationist, having worked for the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service, Bob has helped establish 23 other easements in his county, assuring that the land will be used only for agriculture and will not be allowed to be developed into housing or commercial property. Without a doubt, this farmstead is “seriously Stoll.”

Barn scout Bob Stoll and his sister Deb, along with their spouses, own this old barn, which dates to the 19th century and to a farmer named Charles Folsom. Bob’s parents, Weldon and Barbara Stoll purchased the 250-acre farm in the 1970s and, when Barbara died in 2020, Bob and Deborah became the new owners.

Interestingly, Bob’s great grandfather Jacob Stoll was one of Ohio’s early barn builders, one of a group that, unfortunately, has not been well documented. Jacob built many timber-framed barns in Clark County, two counties south of Logan.

This barn, painted green, another rarity in Ohio, and its massive cement silo, probably added in the early 1900s, displays typical timber framing with mortise and tenon joints and hand-hewn beams. Original roof planks, which once supported wood shakes, are now wisely covered with metal, assuring many more years of longevity for the barn. A master stone mason built the foundation, which features beautifully-cut pieces of limestone, coursed in uniform rows. He might have also built the nearby stone springhouse, which originally was part of the farmstead.

Today, Bob uses the barn to house heifers and calves on his farm, which as a sign documents, is Ohio Preserved Farmland, part of the Logan County Land Trust, of which Bob is a director. Formerly a district conservationist, having worked for the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service, Bob has helped establish 23 other easements in his county, assuring that the land will be used only for agriculture and will not be allowed to be developed into housing or commercial property. Without a doubt, this farmstead is “seriously Stoll.”

“Last Days”

This venerable old barn traces back to pre-Civil War times and, since it’s large, it may not have been the first barn on this farm, which is in its sixth generation of Hudson family ownership.

Jacob V. Hudson, patriarch and pioneer, settled this land in 1827 and began farming, hoping to take advantage of the Land Act of 1820, which reduced the number of acres that Ohioans had to purchase from 160 to 80 and the cost from $2.00 per acre to $1.25 per acre – an attempt to encourage additional land sales. He might also have used the Relief Act of 1821, which allowed Ohio farmers to return land back to the government, earning credit towards their debt. President Andrew Jackson signed the Hudson deed in April, 1829, which recorded the sale of 78 acres.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This venerable old barn traces back to pre-Civil War times and, since it’s large, it may not have been the first barn on this farm, which is in its sixth generation of Hudson family ownership.

Jacob V. Hudson, patriarch and pioneer, settled this land in 1827 and began farming, hoping to take advantage of the Land Act of 1820, which reduced the number of acres that Ohioans had to purchase from 160 to 80 and the cost from $2.00 per acre to $1.25 per acre – an attempt to encourage additional land sales. He might also have used the Relief Act of 1821, which allowed Ohio farmers to return land back to the government, earning credit towards their debt. President Andrew Jackson signed the Hudson deed in April, 1829, which recorded the sale of 78 acres.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

LORAIN

“Milking His Girls"

Lorain County, the county just west of Cleveland, is full of barns, unlike its neighbors, Cuyahoga and Lake counties. After the Chronicle, the county’s biggest newspaper, ran an article about my barn project, many barn owners inquired. Sadly, I had to turn down all but two, both located in the southern part of the county, which was easier for me to reach on this barn trip. I told the others that I’d return if a local nonprofit becomes interested in raising funds with my paintings. I met the barn owner, Dan Clark, an effervescent, extroverted former National Guard helicopter mechanic-turned-IT-expert. His job at Sherwin Williams takes him on projects around the world. Fortunately for me, his busy schedule allowed him to show me around his barn, one that he’s pretty proud of – and rightfully so. He also told me that his township of Pittsfield no longer has a post office and seems to be disappearing amid adjacent towns of Oberlin, Wellington, and LaGrange. The latter, a French word for “the farm,” symbolizes the heart of this area. As Dan said, “Agriculture is in our blood and we are generational stewards of the land, ensuring there is a farm to call home to some future generation that wants to put a plow in it.”

