OHIO

ALLEN

“Rozell’s Round”

Less than two dozen round or circular-sided (hexagonal, octagonal, etc.) barns remain in Ohio, though hundreds of them dot neighboring states – Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin. This is one of them and it’s one of the reasons that drew me to Allen County. It’s owned by Donald Montooth and his wife Darlene, whose great-grandfather came here from Wales. The barn is located in Elida.

When barn scout Rheuben and I visited Mr. Montooth, he told us that he’s originally from Fort Wayne, Indiana and that, although he spent his career in working for a gas company, he always wanted to own a farm. In 1965 his dream came true when he bought this farm, originally 50 acres, and home to one of Ohio’s gems, a round bank barn. Donald raised horses, corn, soybeans, and hay, though he now retains only 11 of the 50 acres. A newly-painted white fence surrounds his horses and his barn overlooks them. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

The original owner, Lewis Feightner, hired Isaac Rozell in 1911 to construct this round barn. He, in turn, hired Eli Meyers as the builder. A century later, it’s still in good shape. It’s been painted over the years and it’s had two new roofs since Mr. Montooth has owned it. The brown gambrel domed roof contrasts nicely with the white siding and its round cupola adds another dimension to the composition. Its interior, always a joy to behold in a round barn, features a central tall wooden silo and original rafters radiating from the ceiling, like spokes on a bicycle. A basketball hoop, its net, and a wooden backboard prove that, at one time, young athletes worked on their game in this barn … in between farm chores, that is.

Congratulations to Donald Montooth for preserving and maintaining this Ohio treasure. Hopefully it will stand for many more years, testifying to the carpentry skills of the early Ohioans.

Less than two dozen round or circular-sided (hexagonal, octagonal, etc.) barns remain in Ohio, though hundreds of them dot neighboring states – Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin. This is one of them and it’s one of the reasons that drew me to Allen County. It’s owned by Donald Montooth and his wife Darlene, whose great-grandfather came here from Wales. The barn is located in Elida.

When barn scout Rheuben and I visited Mr. Montooth, he told us that he’s originally from Fort Wayne, Indiana and that, although he spent his career in working for a gas company, he always wanted to own a farm. In 1965 his dream came true when he bought this farm, originally 50 acres, and home to one of Ohio’s gems, a round bank barn. Donald raised horses, corn, soybeans, and hay, though he now retains only 11 of the 50 acres. A newly-painted white fence surrounds his horses and his barn overlooks them. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

The original owner, Lewis Feightner, hired Isaac Rozell in 1911 to construct this round barn. He, in turn, hired Eli Meyers as the builder. A century later, it’s still in good shape. It’s been painted over the years and it’s had two new roofs since Mr. Montooth has owned it. The brown gambrel domed roof contrasts nicely with the white siding and its round cupola adds another dimension to the composition. Its interior, always a joy to behold in a round barn, features a central tall wooden silo and original rafters radiating from the ceiling, like spokes on a bicycle. A basketball hoop, its net, and a wooden backboard prove that, at one time, young athletes worked on their game in this barn … in between farm chores, that is.

Congratulations to Donald Montooth for preserving and maintaining this Ohio treasure. Hopefully it will stand for many more years, testifying to the carpentry skills of the early Ohioans.

ASHTABULA

“The Octagonal”

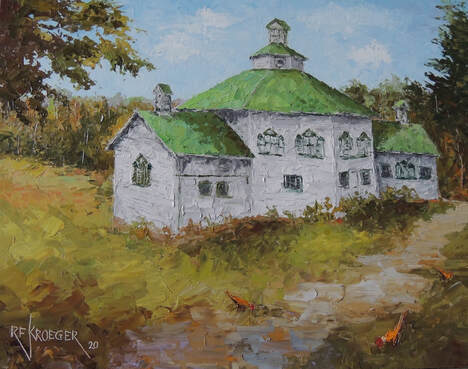

I visited this weathered gray octagonal barn in 2014 with Carl Feather and Jeff Scribben, barn enthusiasts in Ashtabula County, on a day when the orange day lilies in front and alongside the barn were at their best, almost begging for photos. Although we didn’t meet the barn owner, we talked with a lady whose husband rents the farm from his father. They do organic gardening on 100 acres. She agreed that the barn was special. In fact, it’s the only surviving octagonal barn in northeast Ohio.

Local legend dates the barn to 1865 – four years after the brick barn at Nutwood Place, giving credit to a Mr. Dewey for building it. The story goes that the owner imported blue glass from Belgium for the windows, with the hope that the glass would make the hay look green (Of course, it dries to a beige color after harvesting and being stored in the barn), thereby encouraging cows to eat it. I don’t know whose idea that was, but maybe it worked. Another theory is that the blue glass could have lessened the intensity of sunlight and helped prevent a barn fire. Several panes still show blue glass, which was used over clear glass, which often had bubbles in it, a manufacturing defect. The bubbles could focus the sunlight – as a lens does – onto hay and ignite a fire. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THE STORY

I visited this weathered gray octagonal barn in 2014 with Carl Feather and Jeff Scribben, barn enthusiasts in Ashtabula County, on a day when the orange day lilies in front and alongside the barn were at their best, almost begging for photos. Although we didn’t meet the barn owner, we talked with a lady whose husband rents the farm from his father. They do organic gardening on 100 acres. She agreed that the barn was special. In fact, it’s the only surviving octagonal barn in northeast Ohio.

Local legend dates the barn to 1865 – four years after the brick barn at Nutwood Place, giving credit to a Mr. Dewey for building it. The story goes that the owner imported blue glass from Belgium for the windows, with the hope that the glass would make the hay look green (Of course, it dries to a beige color after harvesting and being stored in the barn), thereby encouraging cows to eat it. I don’t know whose idea that was, but maybe it worked. Another theory is that the blue glass could have lessened the intensity of sunlight and helped prevent a barn fire. Several panes still show blue glass, which was used over clear glass, which often had bubbles in it, a manufacturing defect. The bubbles could focus the sunlight – as a lens does – onto hay and ignite a fire. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THE STORY

AUGLAIZE

“Magnificent Manchester”

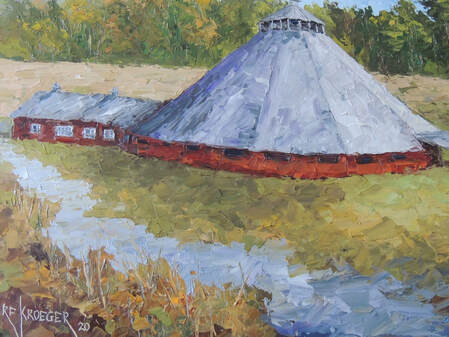

This iconic round barn is one of Ohio’s most photographed and painted, and rightfully so. The dark roof, contrasting with deep red siding and white trim, provides a striking composition, which many artists have been drawn to capture, as evidenced by the hundreds of images found in a Google search.

