Paintings Listed by Ohio County - R-Z

RICHLAND

“Bogie and Bacall”

If you’ve ever seen movies like To Have and Have Not or Casablanca or if you’ve ever listened to Bold Venture, their syndicated radio series that aired from 1951 to 1952, you can’t help liking Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. He was 44 when he met the nineteen-year-old actress on the set of To Have and Have Not and asked her to write her phone number on a matchbox. That was in 1944, a year when the United States and Britain had launched D-Day. A year later they married at Malabar Farm, located in rural Richland County. Though Bogart died in 1957 when Bacall was only 32, she treasured their marriage, even though she got only twelve years of him.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

If you’ve ever seen movies like To Have and Have Not or Casablanca or if you’ve ever listened to Bold Venture, their syndicated radio series that aired from 1951 to 1952, you can’t help liking Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. He was 44 when he met the nineteen-year-old actress on the set of To Have and Have Not and asked her to write her phone number on a matchbox. That was in 1944, a year when the United States and Britain had launched D-Day. A year later they married at Malabar Farm, located in rural Richland County. Though Bogart died in 1957 when Bacall was only 32, she treasured their marriage, even though she got only twelve years of him.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Bromfield’s Beauty”

Although I chose an old barn – built in 1890 and owned by the grandfather of Louis Bromfield – to represent Richland County in my book, that doesn’t diminish the importance of this more recently built barn, which serves, along with Malabar Farm, as his legacy to Ohio farming.

Louis Bromfield grew up in Mansfield and loved working on his grandfather’s farm but, as his life unfolded, he became a writer. After serving in World War I, he found work as a reporter in New York City, and began writing novels. Success followed: he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1927 and wrote many bestselling books, eventually moving his family to France, a county he came to love during the war. But, with trouble brewing in Germany in 1938, he returned to his roots in Richland County and bought the 1,000-acre Herring Farm in 1939, where he built a sprawling farmhouse and, as the son and grandson of farmers, began farming, continuing his family tradition. By 1942 the Malabar Farm was fully operational and, thanks to Bromfield’s organic and self-sustaining gardening on the farm, he was posthumously inducted into the Ohio Agricultural Hall of Fame. His children sold the farm in 1958 to a foundation, which, faced with foreclosure, passed it over to Ohio in 1976, enabling it to become Malabar State Park. Today it offers historical reenactments, gives tours, and keeps the Bromfield name alive.

While in France – both during World War I and in his expatriate years – he toured farms and observed farming methods, which, coupled with his upbringing on his grandfather’s farmstead, planted a seed inside him that grew. After much success as a novelist and Hollywood screenwriter, he acknowledged that seed and returned to his roots in Mansfield to begin farming. Bromfield liked to experiment on his farm and, with his public profile, was able to generate publicity for his agricultural ideas.

He also liked to entertain in his “modest” 32-room farmhouse, inviting celebrities, including Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, who married here in 1945. Others, like James Cagney, followed suit in establishing farms with sustainable practices. Today the state park offers a glimpse into early 20th century farming and, thanks to provisions made by the family foundation, Malabar is a working farm. The park offers tours of the farm and the mansion as well as produce from the farm in the gift shop.

However, tragedy struck this 1820s-era barn in April, 1993, when it burned – a fate that ended its long life. But it was re-built – duplicating the century-old tradition of installing mortise and tenon joints, joined by wooden pegs – thanks to the efforts of the Timber Framers Guild of North America, a non-profit educational organization located in Massachusetts. Three stylish cupolas adorn the crest of the roof – which is also protected by lightning rods – as the barn has been reborn, helping to preserve the legacy of Mansfield’s native son.

Although I chose an old barn – built in 1890 and owned by the grandfather of Louis Bromfield – to represent Richland County in my book, that doesn’t diminish the importance of this more recently built barn, which serves, along with Malabar Farm, as his legacy to Ohio farming.

Louis Bromfield grew up in Mansfield and loved working on his grandfather’s farm but, as his life unfolded, he became a writer. After serving in World War I, he found work as a reporter in New York City, and began writing novels. Success followed: he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1927 and wrote many bestselling books, eventually moving his family to France, a county he came to love during the war. But, with trouble brewing in Germany in 1938, he returned to his roots in Richland County and bought the 1,000-acre Herring Farm in 1939, where he built a sprawling farmhouse and, as the son and grandson of farmers, began farming, continuing his family tradition. By 1942 the Malabar Farm was fully operational and, thanks to Bromfield’s organic and self-sustaining gardening on the farm, he was posthumously inducted into the Ohio Agricultural Hall of Fame. His children sold the farm in 1958 to a foundation, which, faced with foreclosure, passed it over to Ohio in 1976, enabling it to become Malabar State Park. Today it offers historical reenactments, gives tours, and keeps the Bromfield name alive.

While in France – both during World War I and in his expatriate years – he toured farms and observed farming methods, which, coupled with his upbringing on his grandfather’s farmstead, planted a seed inside him that grew. After much success as a novelist and Hollywood screenwriter, he acknowledged that seed and returned to his roots in Mansfield to begin farming. Bromfield liked to experiment on his farm and, with his public profile, was able to generate publicity for his agricultural ideas.

He also liked to entertain in his “modest” 32-room farmhouse, inviting celebrities, including Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, who married here in 1945. Others, like James Cagney, followed suit in establishing farms with sustainable practices. Today the state park offers a glimpse into early 20th century farming and, thanks to provisions made by the family foundation, Malabar is a working farm. The park offers tours of the farm and the mansion as well as produce from the farm in the gift shop.

However, tragedy struck this 1820s-era barn in April, 1993, when it burned – a fate that ended its long life. But it was re-built – duplicating the century-old tradition of installing mortise and tenon joints, joined by wooden pegs – thanks to the efforts of the Timber Framers Guild of North America, a non-profit educational organization located in Massachusetts. Three stylish cupolas adorn the crest of the roof – which is also protected by lightning rods – as the barn has been reborn, helping to preserve the legacy of Mansfield’s native son.

“Does the Tax Man Cometh?”

This painting’s title is a distant cousin to Nobel Prize winning American playwright Eugene O'Neill’s Ice Man Cometh, a play he wrote in 1946. When I noticed this impressive barn – and another close by – I stopped, started looking around, and sizing up a composition. Just when I was about to walk up to the farmhouse door, a lady came out, asking me what I was doing. After I explained that I was barn touring on my own – since I had a few free hours before my fundraiser for the Mohican Historical Society, scheduled for the next day, she breathed a sigh of relief. “I thought you might be a tax appraiser from the county,” she said. No, I’ve been called many things, but never a tax man.

Diana Smith inherited the barn upon the passing of her mother, Grace Zimmerman, who purchased this little farmstead in 1983. She said that the original farmer, a Mr. Brown, raised chickens, but didn’t know much else about the barn. I didn’t ask her about the other red barn – with the same devil doors as Diana’s – that was only a few hundred yards down Rule Road. I’d guess the two were related somehow.

This one, a German forebay bank barn, built into a natural hillside, is full of hand-hewn beams and probably dates to the Civil War era. In fact, the forebay struts are hand-hewn on top and bottom only, leaving bark on the sides, which would have meant more labor to hew them as well. Farmers in those days were practical and didn’t like to waste time. An add-on extended the forebay, probably put on in the early 1900s.

