INDIANA

DECATUR COUNTY

“The Wedding Cake”

Since several writers have used the phrase, a three-tiered wedding cake, to describe this round barn with its distinctive separate cupolas, it seemed fitting to title its painting and essay in the same way. Though it was built in 1908 by Strauther Van Pleak, the barn’s history traces back much further.

Strauther’s great grandfather, John Pleakenstalver, born in 1755 near Philadelphia, became a frontiersman, much like Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton. Some records indicate that he served with Daniel in Fort Boonesboro, Kentucky, and later became an ensign under George Rogers Clark in his Illinois campaign in 1778. Also during the Revolutionary War – in 1780 – John was one of the 256 signers of the Cumberland Compact, a document outlining rules of the settlers at Fort Nashborough, which later became Nashville, Tennessee.

After his marriage, he and his wife Esther moved to Morgan’s Station in 1791, a time when land – at a dollar an acre – was affordable but also a time when Indian skirmishes were still prevalent, probably motivating them to move the next spring to Mt. Sterling, Kentucky. The move was timed well since the settlers at Morgan’s, sensing no danger, dismantled the fort stockades, using the logs for firewood. In that spring, 1792, a large band of Shawnees killed many men, women, and children in this region, according to an eyewitness account of John Wade, Jr., the son of a settler at Morgan’s. Two miles away in Mt. Sterling, Pleakenstalver and his family were safe. They had 12 children.

CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THE STORY

Since several writers have used the phrase, a three-tiered wedding cake, to describe this round barn with its distinctive separate cupolas, it seemed fitting to title its painting and essay in the same way. Though it was built in 1908 by Strauther Van Pleak, the barn’s history traces back much further.

Strauther’s great grandfather, John Pleakenstalver, born in 1755 near Philadelphia, became a frontiersman, much like Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton. Some records indicate that he served with Daniel in Fort Boonesboro, Kentucky, and later became an ensign under George Rogers Clark in his Illinois campaign in 1778. Also during the Revolutionary War – in 1780 – John was one of the 256 signers of the Cumberland Compact, a document outlining rules of the settlers at Fort Nashborough, which later became Nashville, Tennessee.

After his marriage, he and his wife Esther moved to Morgan’s Station in 1791, a time when land – at a dollar an acre – was affordable but also a time when Indian skirmishes were still prevalent, probably motivating them to move the next spring to Mt. Sterling, Kentucky. The move was timed well since the settlers at Morgan’s, sensing no danger, dismantled the fort stockades, using the logs for firewood. In that spring, 1792, a large band of Shawnees killed many men, women, and children in this region, according to an eyewitness account of John Wade, Jr., the son of a settler at Morgan’s. Two miles away in Mt. Sterling, Pleakenstalver and his family were safe. They had 12 children.

CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THE STORY

FAYETTE COUNTY

“A Founding Father”

Nearly a spitting image of Straughter Pleak’s wedding cake barn, this one was built in 1904, seven years before Pleak’s. It, too, resembles the traditional cake, often shoved by the bride into the mouth of her new husband, sort of a message about who will be boss in the marriage. Though Straughter is given credit for building his own barn, original owners Thomas and Nancy Ranck hired one of Indiana’s famous round barn builders, Isaac McNamee. Interestingly, Fayette County is just north of Decatur County – where Pleak’s barn was built – lending some credence that Straughter may have seen this one before building his.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Nearly a spitting image of Straughter Pleak’s wedding cake barn, this one was built in 1904, seven years before Pleak’s. It, too, resembles the traditional cake, often shoved by the bride into the mouth of her new husband, sort of a message about who will be boss in the marriage. Though Straughter is given credit for building his own barn, original owners Thomas and Nancy Ranck hired one of Indiana’s famous round barn builders, Isaac McNamee. Interestingly, Fayette County is just north of Decatur County – where Pleak’s barn was built – lending some credence that Straughter may have seen this one before building his.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

KOSCIUSKO COUNTY

“Dodecagon”

Blame this one on the Greeks. If a hexagon is a six-sided polygon, and if a 10-sided structure is a decagon, then a 12-sided building, such as this barn, is a dodecagon. And, it’s a rare bird, one of the few dodecagonal barns left in America, according to its owner. It’s also a labor of love.

Jerred and Jennifer Reiff, he a general contractor, and she the principal of Columbia City High School, bought this farm in 2002. According to Jerred, the barn was a mess. “It had deteriorated badly,” Jerred explained, “but we wanted to save it. So, using his construction know-how, he poured concrete, lots of it, to stabilize the base of the barn, which was much more complicated than it sounds.