Even though George Washington designed and built a sixteen-sided threshing barn at his farm in Virginia in 1793 and the Shakers built the first truly round barn in Massachusetts in 1826, this type of barn did not catch on until the late 1800s. An article, The Economy of a Round Dairy Barn, written by Wilbur Frazer and published by the University of Illinois in 1908, described the benefits of a round barn: more efficient housing for cows, time savings in feeding, a protected silo, and easier silage distribution. The article also inferred that construction of a round barn was less expensive than a rectangular one and that “progressive” farmers should consider such a barn. The opposite was true – circular barns were more expensive than rectangular ones and the “progressive” farmers were usually only the wealthy ones.

CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY

This iconic round barn is one of Ohio’s most photographed and painted, and rightfully so. The dark roof, contrasting with deep red siding and white trim, provides a striking composition, which many artists have been drawn to capture, as evidenced by the hundreds of images found in a Google search.

Even though George Washington designed and built a sixteen-sided threshing barn at his farm in Virginia in 1793 and the Shakers built the first truly round barn in Massachusetts in 1826, this type of barn did not catch on until the late 1800s. An article, The Economy of a Round Dairy Barn, written by Wilbur Frazer and published by the University of Illinois in 1908, described the benefits of a round barn: more efficient housing for cows, time savings in feeding, a protected silo, and easier silage distribution. The article also inferred that construction of a round barn was less expensive than a rectangular one and that “progressive” farmers should consider such a barn. The opposite was true – circular barns were more expensive than rectangular ones and the “progressive” farmers were usually only the wealthy ones.

CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY

CHAMPAIGN

“Nutwood”

Webster defines nutwood as any nutbearing tree or its wood. In 1815 when this farm’s history began, plenty of nutbearing trees dotted the Ohio landscape, such as chestnut, walnut, and hickory. Perhaps William Ward, the farm’s founder, named his farm, “Nutwood Place,” after such trees.

Ward, a native of Virginia, served as an officer in the Revolutionary War, and, both educated and business-saavy, he made the most of his and his father’s war service land grants. Moving to Maysville, Kentucky, he claimed land that had been axe marked by Simon Kenton, the legendary frontiersman, who, unfortunately basically illiterate, never bothered to register his claimed land. However, Ward and Kenton became business partners.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Webster defines nutwood as any nutbearing tree or its wood. In 1815 when this farm’s history began, plenty of nutbearing trees dotted the Ohio landscape, such as chestnut, walnut, and hickory. Perhaps William Ward, the farm’s founder, named his farm, “Nutwood Place,” after such trees.

Ward, a native of Virginia, served as an officer in the Revolutionary War, and, both educated and business-saavy, he made the most of his and his father’s war service land grants. Moving to Maysville, Kentucky, he claimed land that had been axe marked by Simon Kenton, the legendary frontiersman, who, unfortunately basically illiterate, never bothered to register his claimed land. However, Ward and Kenton became business partners.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

CLARK

“Rarest of the Rare”

This octagonal stone barn is almost one of a kind. In fact, I had to search far and wide before I found another – the Gilmore barn in Missouri, a three-story limestone octagonal bank barn, built in 1899. Restored smartly, it serves as an event center for the community. In 1994 it made the National Register of Historic Places.

I couldn’t find any stone octagonal barns in Ohio. Yes, Ohio has round and polygonal barns, but they’re wooden. One exception is Champaign County’s Nutwood, which is brick. So, I was excited to find this one and to meet Bob McClure, son of the owner, Marjorie McClure. Fortunately for me, Bob took some time out of his farming schedule to show me not only his barn but several others close by, including a wooden octagonal. Ohio’s wet spring had delayed planting.

Mrs. McClure bought the barn in 2010 in a farm auction from Glenn Murphy, not because of the unique barn but because of the 64 tillable acres that came with it, ideal farm land. The stone barn was a bonus, but it was a mess. Bob told me that they filled 40 dumpsters with trash from the barn and disposed of 300 old tires in the clean-up. He also installed new shutters and a front door.

Bob didn’t know much about the history of the barn, though a local farmer, Joe Shank, owned it at one time, along with the wooden octagonal barn a few miles away. McClure’s barn was probably built around 1900 in a time when many polygonal barns were built, though much later than another Ohio icon, the octagonal brick one-room school house in Sinking Spring, Highland County, which was built in 1831.

Although most of the timber in the top level is saw-cut, hand-hewn beams, possibly reclaimed from an earlier barn, frame the front door. On the lower level, the major beams are hand-hewn and stalls for sheep remain intact. The octagonal cupola was in good shape and the stone work reminded me of the craftsmanship of the Kindelberger stone barn in Monroe County. Stone masons can leave their mark that withstands all kinds of weather. Overall, this barn, maintained well by the McClures, is not only an Ohio gem, but a national treasure and deserves a listing in the National Register of Historic Places. After all, it’s the rarest of the rare.

This octagonal stone barn is almost one of a kind. In fact, I had to search far and wide before I found another – the Gilmore barn in Missouri, a three-story limestone octagonal bank barn, built in 1899. Restored smartly, it serves as an event center for the community. In 1994 it made the National Register of Historic Places.

I couldn’t find any stone octagonal barns in Ohio. Yes, Ohio has round and polygonal barns, but they’re wooden. One exception is Champaign County’s Nutwood, which is brick. So, I was excited to find this one and to meet Bob McClure, son of the owner, Marjorie McClure. Fortunately for me, Bob took some time out of his farming schedule to show me not only his barn but several others close by, including a wooden octagonal. Ohio’s wet spring had delayed planting.

Mrs. McClure bought the barn in 2010 in a farm auction from Glenn Murphy, not because of the unique barn but because of the 64 tillable acres that came with it, ideal farm land. The stone barn was a bonus, but it was a mess. Bob told me that they filled 40 dumpsters with trash from the barn and disposed of 300 old tires in the clean-up. He also installed new shutters and a front door.

Bob didn’t know much about the history of the barn, though a local farmer, Joe Shank, owned it at one time, along with the wooden octagonal barn a few miles away. McClure’s barn was probably built around 1900 in a time when many polygonal barns were built, though much later than another Ohio icon, the octagonal brick one-room school house in Sinking Spring, Highland County, which was built in 1831.