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Lorain County, the county just west of Cleveland, is full of barns, unlike its neighbors, Cuyahoga and Lake counties. After the Chronicle, the county’s biggest newspaper, ran an article about my barn project, many barn owners inquired. Sadly, I had to turn down all but two, both located in the southern part of the county, which was easier for me to reach on this barn trip. I told the others that I’d return if a local nonprofit becomes interested in raising funds with my paintings. I met the barn owner, Dan Clark, an effervescent, extroverted former National Guard helicopter mechanic-turned-IT-expert. His job at Sherwin Williams takes him on projects around the world. Fortunately for me, his busy schedule allowed him to show me around his barn, one that he’s pretty proud of – and rightfully so. He also told me that his township of Pittsfield no longer has a post office and seems to be disappearing amid adjacent towns of Oberlin, Wellington, and LaGrange. The latter, a French word for “the farm,” symbolizes the heart of this area. As Dan said, “Agriculture is in our blood and we are generational stewards of the land, ensuring there is a farm to call home to some future generation that wants to put a plow in it.”

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

LUCAS

“All American”

God smiled upon me as I drove through the western part of Lucas County, another Ohio county whose rural scene is becoming engulfed with industry and suburbs. Without any help from the county’s historical society, I was on my own, hoping for a good find – like the one I had discovered earlier in Wood County. Driving up Route 64 and crossing the Maumee River into Lucas territory, I noticed a red barn across a field. But it didn’t excite me. So I kept going, keeping it as a possibility, and turned onto Route 20, heading towards Swanton.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

God smiled upon me as I drove through the western part of Lucas County, another Ohio county whose rural scene is becoming engulfed with industry and suburbs. Without any help from the county’s historical society, I was on my own, hoping for a good find – like the one I had discovered earlier in Wood County. Driving up Route 64 and crossing the Maumee River into Lucas territory, I noticed a red barn across a field. But it didn’t excite me. So I kept going, keeping it as a possibility, and turned onto Route 20, heading towards Swanton.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MADISON

“The Constitution”

Madison County was the last county I visited on my six-day barn trip in the spring of 2019. Without any connections, I kept my eye out for any oldies on my drive down Route 38, heading through rural farm country and on my way to I-71 and home. As I passed the junction of this route and Old Xenia Road, I saw a beauty, a stunningly weathered brown barn with a small add-on, possibly a corn crib. With many boards missing, holes gaping through and through, the barn’s life was nearly over, something that a windstorm could finalize. It was my kind of barn.

I knocked on the adjacent farmhouse door but no one answered. Later I called the historical society but got no help. I even contacted the county auditor, who had trouble locating the owners. Anyway I sent a letter, but it was never answered. So I looked to the county for a story.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Madison County was the last county I visited on my six-day barn trip in the spring of 2019. Without any connections, I kept my eye out for any oldies on my drive down Route 38, heading through rural farm country and on my way to I-71 and home. As I passed the junction of this route and Old Xenia Road, I saw a beauty, a stunningly weathered brown barn with a small add-on, possibly a corn crib. With many boards missing, holes gaping through and through, the barn’s life was nearly over, something that a windstorm could finalize. It was my kind of barn.

I knocked on the adjacent farmhouse door but no one answered. Later I called the historical society but got no help. I even contacted the county auditor, who had trouble locating the owners. Anyway I sent a letter, but it was never answered. So I looked to the county for a story.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MAHONING

“Peter Pan, Wendy, and Tinkerbell”

Old barns sometimes, but not always, can tell a compelling story. However, once in a great while the barn reveals multiple looks into the past as this one does, the one I like to call “the Peter Pan barn.”

This barn, located many miles south of Youngstown’s once-famous steel mills, lies in the southern part of Mahoning County, where farming was the main economic engine – as it was in the adjacent Appalachian county of Columbiana. Sandra Ciminero, current co-owner and resident of this farm, told me that her grandfather, Ralph E. Elser, purchased the farm around 1921, though the farm traces back into the 1800s, as evidenced by a pile of old hand-hewn beams taken from an earlier building and according to a 1925 Elser reunion notice, which explained that a century earlier George Elser, the farm’s founder, traveled here with his family in a covered wagon drawn by two oxen. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Old barns sometimes, but not always, can tell a compelling story. However, once in a great while the barn reveals multiple looks into the past as this one does, the one I like to call “the Peter Pan barn.”