The farm buildings suggest that these farmers did more than raise chickens. A good-sized corn crib and a milk house, both painted red to match the barn, hint at other farm production. And, it’s likely that, at the turn of the century, this farmer was doing well, evidenced by the delightful farmhouse, built in 1915, according to Diana. Two imposing triangular dormers, both covered with original slate, matching the roof, have been well maintained. Aluminum siding protects them as well as the exterior of the house. Seven white Doric pillars support the wrap-around porch, tempting the visitor to have a seat and enjoy the scenery. In the early 1900s, this farm must have been full of folks, livestock, and hustle and bustle.

Unfortunately, the bank behind the barn is shifting into it, threatening to end its days, even though some earth has been removed in an attempt to fight Mother Nature. But, when it rains, it rains, and, with time, mud will continue to slide down the hill. I gave Diana a recommendation to contact Rudy Christian, a barn restorer in nearby Wayne County. Perhaps he can help. Regardless, I’m glad I discovered this gem in time and Diana’s probably just as glad that I wasn’t the tax man.

This painting’s title is a distant cousin to Nobel Prize winning American playwright Eugene O'Neill’s Ice Man Cometh, a play he wrote in 1946. When I noticed this impressive barn – and another close by – I stopped, started looking around, and sizing up a composition. Just when I was about to walk up to the farmhouse door, a lady came out, asking me what I was doing. After I explained that I was barn touring on my own – since I had a few free hours before my fundraiser for the Mohican Historical Society, scheduled for the next day, she breathed a sigh of relief. “I thought you might be a tax appraiser from the county,” she said. No, I’ve been called many things, but never a tax man.

Diana Smith inherited the barn upon the passing of her mother, Grace Zimmerman, who purchased this little farmstead in 1983. She said that the original farmer, a Mr. Brown, raised chickens, but didn’t know much else about the barn. I didn’t ask her about the other red barn – with the same devil doors as Diana’s – that was only a few hundred yards down Rule Road. I’d guess the two were related somehow.

This one, a German forebay bank barn, built into a natural hillside, is full of hand-hewn beams and probably dates to the Civil War era. In fact, the forebay struts are hand-hewn on top and bottom only, leaving bark on the sides, which would have meant more labor to hew them as well. Farmers in those days were practical and didn’t like to waste time. An add-on extended the forebay, probably put on in the early 1900s.

The farm buildings suggest that these farmers did more than raise chickens. A good-sized corn crib and a milk house, both painted red to match the barn, hint at other farm production. And, it’s likely that, at the turn of the century, this farmer was doing well, evidenced by the delightful farmhouse, built in 1915, according to Diana. Two imposing triangular dormers, both covered with original slate, matching the roof, have been well maintained. Aluminum siding protects them as well as the exterior of the house. Seven white Doric pillars support the wrap-around porch, tempting the visitor to have a seat and enjoy the scenery. In the early 1900s, this farm must have been full of folks, livestock, and hustle and bustle.

Unfortunately, the bank behind the barn is shifting into it, threatening to end its days, even though some earth has been removed in an attempt to fight Mother Nature. But, when it rains, it rains, and, with time, mud will continue to slide down the hill. I gave Diana a recommendation to contact Rudy Christian, a barn restorer in nearby Wayne County. Perhaps he can help. Regardless, I’m glad I discovered this gem in time and Diana’s probably just as glad that I wasn’t the tax man.

“Rule Road”

After visiting the nearby intriguing barn complex, owned by Diana Smith, I noticed another wonderful barn in the distance, further back from Rule Road. Brightly painted red, the barn presumably was still functional and loved by its owners, who added matching quilt boards on its front. And add-on hinted at prosperity, too.

Though I could only view it road-side, I didn’t have a chance to meet the owners or see its insides. Fortunately, it will continue to thrive, thanks to the meticulous care it receives, and will continue to attract attention. After all, it got mine.

After visiting the nearby intriguing barn complex, owned by Diana Smith, I noticed another wonderful barn in the distance, further back from Rule Road. Brightly painted red, the barn presumably was still functional and loved by its owners, who added matching quilt boards on its front. And add-on hinted at prosperity, too.

Though I could only view it road-side, I didn’t have a chance to meet the owners or see its insides. Fortunately, it will continue to thrive, thanks to the meticulous care it receives, and will continue to attract attention. After all, it got mine.

“Striking”

Though I could only see this barn from Mill Road, St. Rt. 97, it captivated me. After having painted hundreds of barns, I felt that this one could compete for honors in the most photogenic department.

With a large supported forebay, the barn features two massive and decorated cupolas, each with 12 green louvers and a mint-green cap. Multiple green louvered windows dot the sides, which are painted white, weathered enough to expose an earlier coat of red.

Not far away stands an interesting farm house, not the typical cylindrical brick variety but one that sports traces of a Frank Lloyd Wright design, another unanswered question in this farmstead. Regardless of answers buried in history, the esthetics of this barn demand that it be called “striking,” a term that would bring smiles to its builder, unknown but remembered in this painting and essay.

Though I could only see this barn from Mill Road, St. Rt. 97, it captivated me. After having painted hundreds of barns, I felt that this one could compete for honors in the most photogenic department.

With a large supported forebay, the barn features two massive and decorated cupolas, each with 12 green louvers and a mint-green cap. Multiple green louvered windows dot the sides, which are painted white, weathered enough to expose an earlier coat of red.

Not far away stands an interesting farm house, not the typical cylindrical brick variety but one that sports traces of a Frank Lloyd Wright design, another unanswered question in this farmstead. Regardless of answers buried in history, the esthetics of this barn demand that it be called “striking,” a term that would bring smiles to its builder, unknown but remembered in this painting and essay.

“Deserted”

This composition appealed to me – a giant silo, sitting alone in the middle of a field of yellow-brown soybeans, patiently waiting for the harvester. At one time, the silo was probably surrounded by a barn and outbuildings, but today it stands alone; the small red barn in the distance may not have been part of this farmstead.

Route 97 winds behind the silo and Gatton Rocks Road veers off nearby. Left behind by its barn and farmhouse, yes, but not forgotten, this tall silo will continue to endure the ravages of Ohio’s cold winters and its hot summers, a memory of what once was here. Cement silos are tough, even if they are deserted.

This composition appealed to me – a giant silo, sitting alone in the middle of a field of yellow-brown soybeans, patiently waiting for the harvester. At one time, the silo was probably surrounded by a barn and outbuildings, but today it stands alone; the small red barn in the distance may not have been part of this farmstead.

Route 97 winds behind the silo and Gatton Rocks Road veers off nearby. Left behind by its barn and farmhouse, yes, but not forgotten, this tall silo will continue to endure the ravages of Ohio’s cold winters and its hot summers, a memory of what once was here. Cement silos are tough, even if they are deserted.

“Playing Possum”

This red bank barn was probably a German forebay at one time. Cement stone block has filled in its overhang, possibly done to add support and create additional storage space. Located on Possum Run Road, it conjured up thoughts of that odd-looking creature of the forest, the possum, the northernmost marsupial in the world.

Without much defense against predators, the opossum, or possum as it is commonly known, can fake death by becoming immobile, a condition that can last for hours. Usually nocturnal, the possum is often fond of scavenging roadkill and, if confronted by fast-moving vehicles, its fakery often results in its own demise, adding more roadkill to the highways.

Other animals, reptiles, and even insects can use this defensive maneuver. In fact, humans, if confronted by a bear and if escape is not possible, are often advised to “play possum,” lie face down on the ground, and appear dead, hoping the bear will get bored and roam away.

Though I could view this barn only from the road, it appeared to be functional and, with its metal roof, well taken care of, possibly enough to allow it to show vitality and never have to “play possum.”