Although most of the timber in the top level is saw-cut, hand-hewn beams, possibly reclaimed from an earlier barn, frame the front door. On the lower level, the major beams are hand-hewn and stalls for sheep remain intact. The octagonal cupola was in good shape and the stone work reminded me of the craftsmanship of the Kindelberger stone barn in Monroe County. Stone masons can leave their mark that withstands all kinds of weather. Overall, this barn, maintained well by the McClures, is not only an Ohio gem, but a national treasure and deserves a listing in the National Register of Historic Places. After all, it’s the rarest of the rare.

FAIRFIELD

“The County Fair”

Signage, above several entrances to this circular barn, clearly states its history: Round Cattle Barn – Built in 1906 – By J.E. Hedges – Dairy Cattle. It’s a rarity – a round barn built specifically for a county fair.

Hedges, a local farmer and barn builder, could have chosen a traditional rectangular barn for this project, but this was an era when round barns were considered ideal for dairy cattle. For his labor and materials Hedges was paid $3,022.14, a huge sum in 1906. He cleverly soaked the lumber for the curved section in a creek and then was able to bend it into a circle. The barn, built for dairy and beef cattle, also housed the junior livestock sale.

With a diameter stretching to 95 feet and a roof covered with wood shingles, the sight must have commanded attention during the county fair in 1906. Apparently local residents began to appreciate the uniqueness of the barn and so they covered the roof with galvanized metal in 1934, assuring longevity. In 1937, with the fair’s popularity growing – despite the throes of the Great Depression – they added two large wings to the round barn.

What’s just as impressive as the barn is the county fair, which dates to 1851, the oldest continuously running county fair in Ohio. In 1850 the Fairfield County Agricultural Society formed and hosted the fair in Lancaster the following year. Only 60 years earlier Lancaster, the county seat, was comprised of 100 wigwams and 500 people. The fertile fields drew immigrants and agriculture was king. Indians moved westwards.

In 1876 the fairgrounds expanded to 22 acres and again to 36 acres in 1880, when a half-mile race track was added. Three years later organizers built a new amphitheatre and eventually drilled for natural gas. In 1889 they found it, tapping its energy to provide light for night-time races, the only place in America that offered night racing. They also piped the gas to the center of a lake in the fairgrounds and ignited it as it bubbled up through perforated pipes, earning the title, “Lake of Fire.” What a sight that must have been!

Another feather on this barn’s cap was that it was used in filming the 1980 movie, Brubaker, starring Robert Redford. Chances are that the film crew didn’t know much about J.E. Hedges but they liked his barn well enough to use it. I’m sure, if he were alive, he’d be proud.

Signage, above several entrances to this circular barn, clearly states its history: Round Cattle Barn – Built in 1906 – By J.E. Hedges – Dairy Cattle. It’s a rarity – a round barn built specifically for a county fair.

Hedges, a local farmer and barn builder, could have chosen a traditional rectangular barn for this project, but this was an era when round barns were considered ideal for dairy cattle. For his labor and materials Hedges was paid $3,022.14, a huge sum in 1906. He cleverly soaked the lumber for the curved section in a creek and then was able to bend it into a circle. The barn, built for dairy and beef cattle, also housed the junior livestock sale.

With a diameter stretching to 95 feet and a roof covered with wood shingles, the sight must have commanded attention during the county fair in 1906. Apparently local residents began to appreciate the uniqueness of the barn and so they covered the roof with galvanized metal in 1934, assuring longevity. In 1937, with the fair’s popularity growing – despite the throes of the Great Depression – they added two large wings to the round barn.

What’s just as impressive as the barn is the county fair, which dates to 1851, the oldest continuously running county fair in Ohio. In 1850 the Fairfield County Agricultural Society formed and hosted the fair in Lancaster the following year. Only 60 years earlier Lancaster, the county seat, was comprised of 100 wigwams and 500 people. The fertile fields drew immigrants and agriculture was king. Indians moved westwards.

In 1876 the fairgrounds expanded to 22 acres and again to 36 acres in 1880, when a half-mile race track was added. Three years later organizers built a new amphitheatre and eventually drilled for natural gas. In 1889 they found it, tapping its energy to provide light for night-time races, the only place in America that offered night racing. They also piped the gas to the center of a lake in the fairgrounds and ignited it as it bubbled up through perforated pipes, earning the title, “Lake of Fire.” What a sight that must have been!

Another feather on this barn’s cap was that it was used in filming the 1980 movie, Brubaker, starring Robert Redford. Chances are that the film crew didn’t know much about J.E. Hedges but they liked his barn well enough to use it. I’m sure, if he were alive, he’d be proud.

HARRISON

“Workley’s Wonder”

The Harrison County visitor center thinks enough of this round barn to put its striking photo in its brochures as well as in those of other Ohio’s counties. Originally, I discovered it in the Dale Travis Ohio round building website. It’s been on my bucket list for years. But it’s not easy to find. Fortunately the historical society gave me the contact information of the barn’s owners, Judy and Ollie Workley, whom I called. Judy, 78, had just celebrated 61 years of marriage to Ollie, who, she said, also made picture frames out of barn wood. They were interested.

Nearer to my visit in September, 2018 – on my adventuresome barn hunting trip down the eastern Ohio Appalachian Plateau, a section of Ohio where a straight road is rare – Judy told me not to follow my GPS, which would lead me up a nasty gravel road. Thanks to her, I successfully found Skullfork Road, navigated the hills and forests, and arrived safely, emerging from the woods and smiling when I saw the bright red barn perched upon a hill, like a lighthouse beacon shining in the sea. It was stunning.

I met Judy, Ollie, and their daughter Tracy, who was visiting from Cleveland. Soon after my visit, they’d be going to the annual Barnesville pumpkin festival. I’m glad I got there before they left. The barn was worth it.

According to Judy, the original owner, John B. Steward, built the house and barn in 1921. His two sons fought in WWI and presumably helped their dad farm the hilly land. Over the years, unfortunately, the farm fell on hard times and had deteriorated by the time when the Workleys bought it in 1971. Thankfully, they felt so strongly about preserving Ohio history that they began to restore the barn, even adding a fresh coat of red paint recently. I loved the matching mailbox.

Actually, the barn is not round; it’s 16-sided and, as Judy proudly proclaimed, it’s the only 16-sided barn in Ohio. Each side is 12 feet long, the barn is 60 feet high, and it stretches 60 feet wide. Its sandstone foundation, quarried on the farm, reminded me of the Kindleberger stone barn in nearby Monroe County. The attractive cupola sits on top of a round silo, which, according to Judy, was filled only once. Removing the corn took too long.

Judy and Ollie raised cattle, horses, but mostly pigs – at one time 186 of the little fellows. Over the years, they’ve maintained the barn well – as shown by its new roof. Judy also added a flair of her own by painting old car tires red, gold, and violet and attaching them to fence posts leading to the barn. I had to include her art into the painting.