This barn, located many miles south of Youngstown’s once-famous steel mills, lies in the southern part of Mahoning County, where farming was the main economic engine – as it was in the adjacent Appalachian county of Columbiana. Sandra Ciminero, current co-owner and resident of this farm, told me that her grandfather, Ralph E. Elser, purchased the farm around 1921, though the farm traces back into the 1800s, as evidenced by a pile of old hand-hewn beams taken from an earlier building and according to a 1925 Elser reunion notice, which explained that a century earlier George Elser, the farm’s founder, traveled here with his family in a covered wagon drawn by two oxen. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Harter’s Heritage”

Though they’re vanishing quickly from farm fields, Ohio still has many majestic old barns left and this is one of the best. Ironically, it sits in Mahoning County, which is known mostly for the many steel mills of Youngstown and vicinity – rather than old barns. However, the southern end of the county still has a connection with its rural 19th-century beginnings. This impressive forebay bank barn traces back to Andrew and George Harter, 19th-century immigrants from Germany. What’s equally astounding is how the current owner came to buy the barn.

Jean Dougherty and her husband Peter own this barn in North Lima, an unincorporated community of 1,300 residents in eastern Beaver Township. They moved here from New Jersey, which made me wonder why someone from that heavily populated state would choose to live in rural northeastern Ohio. Jean explained that, even though she grew up in a suburb, she loved horses. In fact, when she was seven, her dad took her to a barn, which housed horses and fostered her love not only of horses but of barns. She loved playing in the barn, jumping into the haystacks, and playing in the clubhouse she made. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY ...

Though they’re vanishing quickly from farm fields, Ohio still has many majestic old barns left and this is one of the best. Ironically, it sits in Mahoning County, which is known mostly for the many steel mills of Youngstown and vicinity – rather than old barns. However, the southern end of the county still has a connection with its rural 19th-century beginnings. This impressive forebay bank barn traces back to Andrew and George Harter, 19th-century immigrants from Germany. What’s equally astounding is how the current owner came to buy the barn.

Jean Dougherty and her husband Peter own this barn in North Lima, an unincorporated community of 1,300 residents in eastern Beaver Township. They moved here from New Jersey, which made me wonder why someone from that heavily populated state would choose to live in rural northeastern Ohio. Jean explained that, even though she grew up in a suburb, she loved horses. In fact, when she was seven, her dad took her to a barn, which housed horses and fostered her love not only of horses but of barns. She loved playing in the barn, jumping into the haystacks, and playing in the clubhouse she made. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY ...

“Harter’s Heritage”

This barn has a long story but here's some more of it.

In 2017, after watching Barnwood Builders, a popular television series that began in 2013 – where a crew from West Virginia dismantles old barns and log cabins to repurpose them into homes – Jean decided to contact them. To her surprise, the star of the show, Mark Bowe, visited her to see the barn, which he described as “the best barn I’ve ever seen.” Yes, without question, Mark was a natural salesman. While going through the barn, he made a video of it, which was later posted on YouTube, pointing out its many unique features. Enthralled, he made an offer to buy it, but Jean turned him down. A student of history, Jean wanted to preserve this remarkable barn.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL STORY.

“The Canfield Cowboy”

The Anderson bicentennial farm represents ownership of this 200-acre farmstead from when Abraham Kline settled here, buying this land in 1814 for his son Jonathan – to present-day owner Wayne Anderson, whom I met in the fall of 2020. His sister, Linda Keylor, contacted me, thanks to a Vindicator story about my Ohio Barn Project, and encouraged me to visit, sending many newspaper articles about her interesting family, whose roots started in Germany.

George Klein (name eventually changed to Kline), born in Germany in 1719, came to America in 1738 and settled in Hosensack, Pennsylvania. He married, had three sons, and, besides being a prominent landowner, he started a tavern, the Buckhorn Hotel. In the American Revolution, he served in the Northampton Militia.

The Ohio history traces back to patriarch Abraham Kline, born in 1769 in Schuykill County, Pennsylvania, who journeyed west, presumably, for more land and less people. He settled on a farm on the banks of the Mahoning River in 1806. His biography in History of Trumbull and Mahoning County, states, “He was of German descent … stern, generous, and enterprising, persevering in business, but always kind and social in his dealings. His death occurred in the year 1816 … He accumulated a large estate, having farmed extensively and dealt successfully in livestock.” CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY

The Anderson bicentennial farm represents ownership of this 200-acre farmstead from when Abraham Kline settled here, buying this land in 1814 for his son Jonathan – to present-day owner Wayne Anderson, whom I met in the fall of 2020. His sister, Linda Keylor, contacted me, thanks to a Vindicator story about my Ohio Barn Project, and encouraged me to visit, sending many newspaper articles about her interesting family, whose roots started in Germany.