This red bank barn was probably a German forebay at one time. Cement stone block has filled in its overhang, possibly done to add support and create additional storage space. Located on Possum Run Road, it conjured up thoughts of that odd-looking creature of the forest, the possum, the northernmost marsupial in the world.

Without much defense against predators, the opossum, or possum as it is commonly known, can fake death by becoming immobile, a condition that can last for hours. Usually nocturnal, the possum is often fond of scavenging roadkill and, if confronted by fast-moving vehicles, its fakery often results in its own demise, adding more roadkill to the highways.

Other animals, reptiles, and even insects can use this defensive maneuver. In fact, humans, if confronted by a bear and if escape is not possible, are often advised to “play possum,” lie face down on the ground, and appear dead, hoping the bear will get bored and roam away.

Though I could view this barn only from the road, it appeared to be functional and, with its metal roof, well taken care of, possibly enough to allow it to show vitality and never have to “play possum.”

“Abandoned, but Not Forgotten”

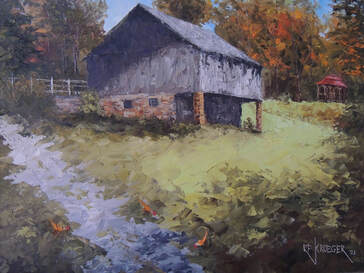

This little gray barn appeared abandoned when I passed it on Route 13, across from Vanderbilt Road, and about a half-mile from Trease Road. Forgotten now perhaps, but at one time it was likely part of a thriving farm.

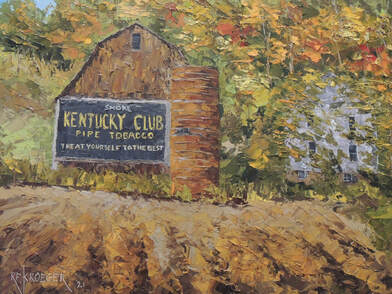

The name Vanderbilt conjures up images of The Breakers, a historic mansion on the famous cliff walk in Newport, Rhode Island, built by millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt II. However he didn’t build the first mansion on these grounds. Tobacco king Pierre Lorillard IV built that one, which burned seven years later after Vanderbilt purchased it in 1885. Vanderbilt, one of the wealthiest in the world at the time, commissioned famous New York City architect Richard Morris Hunt to build this palace, which took three years, completed in 1895, and the most impressive of all of Newport’s mansions. He died of a stroke four years later. At 55, he had only four years to enjoy Newport’s seaside views.

The Breakers left family ownership in 1972, when Newport’s Preservation Society bought it for $365,000, a small fraction of its replacement cost but agreed to allow Paul, Gladys and their mother to continue summering on the third floor, formerly servants’ quarters. After the mother died in 1998, her children are still allowed to spend summers here, hidden from the nearly half-million tourists who visit annually, making this the most-visited tourist attraction in Rhode Island.

Well, this little barn may not attract as many but, as it pulled in this artist to paint its image and write about it and as it may now be abandoned, it’s still a part of early Ohio history and, as such, will not be forgotten.

This little gray barn appeared abandoned when I passed it on Route 13, across from Vanderbilt Road, and about a half-mile from Trease Road. Forgotten now perhaps, but at one time it was likely part of a thriving farm.

The name Vanderbilt conjures up images of The Breakers, a historic mansion on the famous cliff walk in Newport, Rhode Island, built by millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt II. However he didn’t build the first mansion on these grounds. Tobacco king Pierre Lorillard IV built that one, which burned seven years later after Vanderbilt purchased it in 1885. Vanderbilt, one of the wealthiest in the world at the time, commissioned famous New York City architect Richard Morris Hunt to build this palace, which took three years, completed in 1895, and the most impressive of all of Newport’s mansions. He died of a stroke four years later. At 55, he had only four years to enjoy Newport’s seaside views.

The Breakers left family ownership in 1972, when Newport’s Preservation Society bought it for $365,000, a small fraction of its replacement cost but agreed to allow Paul, Gladys and their mother to continue summering on the third floor, formerly servants’ quarters. After the mother died in 1998, her children are still allowed to spend summers here, hidden from the nearly half-million tourists who visit annually, making this the most-visited tourist attraction in Rhode Island.

Well, this little barn may not attract as many but, as it pulled in this artist to paint its image and write about it and as it may now be abandoned, it’s still a part of early Ohio history and, as such, will not be forgotten.

“Rule Road”

After visiting the nearby intriguing barn complex, owned by Diana Smith, I noticed another wonderful barn in the distance, further back from Rule Road. Brightly painted red, the barn presumably was still functional and loved by its owners, who added matching quilt boards on its front. And add-on hinted at prosperity, too.

Though I could only view it road-side, I didn’t have a chance to meet the owners or see its insides. Fortunately, it will continue to thrive, thanks to the meticulous care it receives, and will continue to attract attention. After all, it got mine.

After visiting the nearby intriguing barn complex, owned by Diana Smith, I noticed another wonderful barn in the distance, further back from Rule Road. Brightly painted red, the barn presumably was still functional and loved by its owners, who added matching quilt boards on its front. And add-on hinted at prosperity, too.

Though I could only view it road-side, I didn’t have a chance to meet the owners or see its insides. Fortunately, it will continue to thrive, thanks to the meticulous care it receives, and will continue to attract attention. After all, it got mine.

“Locust Corners”

On my solo barn tour in the fall of 2021, this barn complex was the first one I found – located on St. Rt. 97, about a mile south of the Quality Inn, where I planned to spend the night. A sign, MID OHIO RESOURCES, next to mounds of sand and gravel, hinted that the land, including these two barns, had been sold to an excavating company.

The barns were large, one supported by two long planks, and were likely once part of a prosperous farm. And old farmhouse sat on the left side of the barns and, close to it, was a sign that read LOCUST CORNERS MARKET. Perhaps the farmer sold his produce here to passersby.

But why the name? Did locusts – the scourge of all farm crops – once pillage this area? Remembered in the Bible as the eighth plague of Exodus, locust swarms devoured crops in the western United States in the 19th century. In Wild West Magazine, a writer commented on the devastation, “The locusts soon scoured the fields of crops, the trees of leaves, every blade of grass, the wool off sheep, the harnesses off horses, the paint off wagons and the handles off pitchforks … The locusts, farmers grimly quipped, ‘ate everything but the mortgage.’”

In 1875 the largest locust swarm in history was recorded in the Midwest, a whopping 198,000 square miles. (California covers 163,696 square miles.) Though this storm of locusts was the largest in world history, the insects faded into oblivion – with their last sighting coming in 1902. Why they disappeared remains a mystery.

Another good question is what will happen to these two barns. Like so many others throughout Ohio, they may leave us without answers – another blank page in early Ohio agricultural history.

On my solo barn tour in the fall of 2021, this barn complex was the first one I found – located on St. Rt. 97, about a mile south of the Quality Inn, where I planned to spend the night. A sign, MID OHIO RESOURCES, next to mounds of sand and gravel, hinted that the land, including these two barns, had been sold to an excavating company.

The barns were large, one supported by two long planks, and were likely once part of a prosperous farm. And old farmhouse sat on the left side of the barns and, close to it, was a sign that read LOCUST CORNERS MARKET. Perhaps the farmer sold his produce here to passersby.