Although this barn is hard to find – virtually hidden in Appalachian woodland – it stands as a tribute not only to its builder of a century ago but also to the current owners who’ve been faithful stewards of Ohio history. Hopefully it will continue to survive as a reminder of Ohio’s early days, something that this essay and painting – framed in the barn’s own wood – also hope to accomplish.

The Harrison County visitor center thinks enough of this round barn to put its striking photo in its brochures as well as in those of other Ohio’s counties. Originally, I discovered it in the Dale Travis Ohio round building website. It’s been on my bucket list for years. But it’s not easy to find. Fortunately the historical society gave me the contact information of the barn’s owners, Judy and Ollie Workley, whom I called. Judy, 78, had just celebrated 61 years of marriage to Ollie, who, she said, also made picture frames out of barn wood. They were interested.

Nearer to my visit in September, 2018 – on my adventuresome barn hunting trip down the eastern Ohio Appalachian Plateau, a section of Ohio where a straight road is rare – Judy told me not to follow my GPS, which would lead me up a nasty gravel road. Thanks to her, I successfully found Skullfork Road, navigated the hills and forests, and arrived safely, emerging from the woods and smiling when I saw the bright red barn perched upon a hill, like a lighthouse beacon shining in the sea. It was stunning.

I met Judy, Ollie, and their daughter Tracy, who was visiting from Cleveland. Soon after my visit, they’d be going to the annual Barnesville pumpkin festival. I’m glad I got there before they left. The barn was worth it.

According to Judy, the original owner, John B. Steward, built the house and barn in 1921. His two sons fought in WWI and presumably helped their dad farm the hilly land. Over the years, unfortunately, the farm fell on hard times and had deteriorated by the time when the Workleys bought it in 1971. Thankfully, they felt so strongly about preserving Ohio history that they began to restore the barn, even adding a fresh coat of red paint recently. I loved the matching mailbox.

Actually, the barn is not round; it’s 16-sided and, as Judy proudly proclaimed, it’s the only 16-sided barn in Ohio. Each side is 12 feet long, the barn is 60 feet high, and it stretches 60 feet wide. Its sandstone foundation, quarried on the farm, reminded me of the Kindleberger stone barn in nearby Monroe County. The attractive cupola sits on top of a round silo, which, according to Judy, was filled only once. Removing the corn took too long.

Judy and Ollie raised cattle, horses, but mostly pigs – at one time 186 of the little fellows. Over the years, they’ve maintained the barn well – as shown by its new roof. Judy also added a flair of her own by painting old car tires red, gold, and violet and attaching them to fence posts leading to the barn. I had to include her art into the painting.

Although this barn is hard to find – virtually hidden in Appalachian woodland – it stands as a tribute not only to its builder of a century ago but also to the current owners who’ve been faithful stewards of Ohio history. Hopefully it will continue to survive as a reminder of Ohio’s early days, something that this essay and painting – framed in the barn’s own wood – also hope to accomplish.

MIAMI

“Orrmont”

Janelle and Tim Baker, who grew up in West Milton, an old Ohio village about 25 miles away, decided they’d move and, since they both enjoyed restoring old houses, bought the Orrmont Estate in 2003. Even though the 9,000-square-foot mansion, carriage house, and other buildings had once entertained the high and mighty, the grounds had not been maintained over the years. The Bakers had their work cut out for them.

They quickly filled in the pool with a cement base and erected a large tent which they rented for weddings and events, helping to offset the restoration expense. Then they began building a family, which now includes four sons, who continue to learn valuable lessons about entrepreneurship from their parents. Janelle, who grew up on a farm, became concerned about the possible loss of their parking lot and visualized the old octagonal barn nearby as another commercial asset. So, in 2012 they added the barn and 15 acres to their holdings, which again meant more rehabbing. CLICK HERE FOR THE STORY

Janelle and Tim Baker, who grew up in West Milton, an old Ohio village about 25 miles away, decided they’d move and, since they both enjoyed restoring old houses, bought the Orrmont Estate in 2003. Even though the 9,000-square-foot mansion, carriage house, and other buildings had once entertained the high and mighty, the grounds had not been maintained over the years. The Bakers had their work cut out for them.

They quickly filled in the pool with a cement base and erected a large tent which they rented for weddings and events, helping to offset the restoration expense. Then they began building a family, which now includes four sons, who continue to learn valuable lessons about entrepreneurship from their parents. Janelle, who grew up on a farm, became concerned about the possible loss of their parking lot and visualized the old octagonal barn nearby as another commercial asset. So, in 2012 they added the barn and 15 acres to their holdings, which again meant more rehabbing. CLICK HERE FOR THE STORY

“The Favorite”

After grandson Henry and I finished our visit to the Orrmont octagonal, we headed south, at the suggestion of Janelle, to see an octagonal barn owned by her neighbors – only about a mile away. Fortunately, we arrived just in time. Owner Ken Schauer was preparing to take his giant tractor out into the fields.

Though Ken said that his grandfather bought the farm in the 1980s, he didn’t know much about the barn’s history. Luckily, he allowed us to go inside, which often gives clues. One was that the iron bolting at the bents near the roof was identical to that in the Orrmont barn and the saw-cut lumber hinted at a construction date around 1900, also close to its neighbor. After William Orr built the Orrmont barn in the late 1890s, did he purchase this farm, hire the same carpenter, and build another octagonal? However, unlike its neighbor, this barn has a central concrete silo, though not in use. Outside, a giant silo towers over the barn.

In his website Dale Travis lists this farm as “The Favorite,” which may refer to the string of buildings, built by Mr. Orr in 1891 in downtown Piqua and known as the “Orr-Statler Block,” whose main tenant was a hotel, a massive building for its time – with more than 100 rooms. At first it was known as the “Plaza,” and later as the “Favorite.” Though the hotel closed in the 1980s, the city has restored the complex through a public-private renewal and the old building now hosts the public library and a restaurant. Just as this piece of history has been preserved, so has this octagonal barn, thanks to the Schauer’s covering its roof and sides with metal. I’ll bet that, out of all the farm buildings, it’s their favorite.

After grandson Henry and I finished our visit to the Orrmont octagonal, we headed south, at the suggestion of Janelle, to see an octagonal barn owned by her neighbors – only about a mile away. Fortunately, we arrived just in time. Owner Ken Schauer was preparing to take his giant tractor out into the fields.