George Klein (name eventually changed to Kline), born in Germany in 1719, came to America in 1738 and settled in Hosensack, Pennsylvania. He married, had three sons, and, besides being a prominent landowner, he started a tavern, the Buckhorn Hotel. In the American Revolution, he served in the Northampton Militia.

The Ohio history traces back to patriarch Abraham Kline, born in 1769 in Schuykill County, Pennsylvania, who journeyed west, presumably, for more land and less people. He settled on a farm on the banks of the Mahoning River in 1806. His biography in History of Trumbull and Mahoning County, states, “He was of German descent … stern, generous, and enterprising, persevering in business, but always kind and social in his dealings. His death occurred in the year 1816 … He accumulated a large estate, having farmed extensively and dealt successfully in livestock.” CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY

MARION

“Seven Sisters”

Kay Lamb, current owner of this 150-acre farm, explained that Joseph Kester, a traveling Lutheran minister as well as a master carpenter, built the 1850-era farmhouse where her nephew David now lives. Kester may have built a barn at the time, but it didn’t last. In 1880 the Retterer family took over the farm and David Retterer built the present barn in 1886.

He and his wife Elizabeth farmed the land and had eight children, the youngest of whom was the first boy, named Welcome. But he died in infancy. In 19th-century Ohio, farmers had lots of children, always hoping for sons to help with farming and eventually to assume ownership. To lose the only son must have been hard on them. Perhaps his loss was just as difficult as the seven sisters experienced living in a small three-bedroom farmhouse with their parents – one room for the parents and two for the girls. Seven of them in two bedrooms. Imagine that! Pioneer women were tough.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Kay Lamb, current owner of this 150-acre farm, explained that Joseph Kester, a traveling Lutheran minister as well as a master carpenter, built the 1850-era farmhouse where her nephew David now lives. Kester may have built a barn at the time, but it didn’t last. In 1880 the Retterer family took over the farm and David Retterer built the present barn in 1886.

He and his wife Elizabeth farmed the land and had eight children, the youngest of whom was the first boy, named Welcome. But he died in infancy. In 19th-century Ohio, farmers had lots of children, always hoping for sons to help with farming and eventually to assume ownership. To lose the only son must have been hard on them. Perhaps his loss was just as difficult as the seven sisters experienced living in a small three-bedroom farmhouse with their parents – one room for the parents and two for the girls. Seven of them in two bedrooms. Imagine that! Pioneer women were tough.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MEDINA

“Longview Acres”

As I drove south from Lorain County and through the northern part of Medina County, I was enthralled by the number of outstanding old barns that I passed, making me hope that I’d be invited back for a full barn tour someday. David Schmidt, a young man with a passion about his old barn read about me in the Ohio Country Journal and invited me to visit. I was glad to meet someone so young with such an interest in Ohio antiquity.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

As I drove south from Lorain County and through the northern part of Medina County, I was enthralled by the number of outstanding old barns that I passed, making me hope that I’d be invited back for a full barn tour someday. David Schmidt, a young man with a passion about his old barn read about me in the Ohio Country Journal and invited me to visit. I was glad to meet someone so young with such an interest in Ohio antiquity.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MEIGS

“Presidential”

Courtney Midkiff, daughter of barn owner Cecil Midkiff, contacted me after reading an article about my barn project in the Pomeroy Sentinel newspaper. She wrote that her family has owned the farm since 1822, making them eligible to become a rare Ohio bicentennial farm in a few years.

After negotiating the twisting roads of Morgan and Athens counties, pushing me behind schedule, I finally arrived at the simple English threshing barn, one used for hay storage and dairy cattle. The family leases out 75 of the 140 acres for hay and corn, some of whose orange and ochre-colored stalks added to the painting’s composition, as did the rustic barn siding, which Cecil supplied for the frame.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Courtney Midkiff, daughter of barn owner Cecil Midkiff, contacted me after reading an article about my barn project in the Pomeroy Sentinel newspaper. She wrote that her family has owned the farm since 1822, making them eligible to become a rare Ohio bicentennial farm in a few years.