But why the name? Did locusts – the scourge of all farm crops – once pillage this area? Remembered in the Bible as the eighth plague of Exodus, locust swarms devoured crops in the western United States in the 19th century. In Wild West Magazine, a writer commented on the devastation, “The locusts soon scoured the fields of crops, the trees of leaves, every blade of grass, the wool off sheep, the harnesses off horses, the paint off wagons and the handles off pitchforks … The locusts, farmers grimly quipped, ‘ate everything but the mortgage.’”

In 1875 the largest locust swarm in history was recorded in the Midwest, a whopping 198,000 square miles. (California covers 163,696 square miles.) Though this storm of locusts was the largest in world history, the insects faded into oblivion – with their last sighting coming in 1902. Why they disappeared remains a mystery.

Another good question is what will happen to these two barns. Like so many others throughout Ohio, they may leave us without answers – another blank page in early Ohio agricultural history.

“Rhinestone Cowboy”

I liked this composition – a well-maintained bank barn with a forebay, partially hidden by the leaves of a graceful, spreading tree. Its metal roof showed that its owners want the barn to survive.

Located on Rhinehart Road, the barn, though not out West – where cowpokes work on open range – reminded me of Glen Campbell’s song, Rhinestone Cowboy. Well, I can only guess that one of the early owners – to paraphrase a line from Campbell’s song – might have been one day “riding out on a horse in a star-spangled rodeo.” Regardless of whether he did, this Richland County gem still sparkles, giving all who pass her by a glimpse into Ohio’s farming past.

I liked this composition – a well-maintained bank barn with a forebay, partially hidden by the leaves of a graceful, spreading tree. Its metal roof showed that its owners want the barn to survive.

Located on Rhinehart Road, the barn, though not out West – where cowpokes work on open range – reminded me of Glen Campbell’s song, Rhinestone Cowboy. Well, I can only guess that one of the early owners – to paraphrase a line from Campbell’s song – might have been one day “riding out on a horse in a star-spangled rodeo.” Regardless of whether he did, this Richland County gem still sparkles, giving all who pass her by a glimpse into Ohio’s farming past.

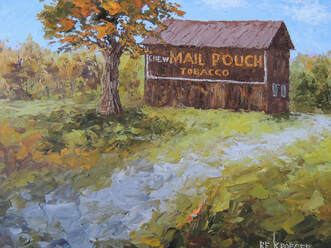

“Richland’s Mail Pouch”

On my first barn-hunting trip to Richland County in 2018, while driving through the countryside, I couldn’t help stopping at this Mail Pouch-logoed barn, its bright lettering visible 500 yards away. Without much free time left on this solo tour and many more miles to cover on my quest to capture an old barn in each of Ohio’s 88 counties, I had to forgo knocking on the farmhouse door. But I wanted to include this barn in my Ohio Barn Project, especially because the owner had enough pride to maintain this iconic logo. So I called the county auditor, got the owner’s address, and sent a snail mail letter, which was answered.

Mike and Mary Beth Whitney purchased this property in 2006 and decided to save the barn, which needed much work. They restored it inside and out, capped it with a metal roof, and added metal to the sides. They weren’t going to allow it to follow others into oblivion.

Mike explained that legendary Mail Pouch barn painter Harley Warrick painted it, possibly in 1982. Ten years later a local high school art teacher and his students repainted it. Mike said that he planned to paint the famous logo on the north and south side of the barn, as well. True aficionados, the Whitneys purchased a Mail Pouch barn model, painted by Harley, which hangs inside the barn. And, to further enhance this old barn, it houses their daughter’s two miniature horses, along with hay and sawdust, giving it another purpose, besides displaying Warrick’s trademark logo, quintessential Americana.

On my first barn-hunting trip to Richland County in 2018, while driving through the countryside, I couldn’t help stopping at this Mail Pouch-logoed barn, its bright lettering visible 500 yards away. Without much free time left on this solo tour and many more miles to cover on my quest to capture an old barn in each of Ohio’s 88 counties, I had to forgo knocking on the farmhouse door. But I wanted to include this barn in my Ohio Barn Project, especially because the owner had enough pride to maintain this iconic logo. So I called the county auditor, got the owner’s address, and sent a snail mail letter, which was answered.

Mike and Mary Beth Whitney purchased this property in 2006 and decided to save the barn, which needed much work. They restored it inside and out, capped it with a metal roof, and added metal to the sides. They weren’t going to allow it to follow others into oblivion.

Mike explained that legendary Mail Pouch barn painter Harley Warrick painted it, possibly in 1982. Ten years later a local high school art teacher and his students repainted it. Mike said that he planned to paint the famous logo on the north and south side of the barn, as well. True aficionados, the Whitneys purchased a Mail Pouch barn model, painted by Harley, which hangs inside the barn. And, to further enhance this old barn, it houses their daughter’s two miniature horses, along with hay and sawdust, giving it another purpose, besides displaying Warrick’s trademark logo, quintessential Americana.

ROSS

“Cory’s Cornerstone”

Webster’s dictionary defines a cornerstone as “an important quality or feature on which a particular thing depends or is based.” The word also connotes a sense of prosperity and pride, which this historic barn embellishes. The barn, even though built in 1938, is an important part of the Cory farmstead, a rare Ohio bicentennial farm and probably the oldest in Ross County. It has remained in the Cory family since 1800.

The patriarch, Nathan Cory, and his brother Stephen were surveyors in the Virginia Military District, which included much of what is now southern Ohio. They worked for Nathaniel Massie and his assistant surveyor Duncan McArthur, whose lives played a key part in developing this region of Ohio. Since this story is so long, it won't be posted here; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on Ohio barns.

Webster’s dictionary defines a cornerstone as “an important quality or feature on which a particular thing depends or is based.” The word also connotes a sense of prosperity and pride, which this historic barn embellishes. The barn, even though built in 1938, is an important part of the Cory farmstead, a rare Ohio bicentennial farm and probably the oldest in Ross County. It has remained in the Cory family since 1800.

The patriarch, Nathan Cory, and his brother Stephen were surveyors in the Virginia Military District, which included much of what is now southern Ohio. They worked for Nathaniel Massie and his assistant surveyor Duncan McArthur, whose lives played a key part in developing this region of Ohio. Since this story is so long, it won't be posted here; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on Ohio barns.

“Glenallan”

A vintage tractor sits in front of this barn, an intriguing clue to what a visitor might see inside its walls. Not only is this three-bay English threshing log barn extremely historic but it’s been meticulously maintained ever since the Hoyts took it over in 1939.

John Morris purchased – and perhaps founded – the farm circa 1810. Dendrochronology could determine if the barn had already been built or if it came a little later. Marriage marks on the rafters hint that the builder used the scribe rule to construct it, a method of timber framing brought over from Europe and used in the 18th century and early 19th century in America. Yankee ingenuity quickly replaced it with the more efficient square rule method.

According to Kate Hoyt, the family historian, Morris built a grist mill around 1827, in Slate Mills, a community named after this mill. He also helped build the nearby Adena mansion, home of Thomas Worthington, Ohio’s sixth governor. Since this story is so long, it won't be posted here; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on Ohio barns.

A vintage tractor sits in front of this barn, an intriguing clue to what a visitor might see inside its walls. Not only is this three-bay English threshing log barn extremely historic but it’s been meticulously maintained ever since the Hoyts took it over in 1939.

John Morris purchased – and perhaps founded – the farm circa 1810. Dendrochronology could determine if the barn had already been built or if it came a little later. Marriage marks on the rafters hint that the builder used the scribe rule to construct it, a method of timber framing brought over from Europe and used in the 18th century and early 19th century in America. Yankee ingenuity quickly replaced it with the more efficient square rule method.