Though Ken said that his grandfather bought the farm in the 1980s, he didn’t know much about the barn’s history. Luckily, he allowed us to go inside, which often gives clues. One was that the iron bolting at the bents near the roof was identical to that in the Orrmont barn and the saw-cut lumber hinted at a construction date around 1900, also close to its neighbor. After William Orr built the Orrmont barn in the late 1890s, did he purchase this farm, hire the same carpenter, and build another octagonal? However, unlike its neighbor, this barn has a central concrete silo, though not in use. Outside, a giant silo towers over the barn.

In his website Dale Travis lists this farm as “The Favorite,” which may refer to the string of buildings, built by Mr. Orr in 1891 in downtown Piqua and known as the “Orr-Statler Block,” whose main tenant was a hotel, a massive building for its time – with more than 100 rooms. At first it was known as the “Plaza,” and later as the “Favorite.” Though the hotel closed in the 1980s, the city has restored the complex through a public-private renewal and the old building now hosts the public library and a restaurant. Just as this piece of history has been preserved, so has this octagonal barn, thanks to the Schauer’s covering its roof and sides with metal. I’ll bet that, out of all the farm buildings, it’s their favorite.

PERRY

“The Round Barns of Perry County, Part I”

I was tired when I arrived in Perry County – after four days of barn touring, two painting demos, a fundraiser, and a tortuous drive through ten counties in eastern Ohio – but my hopes were high, thanks to the prospects of seeing one of the nation’s unique pockets of round barns. I had spent a few hours early on a September morning in driving through Muskingum County for a peek at Susan McDonald’s family barn, a quintessential composition at dawn. On the way out, I stumbled upon a rare covered bridge painted with the Mail Pouch logo, a delightful surprise.

Finally I arrived in Perry County and, going up a gravel road, managed with difficulty to find the first of four round barns, all located within a ten-mile radius, a rarity that’s almost a barn museum in itself. This, the first one I saw, belongs to Linda and Neil Cooperider. Neil’s great grandfather built the original barn in the late 1800s, but lost it to a fire. Neil’s grandparents took over the farm and its 270 acres around 1920. They built this barn around 1926. Now, it’s used for hay storage, which they use for beef cattle. They also raise corn.

Linda told me that the roof used to have a golden color, but, since it was deteriorating, they replaced it in 2018. Though she was gone when I visited, Neil was home and showed me the inside of the barn, always a treat to see since round barns are so unusual. A giant metal silo rises to the top – with hatch doors every six feet or so from bottom to top. Large hay bales were stacked next to the silo, proving that this beauty still functions.

While I did visit two other round barns, I didn’t venture to find the fourth, called the Dornbirer barn, which looked intriguing from a photo that I saw. The cupola, heavily fenestrated with windows, matched the roof, one side of which appeared to be collapsing. It might be gone by now.

I was tired when I arrived in Perry County – after four days of barn touring, two painting demos, a fundraiser, and a tortuous drive through ten counties in eastern Ohio – but my hopes were high, thanks to the prospects of seeing one of the nation’s unique pockets of round barns. I had spent a few hours early on a September morning in driving through Muskingum County for a peek at Susan McDonald’s family barn, a quintessential composition at dawn. On the way out, I stumbled upon a rare covered bridge painted with the Mail Pouch logo, a delightful surprise.

Finally I arrived in Perry County and, going up a gravel road, managed with difficulty to find the first of four round barns, all located within a ten-mile radius, a rarity that’s almost a barn museum in itself. This, the first one I saw, belongs to Linda and Neil Cooperider. Neil’s great grandfather built the original barn in the late 1800s, but lost it to a fire. Neil’s grandparents took over the farm and its 270 acres around 1920. They built this barn around 1926. Now, it’s used for hay storage, which they use for beef cattle. They also raise corn.

Linda told me that the roof used to have a golden color, but, since it was deteriorating, they replaced it in 2018. Though she was gone when I visited, Neil was home and showed me the inside of the barn, always a treat to see since round barns are so unusual. A giant metal silo rises to the top – with hatch doors every six feet or so from bottom to top. Large hay bales were stacked next to the silo, proving that this beauty still functions.

While I did visit two other round barns, I didn’t venture to find the fourth, called the Dornbirer barn, which looked intriguing from a photo that I saw. The cupola, heavily fenestrated with windows, matched the roof, one side of which appeared to be collapsing. It might be gone by now.

“The Round Barns of Perry County, Part II”

The second barn I visited, a bit easier to find, is owned by John and Judy McGaughey, who acquired it in 1965. Unfortunately, I could not wait until they returned from church and brunch in the early afternoon since my mental and physical batteries were low – with yet another barn to see and then a two-hour drive home.

Kim from the Perry Chamber of Commerce informed me that this originally was the Mott Thomas farm, though I don’t know when the farm was established nor if there was an older barn. Present-owner Judy told me that this barn was built in 1909, about the time when round barns had become popular, and that the owners used it as a dairy barn, which the round barn was famous for since it could hold more stanchions than a conventional barn of similar size. Today the family uses it for storage.

Its cupola needs help! Judy said that they can’t find a repair man to climb up the roof to fix the standing seam. Perhaps by now they’ve found someone to solve their problem. A leaky roof has been the final nail in many a barn’s coffin. Hopefully this iconic Ohio gem won’t face the same fate.

The second barn I visited, a bit easier to find, is owned by John and Judy McGaughey, who acquired it in 1965. Unfortunately, I could not wait until they returned from church and brunch in the early afternoon since my mental and physical batteries were low – with yet another barn to see and then a two-hour drive home.

Kim from the Perry Chamber of Commerce informed me that this originally was the Mott Thomas farm, though I don’t know when the farm was established nor if there was an older barn. Present-owner Judy told me that this barn was built in 1909, about the time when round barns had become popular, and that the owners used it as a dairy barn, which the round barn was famous for since it could hold more stanchions than a conventional barn of similar size. Today the family uses it for storage.

Its cupola needs help! Judy said that they can’t find a repair man to climb up the roof to fix the standing seam. Perhaps by now they’ve found someone to solve their problem. A leaky roof has been the final nail in many a barn’s coffin. Hopefully this iconic Ohio gem won’t face the same fate.

“The Round Barns of Perry County, Part III”

On my way out of the county I tried to find the third round barn but got lost, which happened fairly regularly in my solo expeditions. Tired, I thought momentarily about scratching it, but, in my compulsive need to finish projects, I turned around, meandered back and found it, hidden pretty well from the main road. Its ownership is still a mystery.

The chamber of commerce said that it’s owned by Robert Muetzel, but they didn’t have his phone number. Instead I sent snail mail to an address in Columbus, which the chamber also provided. Sadly the letter came back, undelivered – with the cryptic message, “unable to forward.”