After negotiating the twisting roads of Morgan and Athens counties, pushing me behind schedule, I finally arrived at the simple English threshing barn, one used for hay storage and dairy cattle. The family leases out 75 of the 140 acres for hay and corn, some of whose orange and ochre-colored stalks added to the painting’s composition, as did the rustic barn siding, which Cecil supplied for the frame.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MERCER

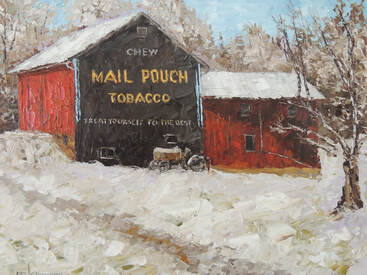

“Winter’s First Blast”

After delivering Darke County barn paintings to Jenny at the Garst Museum in Greenville early on a November morning, I headed north on Route 127, hoping to find a barn in four counties – Mercer, Van Wert, Paulding, and Defiance. It was dawn but there was no sun. Just a blizzard. By the time I crossed the county line into Mercer County, the snow intensified, almost to white-out level. Fortunately, the ground was still warm so that the roads remained clear, but visibility was not good. In hindsight, I suppose I was lucky to spot this complex of an old brick farmhouse and a barn with three cupolas – since the snow blotted out much of the details. I did a sketch, took photos, and hoped that I’d find some information about this old beauty, not far from Coldwater, a town appropriately named, and one, I remembered, where one of my dental school classmates practiced. I looked up his practice and called the dentists who took over, hoping to shed some light on this barn’s story.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

After delivering Darke County barn paintings to Jenny at the Garst Museum in Greenville early on a November morning, I headed north on Route 127, hoping to find a barn in four counties – Mercer, Van Wert, Paulding, and Defiance. It was dawn but there was no sun. Just a blizzard. By the time I crossed the county line into Mercer County, the snow intensified, almost to white-out level. Fortunately, the ground was still warm so that the roads remained clear, but visibility was not good. In hindsight, I suppose I was lucky to spot this complex of an old brick farmhouse and a barn with three cupolas – since the snow blotted out much of the details. I did a sketch, took photos, and hoped that I’d find some information about this old beauty, not far from Coldwater, a town appropriately named, and one, I remembered, where one of my dental school classmates practiced. I looked up his practice and called the dentists who took over, hoping to shed some light on this barn’s story.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MIAMI

“Colonel Johnston’s”

There’s a lot to see at the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency, located in Piqua, Ohio, right off I-75, north of Dayton. One of Ohio’s historical gems, the farm features a spring house, a cider house, an 1815 federal brick farmhouse, an Adena Indian earthwork and mound, a canal boat and the chance to ride on it, and, of course, the barn, a rare log double-pen barn, one of few left in Ohio and probably one of Ohio’s first ones, built in 1808. Throughout the year, the farm plans activities for the entire family, ranging from re-enactors portraying early Ohio history to a relaxing ride on the General Harrison on the Miami and Erie Canal.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

There’s a lot to see at the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency, located in Piqua, Ohio, right off I-75, north of Dayton. One of Ohio’s historical gems, the farm features a spring house, a cider house, an 1815 federal brick farmhouse, an Adena Indian earthwork and mound, a canal boat and the chance to ride on it, and, of course, the barn, a rare log double-pen barn, one of few left in Ohio and probably one of Ohio’s first ones, built in 1808. Throughout the year, the farm plans activities for the entire family, ranging from re-enactors portraying early Ohio history to a relaxing ride on the General Harrison on the Miami and Erie Canal.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MONROE

"Kindelberger New"

Thanks to its gracious owners, this barn, one of Ohio's best and honored by being listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is preserved not only in this painting but also in its own wood. Its intriguing story begins with 11-year-old Frederick Kindelberger, Jr., who moved here with his parents from Bavaria in 1835. He started building this stone barn in 1883, quarrying sandstone from the farm. The story is spiced with plenty of German ingenuity ... and hard work.

And, they now offer hospitality in a wonderful rustic rental cabin, which gives this view of the barns. When I stayed in it for two nights during a fundraiser event in October, 2021, it reminded me of the lodge in Yellowstone. Hard to find, but it's worth it! Click here for info on the cabin.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Thanks to its gracious owners, this barn, one of Ohio's best and honored by being listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is preserved not only in this painting but also in its own wood. Its intriguing story begins with 11-year-old Frederick Kindelberger, Jr., who moved here with his parents from Bavaria in 1835. He started building this stone barn in 1883, quarrying sandstone from the farm. The story is spiced with plenty of German ingenuity ... and hard work.