According to Kate Hoyt, the family historian, Morris built a grist mill around 1827, in Slate Mills, a community named after this mill. He also helped build the nearby Adena mansion, home of Thomas Worthington, Ohio’s sixth governor. Since this story is so long, it won't be posted here; but it will definitely find a place in my second book on Ohio barns.

“Marvelous Maxwell”

Sunshine Hill Farm, a small 15-acre corn and soybean farmstead, isn’t hard to miss when driving on State Route 180, just out of Kingston, thanks to this brilliant beacon of red and white, which can be seen for hundreds of yards in either direction. Its recent coat of fiery red paint and its twenty-eight-foot clerestory attract visitors, photographers, and artists: this true round barn is one of Ohio’s treasures. Peg Hays, sister of owner Chip Maxwell, emailed me and arranged our visit.

Using trees from adjacent woods – and a sawmill for cutting – Robert P. Maxwell, the family founder and great-grandfather of Chip and Peg, built the barn in 1910 and farmed 500 acres, keeping 100 head of beef cattle in the barn’s lower level. Over the years the farm passed down family lines until 1978 when three families divided up the 500 acres. Chip Maxwell and his wife Cherie were the lucky ones: they got the barn and eleven acres. But as the years passed by, a century of age caught up with the barn and the silo tilted, spelling impending doom.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Dunlap’s Works”

Acres of corn now stretch for miles across State Route 104, not far from this historic farmstead, located on top of a gentle rise. The state route runs alongside the path of what was once the famous Ohio and Erie Canal, also passing near the farm. Even further steeped in Ohio history are the remnants of the early Hopewell Indian culture, one that built numerous mounds and earthen structures in this region. In their seminal research, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, the first book published – in 1848 – by the newly-formed Smithsonian Institution, authors Squier and Davis devote three pages to an area that they call “Dunlap’s Works,” a remarkable antiquity on the west bank of the Scioto River, relatively close to this farmstead.

They describe the main figure as rhomboidal in shape, with an “avenue of eleven hundred and thirty feet long extending to the south-east.” Beside the rhomboid lies a smaller structure, elliptical in shape, its purpose unknown. Leading out of the rhomboid is a circular work, 250 feet in diameter. The long avenue leads into the rhomboidal area through a large gateway, 120 feet wide. On the map and some distance from the river lies a house, labeled “Alms House,” though they offer no ownership or description. Though the authors submitted their voluminous manuscript in 1847, they likely inspected this area many years before that.

They mentioned a flood and a family, however. “The top of the truncated mound was made a place of refuge, during the high water of 1832, by a family, with their cattle, horses … numbering in all nearly a hundred.” The authors opened this mound, admittedly before they had opened others more significant, those which contained many articles from all parts of the country – copper from the north, obsidian from the west, shells from the ocean and gulf regions, and mica from North Carolina. But in the Dunlap mounds they found only skeletons, which they described as being those of “modern Indians” and fragments of pottery, made from decayed freshwater shells. They also commented on a number of large mounds just north of these works, which the authors claim was located about seven miles north of Chillicothe, twice the capital of Ohio. According to Betsy Moore, the seventh generation of Dunlaps and current owner with her husband Larry, in 1941 Ohio State University excavated a mound near their farmhouse and found a skeleton and some artifacts. The mound was then leveled.

Many early settlers of this area came from Virginia, likely disillusioned with slavery since Ohio was a free state from its infancy. The Dunlaps, rewarded with land grants for their service in the Revolutionary War, moved here from Dunlap Ridge, then a part of Virginia but now a part of West Virginia – after it became a state in 1863. They established this farm in 1829 in this location probably because they knew that the canal would pass by in a few years and therefore would be ideal for buying supplies and selling their excess farm production. According to Betsy, the family built this barn in 1829, hiring their freed slaves for its construction. They also built the farmhouse in the same year, firing the bricks on the property. The original acreage of over 7,000 acres, according to Betsy, was enough room for four homes for Dunlap families.

The barn is a classic example of a posted forebay, one with impressive sandstone blocks, probably cut in a quarry in nearby Waverly, about 16 miles away. Yes, transporting them on barges up the canal would have been much easier than by wagons, but the canal did not reach Chillicothe until 1831. Trees were cut on the farm and hewn into the barn’s beams, connected by mortise and tenon joints. Hay was stored on the main level, while livestock were kept in the lower level, which is supported mostly by giant hand-hewn beams, though there are some that are simply round tree skeletons, their bark removed. Perhaps the builders were tired of hewing at that point.

Today Betsy’s brothers farm soybeans, corn, wheat, and raise beef cattle and farm hay on 322 acres and use the barn to store lumber and equipment. Betsy and Larry, who acquired the farmstead – its barn, smokehouse, springhouse, and farmhouse – in 1991, plan to maintain their heritage by restoring the stone foundation, repairing rotten timbers, and securing sagging posts. Though their farmstead is located seven miles north of Chillicothe, it may well have been a part of the Dunlap’s Works, as described by Squier and Davis and also referred to at the Hopewell National Park, soon to become a world heritage UNESCO site. Today, though, the mounds have been turned into cornfields and a state road now runs where boats passed north and south on the canal. Betsy said that her grandfather Philip Dunlap, who took over the farm in 1931, said that a mound on the property was indeed leveled. Regardless, this historic farmstead and its barn, now approaching rare bicentennial status, will be remembered in this painting, framed in wood from the barn, and in the essay as “Dunlap’s Works,” quintessential Americana and a tribute to a long line of responsible stewardship.

Acres of corn now stretch for miles across State Route 104, not far from this historic farmstead, located on top of a gentle rise. The state route runs alongside the path of what was once the famous Ohio and Erie Canal, also passing near the farm. Even further steeped in Ohio history are the remnants of the early Hopewell Indian culture, one that built numerous mounds and earthen structures in this region. In their seminal research, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, the first book published – in 1848 – by the newly-formed Smithsonian Institution, authors Squier and Davis devote three pages to an area that they call “Dunlap’s Works,” a remarkable antiquity on the west bank of the Scioto River, relatively close to this farmstead.

They describe the main figure as rhomboidal in shape, with an “avenue of eleven hundred and thirty feet long extending to the south-east.” Beside the rhomboid lies a smaller structure, elliptical in shape, its purpose unknown. Leading out of the rhomboid is a circular work, 250 feet in diameter. The long avenue leads into the rhomboidal area through a large gateway, 120 feet wide. On the map and some distance from the river lies a house, labeled “Alms House,” though they offer no ownership or description. Though the authors submitted their voluminous manuscript in 1847, they likely inspected this area many years before that.

They mentioned a flood and a family, however. “The top of the truncated mound was made a place of refuge, during the high water of 1832, by a family, with their cattle, horses … numbering in all nearly a hundred.” The authors opened this mound, admittedly before they had opened others more significant, those which contained many articles from all parts of the country – copper from the north, obsidian from the west, shells from the ocean and gulf regions, and mica from North Carolina. But in the Dunlap mounds they found only skeletons, which they described as being those of “modern Indians” and fragments of pottery, made from decayed freshwater shells. They also commented on a number of large mounds just north of these works, which the authors claim was located about seven miles north of Chillicothe, twice the capital of Ohio. According to Betsy Moore, the seventh generation of Dunlaps and current owner with her husband Larry, in 1941 Ohio State University excavated a mound near their farmhouse and found a skeleton and some artifacts. The mound was then leveled.