The chamber reported that the barn was originally on a farm owned by the Gilmore family and that it was first built in 1917. After it burned, the family rebuilt it in 1932, during the somber days of the Great Depression. The farmers must have been successful enough to keep going, despite losing their barn, and must have loved the look of their round barn enough to build another one.

Unlike other round barns, the roof of this one is a perfectly round dome. From my viewpoint, even though I didn’t have the chance to go inside, it appears to be in great shape – as it stood impressively at the top of a field of grass, dominating the bucolic scene. Let’s hope whoever owns it has a sense of history and has the resources to maintain it. The three barns of Perry County may never have a movie made about them – as the bridges in Madison County did – but they serve as Ohio’s best trio of round barns. And that’s enough.

On my way out of the county I tried to find the third round barn but got lost, which happened fairly regularly in my solo expeditions. Tired, I thought momentarily about scratching it, but, in my compulsive need to finish projects, I turned around, meandered back and found it, hidden pretty well from the main road. Its ownership is still a mystery.

The chamber of commerce said that it’s owned by Robert Muetzel, but they didn’t have his phone number. Instead I sent snail mail to an address in Columbus, which the chamber also provided. Sadly the letter came back, undelivered – with the cryptic message, “unable to forward.”

The chamber reported that the barn was originally on a farm owned by the Gilmore family and that it was first built in 1917. After it burned, the family rebuilt it in 1932, during the somber days of the Great Depression. The farmers must have been successful enough to keep going, despite losing their barn, and must have loved the look of their round barn enough to build another one.

Unlike other round barns, the roof of this one is a perfectly round dome. From my viewpoint, even though I didn’t have the chance to go inside, it appears to be in great shape – as it stood impressively at the top of a field of grass, dominating the bucolic scene. Let’s hope whoever owns it has a sense of history and has the resources to maintain it. The three barns of Perry County may never have a movie made about them – as the bridges in Madison County did – but they serve as Ohio’s best trio of round barns. And that’s enough.

ROSS

“Marvelous Maxwell”

Sunshine Hill Farm, a small 15-acre corn and soybean farmstead, isn’t hard to miss when driving on State Route 180, just out of Kingston, thanks to this brilliant beacon of red and white, which can be seen for hundreds of yards in either direction. Its recent coat of fiery red paint and its twenty-eight-foot clerestory attract visitors, photographers, and artists: this true round barn is one of Ohio’s treasures. Peg Hays, sister of owner Chip Maxwell, emailed me and arranged our visit.

Using trees from adjacent woods – and a sawmill for cutting – Robert P. Maxwell, the family founder and great-grandfather of Chip and Peg, built the barn in 1910 and farmed 500 acres, keeping 100 head of beef cattle in the barn’s lower level. Over the years the farm passed down family lines until 1978 when three families divided up the 500 acres. Chip Maxwell and his wife Cherie were the lucky ones: they got the barn and eleven acres. But as the years passed by, a century of age caught up with the barn and the silo tilted, spelling impending doom.

According to a newspaper article, Cheri said, “You cannot put a price on sentimental value.” Yes, her husband Chip didn’t want to be on his deathbed, according to a newspaper article in the Chillicothe Gazette, Ohio’s oldest newspaper, founded in Cincinnati in 1793, knowing that he didn’t save the barn since his grandfather built it and his own dad cared so much for it. So he put his money where his sentiments were and paid a substantial sum to the Mt. Vernon Barn Company to save it. They uprighted the silo with cables and then stabilized the barn with new supports – mission accomplished. But, after such a costly restoration, what good is the barn? It doesn’t house crops or livestock. It’s just a beautiful old non-functioning barn. But Chelsea Maxwell, Chip’s daughter has plans.

Her finance, Ryan Muncy, runs a well-known restaurant in Chillicothe, and his entrepreneurial spirit seems to have rubbed off, giving Chelsea ideas about transforming the barn into an event center. Across Ohio, owners are converting old barns into wineries and venues for weddings and family reunions. They’re giving old barns a new life, which is a trend that Chelsea hopes to follow, putting restrooms into an adjacent small barn, running electric, and remodeling the lower level into a refreshment lounge. She even plans to be the first to have an event here – her own wedding. After all, it would be hard to pass on a barn called “Marvelous Maxwell.”

Sunshine Hill Farm, a small 15-acre corn and soybean farmstead, isn’t hard to miss when driving on State Route 180, just out of Kingston, thanks to this brilliant beacon of red and white, which can be seen for hundreds of yards in either direction. Its recent coat of fiery red paint and its twenty-eight-foot clerestory attract visitors, photographers, and artists: this true round barn is one of Ohio’s treasures. Peg Hays, sister of owner Chip Maxwell, emailed me and arranged our visit.

Using trees from adjacent woods – and a sawmill for cutting – Robert P. Maxwell, the family founder and great-grandfather of Chip and Peg, built the barn in 1910 and farmed 500 acres, keeping 100 head of beef cattle in the barn’s lower level. Over the years the farm passed down family lines until 1978 when three families divided up the 500 acres. Chip Maxwell and his wife Cherie were the lucky ones: they got the barn and eleven acres. But as the years passed by, a century of age caught up with the barn and the silo tilted, spelling impending doom.

According to a newspaper article, Cheri said, “You cannot put a price on sentimental value.” Yes, her husband Chip didn’t want to be on his deathbed, according to a newspaper article in the Chillicothe Gazette, Ohio’s oldest newspaper, founded in Cincinnati in 1793, knowing that he didn’t save the barn since his grandfather built it and his own dad cared so much for it. So he put his money where his sentiments were and paid a substantial sum to the Mt. Vernon Barn Company to save it. They uprighted the silo with cables and then stabilized the barn with new supports – mission accomplished. But, after such a costly restoration, what good is the barn? It doesn’t house crops or livestock. It’s just a beautiful old non-functioning barn. But Chelsea Maxwell, Chip’s daughter has plans.

Her finance, Ryan Muncy, runs a well-known restaurant in Chillicothe, and his entrepreneurial spirit seems to have rubbed off, giving Chelsea ideas about transforming the barn into an event center. Across Ohio, owners are converting old barns into wineries and venues for weddings and family reunions. They’re giving old barns a new life, which is a trend that Chelsea hopes to follow, putting restrooms into an adjacent small barn, running electric, and remodeling the lower level into a refreshment lounge. She even plans to be the first to have an event here – her own wedding. After all, it would be hard to pass on a barn called “Marvelous Maxwell.”

STARK COUNTY

"In Henry's Honor"

This oblong donut-shaped barn once house the horses of industrialist Henry Timken and his sons in Canton, Ohio. Fascinating story coming soon ...

This oblong donut-shaped barn once house the horses of industrialist Henry Timken and his sons in Canton, Ohio. Fascinating story coming soon ...