And, they now offer hospitality in a wonderful rustic rental cabin, which gives this view of the barns. When I stayed in it for two nights during a fundraiser event in October, 2021, it reminded me of the lodge in Yellowstone. Hard to find, but it's worth it! Click here for info on the cabin.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Kindelberger Old”

It would not be fair to paint Kindelberger’s stone barn, nationally recognized, and ignore the original, a barn that sits quietly in the shadows of the famous one but still manages to exude rustic charm. As I wrote about the famous 1883 stone barn, barns and farms that pass from one or two generations are fairly common, but one that has passed to the fifth generation – Marge Baumberger – qualifies as unique. Click here for the rest of this story.

It would not be fair to paint Kindelberger’s stone barn, nationally recognized, and ignore the original, a barn that sits quietly in the shadows of the famous one but still manages to exude rustic charm. As I wrote about the famous 1883 stone barn, barns and farms that pass from one or two generations are fairly common, but one that has passed to the fifth generation – Marge Baumberger – qualifies as unique. Click here for the rest of this story.

MONTGOMERY

“The Medic”

I missed seeing the small Christmas Tree farm sign on Route 35 – west of Dayton – and sped by it, turned around, and apparently pulled back onto the road too slowly as an angry car horn announced. As I entered, the farm looked like a scene from the Barn Builders show, a popular series on the DIY network: a tall red crane was lifting a long hand-hewn-timber beam, positioning it, while several workers were drilling, cutting, and shaping other lumber. The Renchs, Laura and David, had hired a timber framer to restore an 1816 barn from across the street. Noble souls. Historical preservationists, just like me.

They also own another early 19th century barn, which they used as an office for the Christmas tree farm they used to operate. And a third “newer” one, built in 1903, serves as storage, a good place for old barn wood, allowing me to choose and pick for framing this painting.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

I missed seeing the small Christmas Tree farm sign on Route 35 – west of Dayton – and sped by it, turned around, and apparently pulled back onto the road too slowly as an angry car horn announced. As I entered, the farm looked like a scene from the Barn Builders show, a popular series on the DIY network: a tall red crane was lifting a long hand-hewn-timber beam, positioning it, while several workers were drilling, cutting, and shaping other lumber. The Renchs, Laura and David, had hired a timber framer to restore an 1816 barn from across the street. Noble souls. Historical preservationists, just like me.

They also own another early 19th century barn, which they used as an office for the Christmas tree farm they used to operate. And a third “newer” one, built in 1903, serves as storage, a good place for old barn wood, allowing me to choose and pick for framing this painting.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MORGAN

“The Snake Killer”

Driving through Morgan County, a good sampling of Ohio’s Appalachia, was the most adventurous expedition I had taken, topping even the supremely hilly Monroe County. County Road 91, a dirt and gravel road, barely wide enough for two cars, full of hairpin turns, steep drop offs, and woods mimicking a national forest, stretched for three miles. Fortunately, no other cars challenged me on this early morning in September.

But the arduous journey was worth it: the Farnsworth barn was a gem. After going down Richardson Lane, a private drive named after the family, and then up a steep hill, making me wonder how anyone could farm here, I arrived at the 1836-built farmhouse, where I met Claire Richardson Farnsworth, her daughter Grace, and her son-in-law Jim Gregg. After a chat, we drove down the hill and then up another one to look at the barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Driving through Morgan County, a good sampling of Ohio’s Appalachia, was the most adventurous expedition I had taken, topping even the supremely hilly Monroe County. County Road 91, a dirt and gravel road, barely wide enough for two cars, full of hairpin turns, steep drop offs, and woods mimicking a national forest, stretched for three miles. Fortunately, no other cars challenged me on this early morning in September.

But the arduous journey was worth it: the Farnsworth barn was a gem. After going down Richardson Lane, a private drive named after the family, and then up a steep hill, making me wonder how anyone could farm here, I arrived at the 1836-built farmhouse, where I met Claire Richardson Farnsworth, her daughter Grace, and her son-in-law Jim Gregg. After a chat, we drove down the hill and then up another one to look at the barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MORROW

"Hole-in-the-Wall Gang"

The Hole in the Wall is a remote pass in the Big Horn Mountains in Johnson County, Wyoming, where a group of cattle rustlers, known as the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang would hide. In the late 19th century this gang and Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch stayed here at a log cabin, built in 1883, which is now preserved at the Old Trail Town museum in Cody, Wyoming. Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, remembered in the movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, eluded lawmen for years in this hideout, which was used by many outlaws from the 1860s to 1910, when it faded away into history.