Many early settlers of this area came from Virginia, likely disillusioned with slavery since Ohio was a free state from its infancy. The Dunlaps, rewarded with land grants for their service in the Revolutionary War, moved here from Dunlap Ridge, then a part of Virginia but now a part of West Virginia – after it became a state in 1863. They established this farm in 1829 in this location probably because they knew that the canal would pass by in a few years and therefore would be ideal for buying supplies and selling their excess farm production. According to Betsy, the family built this barn in 1829, hiring their freed slaves for its construction. They also built the farmhouse in the same year, firing the bricks on the property. The original acreage of over 7,000 acres, according to Betsy, was enough room for four homes for Dunlap families.

The barn is a classic example of a posted forebay, one with impressive sandstone blocks, probably cut in a quarry in nearby Waverly, about 16 miles away. Yes, transporting them on barges up the canal would have been much easier than by wagons, but the canal did not reach Chillicothe until 1831. Trees were cut on the farm and hewn into the barn’s beams, connected by mortise and tenon joints. Hay was stored on the main level, while livestock were kept in the lower level, which is supported mostly by giant hand-hewn beams, though there are some that are simply round tree skeletons, their bark removed. Perhaps the builders were tired of hewing at that point.

Today Betsy’s brothers farm soybeans, corn, wheat, and raise beef cattle and farm hay on 322 acres and use the barn to store lumber and equipment. Betsy and Larry, who acquired the farmstead – its barn, smokehouse, springhouse, and farmhouse – in 1991, plan to maintain their heritage by restoring the stone foundation, repairing rotten timbers, and securing sagging posts. Though their farmstead is located seven miles north of Chillicothe, it may well have been a part of the Dunlap’s Works, as described by Squier and Davis and also referred to at the Hopewell National Park, soon to become a world heritage UNESCO site. Today, though, the mounds have been turned into cornfields and a state road now runs where boats passed north and south on the canal. Betsy said that her grandfather Philip Dunlap, who took over the farm in 1931, said that a mound on the property was indeed leveled. Regardless, this historic farmstead and its barn, now approaching rare bicentennial status, will be remembered in this painting, framed in wood from the barn, and in the essay as “Dunlap’s Works,” quintessential Americana and a tribute to a long line of responsible stewardship.

“The Double”

This barn, probably built before the Civil War, is a rare example of a double forebay. Although the Pennsylvania German-style bank barn – with one forebay – is more common, its cousin, the double forebay, is hardly ever seen. Normally, though building a barn into a natural hillside would preclude being able to include a second forebay alongside the hill, this one does just that.

In neighboring Fairfield County, near the village of Baltimore, the county park district, realizing the rarity of such a double forebay barn, dismantled it in 2005 and is currently rebuilding it in Smeck Park. Although they retained the original gigantic sandstone blocks, the timbers were too weak to re-use. So, though built in 1841 – the date and Fetter’s name are inscribed in one of the stones – the barn will be replicated, not reassembled. Fetter’s barn was built in the same era as this one, although it appears to be much larger than this one – at 42 by 36 feet, a more typical size for a pre-Civil War barn.

Although the early ownership of this barn may remain unknown, John Payne, director of the Pump House Art Center and barn scout for me, told me that his father Edwin purchased the barn in 1952. A high school biology teacher, Edwin must have had a soft spot for old barns and may have realized that there just aren’t many double forebay barns still standing.

So, in 1968 he restored the barn, spending more money on the restoration than he did to buy the entire farm! He hired an 80-year-old, who knew the ancient art of hand-hewing and who replaced siding, which 50 years later has turned into a rustic weathered gray.

But, the foundation needed help and since Edwin father owned and operated drive-in theaters in the area, he knew about a plentiful supply of sandstone blocks, close to his theaters. He figured that these blocks, part of locks on the Ohio and Erie Canal, just south of Chillicothe, would be ideal for a foundation and so he purchased them from the landowner and hired a Mr. Hammond to build a new foundation. Though a bricklayer by trade, Hammond knew how to cut and shape the blocks, which gave this old barn a foundation that looks as if it were built in the 1830s, the era when the canal was completed. As we walked around, admiring the restoration, I noticed a small man door that begged to be painted; so I obliged.

Current owner Carl Eblin, who lives in Columbus, purchased the 72-acre farm in 2016. Fortunately, he plans to save the barn and renovate the farmhouse. That’s great news since this is one of the few double forebay barns still standing in Ohio. Hopefully it will remain standing for decades to come.

This barn, probably built before the Civil War, is a rare example of a double forebay. Although the Pennsylvania German-style bank barn – with one forebay – is more common, its cousin, the double forebay, is hardly ever seen. Normally, though building a barn into a natural hillside would preclude being able to include a second forebay alongside the hill, this one does just that.

In neighboring Fairfield County, near the village of Baltimore, the county park district, realizing the rarity of such a double forebay barn, dismantled it in 2005 and is currently rebuilding it in Smeck Park. Although they retained the original gigantic sandstone blocks, the timbers were too weak to re-use. So, though built in 1841 – the date and Fetter’s name are inscribed in one of the stones – the barn will be replicated, not reassembled. Fetter’s barn was built in the same era as this one, although it appears to be much larger than this one – at 42 by 36 feet, a more typical size for a pre-Civil War barn.

Although the early ownership of this barn may remain unknown, John Payne, director of the Pump House Art Center and barn scout for me, told me that his father Edwin purchased the barn in 1952. A high school biology teacher, Edwin must have had a soft spot for old barns and may have realized that there just aren’t many double forebay barns still standing.

So, in 1968 he restored the barn, spending more money on the restoration than he did to buy the entire farm! He hired an 80-year-old, who knew the ancient art of hand-hewing and who replaced siding, which 50 years later has turned into a rustic weathered gray.

But, the foundation needed help and since Edwin father owned and operated drive-in theaters in the area, he knew about a plentiful supply of sandstone blocks, close to his theaters. He figured that these blocks, part of locks on the Ohio and Erie Canal, just south of Chillicothe, would be ideal for a foundation and so he purchased them from the landowner and hired a Mr. Hammond to build a new foundation. Though a bricklayer by trade, Hammond knew how to cut and shape the blocks, which gave this old barn a foundation that looks as if it were built in the 1830s, the era when the canal was completed. As we walked around, admiring the restoration, I noticed a small man door that begged to be painted; so I obliged.

Current owner Carl Eblin, who lives in Columbus, purchased the 72-acre farm in 2016. Fortunately, he plans to save the barn and renovate the farmhouse. That’s great news since this is one of the few double forebay barns still standing in Ohio. Hopefully it will remain standing for decades to come.

“Mounds and Marriage Marks”

This barn, incredibly unique architecturally, sits on ancient land, occupied 2,000 years ago by the Hopewell Culture of Native Americans. They located along the banks of the Scioto River and its tributary, Paint Creek, and built extensive earthworks, circles, and mounds in what will be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2023.

Ohio was rich in Indian mounds in the 1700s, many overgrown by forests, which settlers eventually trimmed down to plant their crops and graze livestock. In establishing their farms, they often leveled these mounds, reducing their numbers from an estimated 10,000 to around 500. In this location there are four major sites, all part of the National Park system, which stretch approximately 12 miles. When I visited, a park ranger, Dr. Bret Ruby, an archaeologist with a specialty in the Hopewell Culture, gave me a guided tour and took me to this barn. Click here for the rest of this story.