Unfortunately, they couldn’t salvage the nearby old farmhouse nor the spring house, used to keep the milk “cold” that the cows produced in the barn. Too far gone. But the barn, unique as it is, was worth keeping, one more feather in Indiana’s cap – a state with many “round” barns still existing. In fact, nearby Fulton County is known as the round barn capital of the world. It began in 1874 when Indiana’s first octagonal barn was built.

Before round barn construction ended in the 1930s, Indiana’s round barn count numbered 226, many of them in Fulton County. One of the barn builders, C.V. Kindig and Sons, though not enamored by the design, built many in northern Indiana, including 23 in Fulton County. The Reiff’s barn is located in adjacent Kosciusko County, not in Whitley, which, oddly, has none remaining. According to John Hanou, in his book, Round Indiana: Round Barns in the Hoosier State, of the 226 round barns originally in the state, 16 of them were 12-sided. Published in 1993, the book laments that more than 100 of these gems are gone. But that means that over 100 remain, which is far more than those left in other states.

Jerred explained that the circular design of the barn for milking cows served as the model for the modern honeycomb feeder, which can cost up to $250,000, making commercial dairy farming reserved for mega-farms. He said that this barn, begun in 1911, wasn’t finished until 1913. Why did it take three years? Regardless, the inside of this barn – and any round barn – is magnificent. At the top of the roof, wood shoots out in all directions – without any supporting beams – and is a joy to look at, keeping in mind that this was built over a century ago.

So, what’s to do with a small round barn? The Reiffs don’t have a big herd of dairy cows, nor do they have a massive honeycomb feeder, but they do have a purpose for this barn. They use it for storage and allow 4-H events to be held in it, giving this old barn a reason to exist. I’m sure, if it could talk, the barn would thank Jerred and Jennifer for deciding to save it from the bonfire and for letting it earn its keep. Even barns have pride.

Blame this one on the Greeks. If a hexagon is a six-sided polygon, and if a 10-sided structure is a decagon, then a 12-sided building, such as this barn, is a dodecagon. And, it’s a rare bird, one of the few dodecagonal barns left in America, according to its owner. It’s also a labor of love.

Jerred and Jennifer Reiff, he a general contractor, and she the principal of Columbia City High School, bought this farm in 2002. According to Jerred, the barn was a mess. “It had deteriorated badly,” Jerred explained, “but we wanted to save it. So, using his construction know-how, he poured concrete, lots of it, to stabilize the base of the barn, which was much more complicated than it sounds.

Unfortunately, they couldn’t salvage the nearby old farmhouse nor the spring house, used to keep the milk “cold” that the cows produced in the barn. Too far gone. But the barn, unique as it is, was worth keeping, one more feather in Indiana’s cap – a state with many “round” barns still existing. In fact, nearby Fulton County is known as the round barn capital of the world. It began in 1874 when Indiana’s first octagonal barn was built.

Before round barn construction ended in the 1930s, Indiana’s round barn count numbered 226, many of them in Fulton County. One of the barn builders, C.V. Kindig and Sons, though not enamored by the design, built many in northern Indiana, including 23 in Fulton County. The Reiff’s barn is located in adjacent Kosciusko County, not in Whitley, which, oddly, has none remaining. According to John Hanou, in his book, Round Indiana: Round Barns in the Hoosier State, of the 226 round barns originally in the state, 16 of them were 12-sided. Published in 1993, the book laments that more than 100 of these gems are gone. But that means that over 100 remain, which is far more than those left in other states.

Jerred explained that the circular design of the barn for milking cows served as the model for the modern honeycomb feeder, which can cost up to $250,000, making commercial dairy farming reserved for mega-farms. He said that this barn, begun in 1911, wasn’t finished until 1913. Why did it take three years? Regardless, the inside of this barn – and any round barn – is magnificent. At the top of the roof, wood shoots out in all directions – without any supporting beams – and is a joy to look at, keeping in mind that this was built over a century ago.

So, what’s to do with a small round barn? The Reiffs don’t have a big herd of dairy cows, nor do they have a massive honeycomb feeder, but they do have a purpose for this barn. They use it for storage and allow 4-H events to be held in it, giving this old barn a reason to exist. I’m sure, if it could talk, the barn would thank Jerred and Jennifer for deciding to save it from the bonfire and for letting it earn its keep. Even barns have pride.