Actor Paul Newman, an Ohio native, founded a summer camp for children with serious illnesses in Connecticut in 1987. He called it the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp, which quickly grew into an organization called the Serious Fun Children’s Network, individually financed and operated camps, which have served hundreds of thousands of children worldwide. Newman believed that children facing such terrible diseases should have a “hideout,” which his camp provided.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

The Hole in the Wall is a remote pass in the Big Horn Mountains in Johnson County, Wyoming, where a group of cattle rustlers, known as the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang would hide. In the late 19th century this gang and Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch stayed here at a log cabin, built in 1883, which is now preserved at the Old Trail Town museum in Cody, Wyoming. Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, remembered in the movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, eluded lawmen for years in this hideout, which was used by many outlaws from the 1860s to 1910, when it faded away into history.

Actor Paul Newman, an Ohio native, founded a summer camp for children with serious illnesses in Connecticut in 1987. He called it the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp, which quickly grew into an organization called the Serious Fun Children’s Network, individually financed and operated camps, which have served hundreds of thousands of children worldwide. Newman believed that children facing such terrible diseases should have a “hideout,” which his camp provided.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

MUSKINGUM

“Pristine”

Dawn was beginning to break, its early morning glow casting shadows and highlighting hay bales in the field, as I approached this old barn, which sits on a ridge overlooking acres the McDonald farm. Even though I had spent most of the previous day in a whirlwind tour of Ohio’s eastern counties – an adventurous drive through a curvy slice of the Appalachian Plateau – I felt refreshed after a night of sleep in a Zanesville hotel. I was ready for more barns – this one and the famous three round barns of neighboring Perry County. The chamber of commerce kindly referred me to Susan McDonald, a local attorney and farmer, whose family roots trace back to 1858 when Samuel Culbertson established the farm, along with a store and a post office. During the Civil War, according to the family, Confederate General John Hunt Morgan passed by here on his raid into Ohio, though this time he paid for provisions – after noticing a Free Mason sign on the property. Shades of one of my favorite movies, A Man Who Would Be King.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Dawn was beginning to break, its early morning glow casting shadows and highlighting hay bales in the field, as I approached this old barn, which sits on a ridge overlooking acres the McDonald farm. Even though I had spent most of the previous day in a whirlwind tour of Ohio’s eastern counties – an adventurous drive through a curvy slice of the Appalachian Plateau – I felt refreshed after a night of sleep in a Zanesville hotel. I was ready for more barns – this one and the famous three round barns of neighboring Perry County. The chamber of commerce kindly referred me to Susan McDonald, a local attorney and farmer, whose family roots trace back to 1858 when Samuel Culbertson established the farm, along with a store and a post office. During the Civil War, according to the family, Confederate General John Hunt Morgan passed by here on his raid into Ohio, though this time he paid for provisions – after noticing a Free Mason sign on the property. Shades of one of my favorite movies, A Man Who Would Be King.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

NOBLE

“Junior and the Nuns”

On my September, 2018, tour of Ohio’s eastern counties I hoped to find a barn in the little section of Noble County I’d be going through and, since the historical society didn’t respond to my query, I’d have to find it on my own. Fortunately I found one, a nice blue barn just off Route 78. And the bonus was that Leianne, my Summit County historical guru who grew up in this county, knew about it.

The road sign, which I opted to leave out of the painting, read “Woodfield Rd.” and “Zwick Rd.,” the latter leading towards the barn and farmhouse. Leianne told me that the farm was owned for a long time by “Junior” and his wife and that the Zwick family still owns it.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

On my September, 2018, tour of Ohio’s eastern counties I hoped to find a barn in the little section of Noble County I’d be going through and, since the historical society didn’t respond to my query, I’d have to find it on my own. Fortunately I found one, a nice blue barn just off Route 78. And the bonus was that Leianne, my Summit County historical guru who grew up in this county, knew about it.