This barn, incredibly unique architecturally, sits on ancient land, occupied 2,000 years ago by the Hopewell Culture of Native Americans. They located along the banks of the Scioto River and its tributary, Paint Creek, and built extensive earthworks, circles, and mounds in what will be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2023.

Ohio was rich in Indian mounds in the 1700s, many overgrown by forests, which settlers eventually trimmed down to plant their crops and graze livestock. In establishing their farms, they often leveled these mounds, reducing their numbers from an estimated 10,000 to around 500. In this location there are four major sites, all part of the National Park system, which stretch approximately 12 miles. When I visited, a park ranger, Dr. Bret Ruby, an archaeologist with a specialty in the Hopewell Culture, gave me a guided tour and took me to this barn. Click here for the rest of this story.

“The Father of Ohio’s Statehood”

This barn, a reconstruction, is located on the grounds of Chillicothe’s Adena Mansion, the estate of Ohio’s first senator and its sixth governor, Thomas Worthington. Though only 300 of the original 2,000 acres remain, the grounds have been maintained well and tours are given daily through the mansion.

Born in 1773 in the Colony of Virginia, Thomas Worthington was the youngest of six children in a family that, while not as wealthy as most Virginia planters – like Washington and Jefferson – was well off. Robert Worthington, father of Thomas, worked as a farmer, surveyor, and land speculator and resolved to serve in the Revolutionary War under George Washington, whom he helped during surveying. However, when about to raise a troop of calvary at his own expense, he suddenly got sick and died in October, 1779. A few months later his wife died, leaving six-year-old Thomas an orphan and in the care of his brothers. Each inherited about 1,500 acres of the family estate. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY.

This barn, a reconstruction, is located on the grounds of Chillicothe’s Adena Mansion, the estate of Ohio’s first senator and its sixth governor, Thomas Worthington. Though only 300 of the original 2,000 acres remain, the grounds have been maintained well and tours are given daily through the mansion.

Born in 1773 in the Colony of Virginia, Thomas Worthington was the youngest of six children in a family that, while not as wealthy as most Virginia planters – like Washington and Jefferson – was well off. Robert Worthington, father of Thomas, worked as a farmer, surveyor, and land speculator and resolved to serve in the Revolutionary War under George Washington, whom he helped during surveying. However, when about to raise a troop of calvary at his own expense, he suddenly got sick and died in October, 1779. A few months later his wife died, leaving six-year-old Thomas an orphan and in the care of his brothers. Each inherited about 1,500 acres of the family estate. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THIS STORY.

SANDUSKY

“Chickens Galore”

This must have been some sight – back in the day – when the complex of barns produced thousands and thousands of chickens and their eggs. On the right side is a tall feed mill, which prepared food for the chickens. To the left are two barns – one a corn crib and one for hatchlings and storage. And behind them looms the giant chicken barn, all six stories of it, with its wooden-encased elevator shaft, which was used to transport the feed to the various levels. A slate roof has protected it well over the centuries.

Yes, that’s right – six stories. I can verify this since I hiked up ladders to see each one of them, courtesy of our guide Betty Moyer, who owns the farm with her sister-in-law. Betty’s husband Robert and his twin brother Roger have passed away, the fifth generation of the Moyer family to own this farm. And it’s old. The farm house dates to 1840 and the barn may have been built around the same time, evidenced by its many rustic hand-hewn timbers.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This must have been some sight – back in the day – when the complex of barns produced thousands and thousands of chickens and their eggs. On the right side is a tall feed mill, which prepared food for the chickens. To the left are two barns – one a corn crib and one for hatchlings and storage. And behind them looms the giant chicken barn, all six stories of it, with its wooden-encased elevator shaft, which was used to transport the feed to the various levels. A slate roof has protected it well over the centuries.

Yes, that’s right – six stories. I can verify this since I hiked up ladders to see each one of them, courtesy of our guide Betty Moyer, who owns the farm with her sister-in-law. Betty’s husband Robert and his twin brother Roger have passed away, the fifth generation of the Moyer family to own this farm. And it’s old. The farm house dates to 1840 and the barn may have been built around the same time, evidenced by its many rustic hand-hewn timbers.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

SCIOTO

“Shawnee Turf”

It was the land of the Shawnees, a nomadic tribe that migrated extensively along the eastern seaboard in the 1700s, following animal movement, eventually establishing what historians call Lower Shawnee Town in the early 1700s on the banks of the Ohio River near its confluence with the Scioto, a river named for the Indian word for deer hunting. By the mid-1730s the settlement had become an important trading area with the French and the British. The great flood of 1753 wiped out the villages, which were re-built on the site of present-day Portsmouth, not far from this barn, located on the Ohio side of the river and only a few miles west of the city on Moore’s Lane. At that time the Ohio Country and Kentucky were vast forests, a communal hunting ground for many Native American tribes.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

SENECA

“The Underground”

Barn scouts Judy and Mel introduced me to Roger Kinney, the owner of this old barn, built in the early 1900s, judging from its construction. The 88-year-old Roger, engaging and lively, told us that his parents bought the farm around 1910, probably from his grandparents. Originally, the settlers lived in a log cabin, close to the barn, and further back they stored food in a cave underground, which served as a refrigerator, au naturel.

Roger told us that the barn was built near Fremont to store wood for the steam locomotives that passed by on the tracks that were close to the barn, connecting Lodi, Tiffin, and Fostoria. Coal replaced wood to fuel the engines, so the surplus barn was sold to Roger’s father, who moved it to its present site on the family farm. Today the railroad tracks are gone, but the barn still contributes historically by storing antiques for the nearby Lyme Village, which has preserved several old buildings, giving a glimpse into life in the 1800s.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Barn scouts Judy and Mel introduced me to Roger Kinney, the owner of this old barn, built in the early 1900s, judging from its construction. The 88-year-old Roger, engaging and lively, told us that his parents bought the farm around 1910, probably from his grandparents. Originally, the settlers lived in a log cabin, close to the barn, and further back they stored food in a cave underground, which served as a refrigerator, au naturel.

Roger told us that the barn was built near Fremont to store wood for the steam locomotives that passed by on the tracks that were close to the barn, connecting Lodi, Tiffin, and Fostoria. Coal replaced wood to fuel the engines, so the surplus barn was sold to Roger’s father, who moved it to its present site on the family farm. Today the railroad tracks are gone, but the barn still contributes historically by storing antiques for the nearby Lyme Village, which has preserved several old buildings, giving a glimpse into life in the 1800s.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

SHELBY

“Botkins”

Years ago, whenever I drove south on I-75 along Shelby County, I saw a quaint old barn, not far off the highway. Somewhat deteriorated, its cupola tilted and boards missing, it called out to me. So, on my return trip from northern Indiana on Veterans Day weekend in 2018, I decided I’d stop to find it. I exited the highway at the village of Botkins, just across the county line – south of Auglaize County. After getting gas and a coffee at the Gulf Station – yes, they still exist – I went down a few roads, looking for my barn. But no luck. Perhaps it was dismantled. Yes, probably it was. My loss.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Years ago, whenever I drove south on I-75 along Shelby County, I saw a quaint old barn, not far off the highway. Somewhat deteriorated, its cupola tilted and boards missing, it called out to me. So, on my return trip from northern Indiana on Veterans Day weekend in 2018, I decided I’d stop to find it. I exited the highway at the village of Botkins, just across the county line – south of Auglaize County. After getting gas and a coffee at the Gulf Station – yes, they still exist – I went down a few roads, looking for my barn. But no luck. Perhaps it was dismantled. Yes, probably it was. My loss.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Shelby’s Diamond”

Diamonds are valuable gems, a good analogy for this superb octagonal barn on the fairgrounds of Shelby County. Round barns, a category that includes true circular and polygonal shapes, are extremely rare and represent a fad of barn building that didn’t last and comprised less than one percent of barns built in that era – from 1875 to about 1930. In Ohio there are only about two dozen remaining.