VINTON COUNTY

“The Jewels of Vinton County”

As I rounded a curve on County Road 21, also known as Shurtz Road, this large immaculate jewel appeared out of nowhere, making me hit the brakes. It stood there, close to the road, defying Father Time and resisting the advances of suburbia – a monument to an unknown barn builder, who constructed it in 1885, one of the earliest octagonal barns in Ohio.

I had tracked down the owner, Ronald Davis, through the county auditor, and sent him a letter since he resides out of the county. He chose to respond via a hand-written letter, giving me permission to visit, paint, and enter the barn, which I did. The interior was in good shape and the saw-cut timbers – instead of hand-hewn beams, typical of barns in the 1880s – indicated that the builder had access to a sawmill close by.

Mr. Davis wrote that George and Kate Shurtz purchased the land via a government grant in 1837, possibly a Revolutionary War warrant, and established the farm. They became prominent and prosperous farmers in the region and farmed 640 acres, while a relative of theirs farmed 300 acres on adjacent land. Accordingly, the Shurtz name now graces the country lane that leads directly to State Route 93, one of the main roads in this rural county, Ohio’s least populated.

The family’s farming success allowed them to build a delightful Hansel-and-Gretel-like sandstone block cottage, which, according to Mr. Davis, who has owned the farm since 1965, was broken into many times, once by burglars who stole all the antique furnishings. More recently – in July, 2019, the cottage was burned – most likely by arsonists. The multicolored hexagonal slate on the roof was costly in 1882 when the family built it as were the white gothic roof struts, which survived the fire. Unfortunately some of the roof has caved in, hinting that the end has neared.

The family farmed the land, though hilly and wooded, and used the barn to house dairy cows, work horses, and “buggy” horses, according to Mr. Davis. Eventually the Shurtz sisters inherited the farm and one of them, Minnie, a daughter of the original founder, was like a mother to Mr. Davis, who began working on the farm when he was 14. Since the sisters had no heirs, they gifted the farm to Mr. Davis, now 87, who’s not sure he’ll be around to read about this barn in my book. “The Shurtz family were of the best quality people I have ever known. It was a pleasure to have known such nice people,” he said.

Why does the title include “the jewels?” Yes, the octagonal barn is the main attraction, but it’s only one of several impressive buildings that remain. The barn across the road has a slate roof, a round steel corn crib still stands, and a chicken house in the distance is well protected with a green metal roof. Sadly, the stone house, once a historic gem, is now in its final stages, just one in this necklace of “jewels” – a memory of what was once a sparkling piece of Ohio history – the Shurtz family and their farm.

As I rounded a curve on County Road 21, also known as Shurtz Road, this large immaculate jewel appeared out of nowhere, making me hit the brakes. It stood there, close to the road, defying Father Time and resisting the advances of suburbia – a monument to an unknown barn builder, who constructed it in 1885, one of the earliest octagonal barns in Ohio.

I had tracked down the owner, Ronald Davis, through the county auditor, and sent him a letter since he resides out of the county. He chose to respond via a hand-written letter, giving me permission to visit, paint, and enter the barn, which I did. The interior was in good shape and the saw-cut timbers – instead of hand-hewn beams, typical of barns in the 1880s – indicated that the builder had access to a sawmill close by.

Mr. Davis wrote that George and Kate Shurtz purchased the land via a government grant in 1837, possibly a Revolutionary War warrant, and established the farm. They became prominent and prosperous farmers in the region and farmed 640 acres, while a relative of theirs farmed 300 acres on adjacent land. Accordingly, the Shurtz name now graces the country lane that leads directly to State Route 93, one of the main roads in this rural county, Ohio’s least populated.

The family’s farming success allowed them to build a delightful Hansel-and-Gretel-like sandstone block cottage, which, according to Mr. Davis, who has owned the farm since 1965, was broken into many times, once by burglars who stole all the antique furnishings. More recently – in July, 2019, the cottage was burned – most likely by arsonists. The multicolored hexagonal slate on the roof was costly in 1882 when the family built it as were the white gothic roof struts, which survived the fire. Unfortunately some of the roof has caved in, hinting that the end has neared.

The family farmed the land, though hilly and wooded, and used the barn to house dairy cows, work horses, and “buggy” horses, according to Mr. Davis. Eventually the Shurtz sisters inherited the farm and one of them, Minnie, a daughter of the original founder, was like a mother to Mr. Davis, who began working on the farm when he was 14. Since the sisters had no heirs, they gifted the farm to Mr. Davis, now 87, who’s not sure he’ll be around to read about this barn in my book. “The Shurtz family were of the best quality people I have ever known. It was a pleasure to have known such nice people,” he said.

Why does the title include “the jewels?” Yes, the octagonal barn is the main attraction, but it’s only one of several impressive buildings that remain. The barn across the road has a slate roof, a round steel corn crib still stands, and a chicken house in the distance is well protected with a green metal roof. Sadly, the stone house, once a historic gem, is now in its final stages, just one in this necklace of “jewels” – a memory of what was once a sparkling piece of Ohio history – the Shurtz family and their farm.

OREGON

DOUGLAS COUNTY

“Through a Looking Glass”

When surveyor Hoy Flournoy charted this land in 1846, he observed that the beautiful green grass of the valley reflected light almost as well as a looking glass, the pioneer’s term for a mirror. The name stuck and, in disregard for English teachers, the two words have remained joined together since the beginning. In 1852 the Lookingglass Store (still existing and offering a shelf of two-cent candy) was built as the terminus for the Oakland to Lookingglass stage route. It was also the beginning of another famous stagecoach trail, the Coos Bay Wagon Road, a name that survives, also. This road connected Douglas County to Coos Bay, beginning in 1872. The stage line continued up to 1914.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

When surveyor Hoy Flournoy charted this land in 1846, he observed that the beautiful green grass of the valley reflected light almost as well as a looking glass, the pioneer’s term for a mirror. The name stuck and, in disregard for English teachers, the two words have remained joined together since the beginning. In 1852 the Lookingglass Store (still existing and offering a shelf of two-cent candy) was built as the terminus for the Oakland to Lookingglass stage route. It was also the beginning of another famous stagecoach trail, the Coos Bay Wagon Road, a name that survives, also. This road connected Douglas County to Coos Bay, beginning in 1872. The stage line continued up to 1914.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

“The Claimant”

Samuel D. Evans, born in Madison County, Ohio, wanted more land than he had in Ohio and, motivated by the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, he traveled west to Oregon, settling in Douglas County in 1853. However, eight years later tragedy struck when Indians killed him during a cattle drive to northern California. Such were risks of the Oregon pioneers.

Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 in September of that year, in hopes of attracting settlers into the Oregon Territory. Thousands took advantage of the free land offer: 320 acres to every unmarried white male citizen of 18 years or older and 640 acres to every married couple. Though the act included Americans who were half Indian and half white, it excluded full-blooded Indians and, in essence, was designed, via treaties, to move them from their ancestral lands and into reservations. For thousands of years over 60 tribes lived in the Oregon Territory and at least 18 languages were spoken. But, by 1855 there were three reservations and by 1879 there were three more.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Samuel D. Evans, born in Madison County, Ohio, wanted more land than he had in Ohio and, motivated by the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, he traveled west to Oregon, settling in Douglas County in 1853. However, eight years later tragedy struck when Indians killed him during a cattle drive to northern California. Such were risks of the Oregon pioneers.

Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 in September of that year, in hopes of attracting settlers into the Oregon Territory. Thousands took advantage of the free land offer: 320 acres to every unmarried white male citizen of 18 years or older and 640 acres to every married couple. Though the act included Americans who were half Indian and half white, it excluded full-blooded Indians and, in essence, was designed, via treaties, to move them from their ancestral lands and into reservations. For thousands of years over 60 tribes lived in the Oregon Territory and at least 18 languages were spoken. But, by 1855 there were three reservations and by 1879 there were three more.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

HARNEY COUNTY

“The Cattle Barons”

From a distance this round barn looms as a tiny speck in vast sage-covered grasslands, against a stunning backdrop of the snow-capped Steens Mountains. Built in 1883 by cattleman Peter French, it’s witnessed a colorful page in the history of the West.

Antoine Sylvaille led a small party – the first white men to see this land – to trap beavers along local rivers in 1826, long before California (1850) and Oregon (1859) joined the Union. This was mostly Indian territory until the U.S. Army began to herd the natives onto reservations.

In 1849, about the time of the famous gold strike in California’s Sierra Madre range, John William French – later know as “Pete” – was born in Callaway County, Missouri. A year later his father moved the family to northern California and began sheep farming. However he soon found this rather mundane and around 1870 he began working on the cattle ranch of Dr. Hugh James Glenn, one of California’s early cattle barons. Originally from Virginia, Glenn earned a medical degree and served as a physician in the Mexican War. But his heart belonged to ranching.

French worked on the ranch with his father and, at 21, he registered to vote, listing his name as Peter, which was possibly bestowed on him by fellow workers, Mexican vaqueros. An industrious worker, Pete French became the son, in spirit at least, that Dr. Glenn never had – especially since his own children, raised indulgently, had no interest in manual labor. Quickly Pete rose to the job of foreman on Glenn’s ranch, which though large, was not enough land to feed his herd. So Dr. Glenn looked north into the Oregon Territory and selected French to lead his team of vaqueros on a cattle drive, taking 1,200 shorthorn cows into the high desert prairies of Oregon’s Steens Mountains. The rest of this essay will be posted eventually.

From a distance this round barn looms as a tiny speck in vast sage-covered grasslands, against a stunning backdrop of the snow-capped Steens Mountains. Built in 1883 by cattleman Peter French, it’s witnessed a colorful page in the history of the West.

Antoine Sylvaille led a small party – the first white men to see this land – to trap beavers along local rivers in 1826, long before California (1850) and Oregon (1859) joined the Union. This was mostly Indian territory until the U.S. Army began to herd the natives onto reservations.

In 1849, about the time of the famous gold strike in California’s Sierra Madre range, John William French – later know as “Pete” – was born in Callaway County, Missouri. A year later his father moved the family to northern California and began sheep farming. However he soon found this rather mundane and around 1870 he began working on the cattle ranch of Dr. Hugh James Glenn, one of California’s early cattle barons. Originally from Virginia, Glenn earned a medical degree and served as a physician in the Mexican War. But his heart belonged to ranching.

French worked on the ranch with his father and, at 21, he registered to vote, listing his name as Peter, which was possibly bestowed on him by fellow workers, Mexican vaqueros. An industrious worker, Pete French became the son, in spirit at least, that Dr. Glenn never had – especially since his own children, raised indulgently, had no interest in manual labor. Quickly Pete rose to the job of foreman on Glenn’s ranch, which though large, was not enough land to feed his herd. So Dr. Glenn looked north into the Oregon Territory and selected French to lead his team of vaqueros on a cattle drive, taking 1,200 shorthorn cows into the high desert prairies of Oregon’s Steens Mountains. The rest of this essay will be posted eventually.

LANE COUNTY

“An Immigrant’s Dream”

Though this barn was built between 1946 and 1949, well past the era of round barn construction, its uniqueness stems from its severely pitched roof and that it was built by an immigrant dairy farmer, who chose the design from a Midwest dairy magazine that promoted this as a more efficient design and less expensive to construct.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Though this barn was built between 1946 and 1949, well past the era of round barn construction, its uniqueness stems from its severely pitched roof and that it was built by an immigrant dairy farmer, who chose the design from a Midwest dairy magazine that promoted this as a more efficient design and less expensive to construct.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

PENNSYLVANIA

ADAMS COUNTY

“Beauty Queen”

Adams County is one of the richest historical regions in America. It’s only 30 miles from York, also known as Yorktown, which served as a transition from the battles of the American Revolution to those of the Civil War. York, founded in 1741 by settlers from Philadelphia, was the headquarters of the Continental Congress from September 1777 to June 1778 and, as such, has a claim to being one of the early capitals of the fledgling United States. York also became the largest northern town that was occupied by the Confederate army when Major General Early spent three days here in June, 1863. The York U.S. Army Hospital cared for thousands of Union soldiers wounded at the battles of Gettysburg and Antietam.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Adams County is one of the richest historical regions in America. It’s only 30 miles from York, also known as Yorktown, which served as a transition from the battles of the American Revolution to those of the Civil War. York, founded in 1741 by settlers from Philadelphia, was the headquarters of the Continental Congress from September 1777 to June 1778 and, as such, has a claim to being one of the early capitals of the fledgling United States. York also became the largest northern town that was occupied by the Confederate army when Major General Early spent three days here in June, 1863. The York U.S. Army Hospital cared for thousands of Union soldiers wounded at the battles of Gettysburg and Antietam.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

SOMERSET COUNTY

“The Onions of Somerset County”

Out of the hundreds of round barns built in this country, Simon O’Donnell’s barn – stretching the term a bit – stands out boldly: it may be America’s only round barn with an onion-shaped dome.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Out of the hundreds of round barns built in this country, Simon O’Donnell’s barn – stretching the term a bit – stands out boldly: it may be America’s only round barn with an onion-shaped dome.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.