LAKE COUNTY

“Perfection”

According to Orson Squire Fowler, editor of the American Phrenological Journal, the circle was the most perfect form, which might be traced to his days as a student at Amherst College, relatively close to the iconic round barn of the Shakers in western Massachusetts. However, in his book, The Octagon House: A Home For All, published in 1848, he emphasized the advantages of an octagonal building over one with right angles. Perhaps influenced by the work of Thomas Jefferson, whose favorite design was the octagonal, Fowler continued with a third edition, which he published in 1853 and which described the ideal farmstead as having both a house and barn in an octagonal shape. These books and subsequent articles prompted many throughout the east coast and the Midwest to use the octagon in both houses and barns.

Although Indiana has many beautiful and historic barns, these two polygonal barns with the adjacent round house, located west of Cedar Lake in Hanover Township, may represent the only farmstead conforming to Fowler’s concept of the ideal. In fact it may be one of only a few – if any – such farmsteads remaining in America. Sadly it did not make it into the National Register of Historic Places even though, as Fowler’s ideal farm, it was one of a kind. Regardless, it merits the title of this painting, “Perfection.”

According to Orson Squire Fowler, editor of the American Phrenological Journal, the circle was the most perfect form, which might be traced to his days as a student at Amherst College, relatively close to the iconic round barn of the Shakers in western Massachusetts. However, in his book, The Octagon House: A Home For All, published in 1848, he emphasized the advantages of an octagonal building over one with right angles. Perhaps influenced by the work of Thomas Jefferson, whose favorite design was the octagonal, Fowler continued with a third edition, which he published in 1853 and which described the ideal farmstead as having both a house and barn in an octagonal shape. These books and subsequent articles prompted many throughout the east coast and the Midwest to use the octagon in both houses and barns.

Although Indiana has many beautiful and historic barns, these two polygonal barns with the adjacent round house, located west of Cedar Lake in Hanover Township, may represent the only farmstead conforming to Fowler’s concept of the ideal. In fact it may be one of only a few – if any – such farmsteads remaining in America. Sadly it did not make it into the National Register of Historic Places even though, as Fowler’s ideal farm, it was one of a kind. Regardless, it merits the title of this painting, “Perfection.”

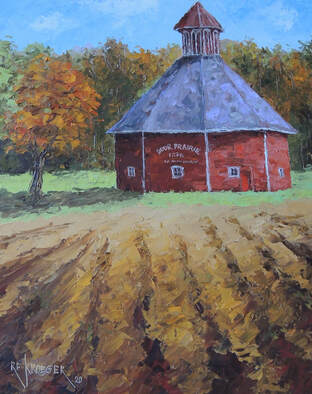

LAPORTE COUNTY

“Door on the Prairie”

LaPorte County was formed in 1832 and was named by French explorers who discovered a natural opening, an old Indian trail that resembled a door, leading to lands further west. To the west and southwards was the prairie and to the north and east were dense woods. It was an easy call: in French la porte means “door.” This nine-sided barn is situated south east of the county seat, La Porte, about equidistant from South Bend and Chicago. Marion Ridgeway built it in 1878, though the story begins much earlier.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

LaPorte County was formed in 1832 and was named by French explorers who discovered a natural opening, an old Indian trail that resembled a door, leading to lands further west. To the west and southwards was the prairie and to the north and east were dense woods. It was an easy call: in French la porte means “door.” This nine-sided barn is situated south east of the county seat, La Porte, about equidistant from South Bend and Chicago. Marion Ridgeway built it in 1878, though the story begins much earlier.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

VERMILLION COUNTY

“Unpainted”

Most barns receive several, if not many, coats of paint, usually red or white, over the course of a lifetime, but this one, located in a idyllic part of Vermillion County has never had one, a rarity in old barns. An image, captured in an autumn setting by Marsha Williamson Mohr, was so striking that it merited inclusion twice in her photography book, Indiana Barns. It also captivated me enough to use it as a photo reference for the painting. Some months after I’d finished, I came across another magnificent image of the barn, this one showing the barn’s reflection in still water, a photo taken by Scott Smith and published on his site. His stunning photo demands a painting, as well.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Most barns receive several, if not many, coats of paint, usually red or white, over the course of a lifetime, but this one, located in a idyllic part of Vermillion County has never had one, a rarity in old barns. An image, captured in an autumn setting by Marsha Williamson Mohr, was so striking that it merited inclusion twice in her photography book, Indiana Barns. It also captivated me enough to use it as a photo reference for the painting. Some months after I’d finished, I came across another magnificent image of the barn, this one showing the barn’s reflection in still water, a photo taken by Scott Smith and published on his site. His stunning photo demands a painting, as well.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.