The road sign, which I opted to leave out of the painting, read “Woodfield Rd.” and “Zwick Rd.,” the latter leading towards the barn and farmhouse. Leianne told me that the farm was owned for a long time by “Junior” and his wife and that the Zwick family still owns it.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“A Noble Surprise”

Every now and then, something totally unexpected happens during a barn tour. Taking notes from the last barn we visited, I wasn’t paying attention as barn scout Jeff drove his vintage Chevrolet, manufactured during the Great Depression, sputtering down a twisting gravel road. He said calmly, “Bob, it would be interesting if my car died right – since we probably don’t have cell phone service here. This is pretty remote.” I had to agree. Just then he stopped – on purpose, though.

Across from us sat a small gray barn, not much to look at – obviously in poor condition and getting worse day by day. The roof of the add-on on its left side had completely collapsed. The ancient metal corn crib – with a ladder reaching the top – had rusted. One of the barn doors had fallen off and two more were barely hanging on to their hinges. It was a mess.

But then came the surprise. As we glanced inside, there, standing securely, was an original log barn, about 20 by 20 feet, its logs still intact, 11 beams high in a square. One beam, near where the floor had been, had a series of mortise cuts, where beams used to connect with tenons and wooden pegs. Though the floor was missing, showing the lower level, where a few animals might have been housed, the structure was remarkably sound. However, there was no chinking, which is the process of closing the gaps between the logs, first by an assortment of fillers – corn cobs, manure, straw – and then an application of mud or cement for the outer layer. The corner notches were basic, nothing elaborate – simply V-shaped edges that allowed the logs to sit on one another – sort of like the Roman aqueducts, built with stone blocks without cement, still standing after 2,000 years.

Over the years, the farmer needed more room, which led to his adding to both sides of the log barn. Ironically these newer additions are deteriorating, while the original logs are still in great shape. Someone added a metal roof, which is why these beams have not rotted. Of course, they might be white oak, which is tough as steel and insect resistant. No signs of bugs anywhere on these logs.

This an extremely rare Ohio barn and may be the oldest building in Noble County and, as such, deserves to be preserved. Yes, there are many log cabins still preserved in the state, but very few log barns. In fact, it may date to earlier than 1810, though dendrochronology could accurately pin point the year that the logs were harvested. Thanks to Jeff and his taking me along the back roads, this gem has been discovered, a wonderful surprise in Noble County. Now, will it be preserved?

Every now and then, something totally unexpected happens during a barn tour. Taking notes from the last barn we visited, I wasn’t paying attention as barn scout Jeff drove his vintage Chevrolet, manufactured during the Great Depression, sputtering down a twisting gravel road. He said calmly, “Bob, it would be interesting if my car died right – since we probably don’t have cell phone service here. This is pretty remote.” I had to agree. Just then he stopped – on purpose, though.

Across from us sat a small gray barn, not much to look at – obviously in poor condition and getting worse day by day. The roof of the add-on on its left side had completely collapsed. The ancient metal corn crib – with a ladder reaching the top – had rusted. One of the barn doors had fallen off and two more were barely hanging on to their hinges. It was a mess.

But then came the surprise. As we glanced inside, there, standing securely, was an original log barn, about 20 by 20 feet, its logs still intact, 11 beams high in a square. One beam, near where the floor had been, had a series of mortise cuts, where beams used to connect with tenons and wooden pegs. Though the floor was missing, showing the lower level, where a few animals might have been housed, the structure was remarkably sound. However, there was no chinking, which is the process of closing the gaps between the logs, first by an assortment of fillers – corn cobs, manure, straw – and then an application of mud or cement for the outer layer. The corner notches were basic, nothing elaborate – simply V-shaped edges that allowed the logs to sit on one another – sort of like the Roman aqueducts, built with stone blocks without cement, still standing after 2,000 years.

Over the years, the farmer needed more room, which led to his adding to both sides of the log barn. Ironically these newer additions are deteriorating, while the original logs are still in great shape. Someone added a metal roof, which is why these beams have not rotted. Of course, they might be white oak, which is tough as steel and insect resistant. No signs of bugs anywhere on these logs.

This an extremely rare Ohio barn and may be the oldest building in Noble County and, as such, deserves to be preserved. Yes, there are many log cabins still preserved in the state, but very few log barns. In fact, it may date to earlier than 1810, though dendrochronology could accurately pin point the year that the logs were harvested. Thanks to Jeff and his taking me along the back roads, this gem has been discovered, a wonderful surprise in Noble County. Now, will it be preserved?

“The Trustee”