Though there were a handful of round barns built before 1875, the shape didn’t interest the average farmer, even though the country’s first president, farmer George Washington, built a 16-sided threshing barn in 1793 and the Shakers of western Massachusetts built a true round barn of stone in 1826. Oddly enough, another round barn, this one of orange brick, was built in 1860 in Champaign County. None followed its lead. Farmers figured that rectangular barns were easier and less expensive to build, compared to round ones. They were right. The shape just didn’t catch on.

Then, in 1875, after losing three conventional barns to fire, New York State’s Eliot Stewart built an octagonal barn, which he figured would survive. As the editor of the Buffalo Livestock Journal from 1872 to 1876, he was influential in the agricultural community and by 1884 he claimed there were 30-40 octagonals, mostly in New York but also as far away as Mississippi. However, they still remained less than one percent of all barns built.

The next phase was the circular barn, popularized by Wisconsin’s Professor Franklin King, who built one for his brother in 1890 and publicized it in many ag journals. This shape did catch on … for about 30 years and was geared for the dairy farmer, who could gather his cows around a central silo, also introduced by King. Still, the average farmer chose the traditional barn and ignored the “self-supporting” roof of the rounds, which proponents claimed to be wind resistant. They weren’t.

Today the plaque over the barn’s entrance reads, “Community Hall, Community Foundation of Shelby County.” Though it’s still being used, there are rumors of its demise. Now, if you had a diamond ring, you surely would be cautious around a drain, being careful not to let it slip off and then down the drain. Likewise, Shelby County should take great care to preserve this octagonal gem, one of the few of its kind left in Ohio. Indeed, it’s one of the county’s true diamonds.

Diamonds are valuable gems, a good analogy for this superb octagonal barn on the fairgrounds of Shelby County. Round barns, a category that includes true circular and polygonal shapes, are extremely rare and represent a fad of barn building that didn’t last and comprised less than one percent of barns built in that era – from 1875 to about 1930. In Ohio there are only about two dozen remaining.

Though there were a handful of round barns built before 1875, the shape didn’t interest the average farmer, even though the country’s first president, farmer George Washington, built a 16-sided threshing barn in 1793 and the Shakers of western Massachusetts built a true round barn of stone in 1826. Oddly enough, another round barn, this one of orange brick, was built in 1860 in Champaign County. None followed its lead. Farmers figured that rectangular barns were easier and less expensive to build, compared to round ones. They were right. The shape just didn’t catch on.

Then, in 1875, after losing three conventional barns to fire, New York State’s Eliot Stewart built an octagonal barn, which he figured would survive. As the editor of the Buffalo Livestock Journal from 1872 to 1876, he was influential in the agricultural community and by 1884 he claimed there were 30-40 octagonals, mostly in New York but also as far away as Mississippi. However, they still remained less than one percent of all barns built.

The next phase was the circular barn, popularized by Wisconsin’s Professor Franklin King, who built one for his brother in 1890 and publicized it in many ag journals. This shape did catch on … for about 30 years and was geared for the dairy farmer, who could gather his cows around a central silo, also introduced by King. Still, the average farmer chose the traditional barn and ignored the “self-supporting” roof of the rounds, which proponents claimed to be wind resistant. They weren’t.

Today the plaque over the barn’s entrance reads, “Community Hall, Community Foundation of Shelby County.” Though it’s still being used, there are rumors of its demise. Now, if you had a diamond ring, you surely would be cautious around a drain, being careful not to let it slip off and then down the drain. Likewise, Shelby County should take great care to preserve this octagonal gem, one of the few of its kind left in Ohio. Indeed, it’s one of the county’s true diamonds.

“Photogenic”

The saying, “Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder,” applies to this barn, about as beautiful as any artist or photographer could hope for. It’s another example of a farmer’s becoming prosperous and deciding to increase storage space by adding on – a newer section, also sporting a gambrel roof, is attached.

Though the farmhouse dates to 1882 – and the oak tree to its left goes back even earlier - Frank Gerry Davidson built this barn in 1923 with his cousin’s firm, the Gerry Construction Company. Chances are good that one or more barns serviced this farm throughout the 19th century. Carl Davidson ran the farm until he passed in 2002.

Barn scout Roger said that Matt Davidson takes care of this barn on a farm his dad, Ned Davidson, owns – along with his brothers John and Steve. And Matt’s done a good job – the metal roofs, abutting one another, are in excellent shape, guaranteeing many more years for photographers passing by this picture-perfect piece of Ohio history.

The saying, “Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder,” applies to this barn, about as beautiful as any artist or photographer could hope for. It’s another example of a farmer’s becoming prosperous and deciding to increase storage space by adding on – a newer section, also sporting a gambrel roof, is attached.

Though the farmhouse dates to 1882 – and the oak tree to its left goes back even earlier - Frank Gerry Davidson built this barn in 1923 with his cousin’s firm, the Gerry Construction Company. Chances are good that one or more barns serviced this farm throughout the 19th century. Carl Davidson ran the farm until he passed in 2002.

Barn scout Roger said that Matt Davidson takes care of this barn on a farm his dad, Ned Davidson, owns – along with his brothers John and Steve. And Matt’s done a good job – the metal roofs, abutting one another, are in excellent shape, guaranteeing many more years for photographers passing by this picture-perfect piece of Ohio history.

“The Triumvirate”

Though “Maple Lane Farm” is scripted onto the silo, I decided to call this painting, “The Triumvirate,” recalling times of the Romans. The first triumvirate (a Latin word meaning “three men”) of ancient Rome was a political alliance among three powerful Romans: Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus which, from 60 BC until 53 BC, dominated the politics of the Roman Republic, and, four years later, led to the dictatorship of Julius Caesar. Though his rule was only a few years, ending with his murder, his son Augustus, known as Octavian, became Rome’s first emperor.

Perhaps the farm’s owners, Eric and Gay Smith, should name their three handsome barns, all with protective metal roofs and fresh coats of red paint, along with solid course rubble limestone foundations. Let’s see, which one should be Julius Caesar?

Though “Maple Lane Farm” is scripted onto the silo, I decided to call this painting, “The Triumvirate,” recalling times of the Romans. The first triumvirate (a Latin word meaning “three men”) of ancient Rome was a political alliance among three powerful Romans: Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus which, from 60 BC until 53 BC, dominated the politics of the Roman Republic, and, four years later, led to the dictatorship of Julius Caesar. Though his rule was only a few years, ending with his murder, his son Augustus, known as Octavian, became Rome’s first emperor.

Perhaps the farm’s owners, Eric and Gay Smith, should name their three handsome barns, all with protective metal roofs and fresh coats of red paint, along with solid course rubble limestone foundations. Let’s see, which one should be Julius Caesar?

“Bicentennial”

This farm, founded by the Staley family in 1837, is quickly approaching bicentennial status, which the state of Ohio awards to a family that has owned its farm for 200 years.

Barn scout Roger and I met Helen Ward, who acquired the farm with her husband Greg in 2003. Her great grandparents were Staleys. They allow their 4-H’er grandson to use the barn for raising pigs and they also use the barn for storage. Protected by four lightning rods, it’s in excellent condition.

Helen told us that they still own 100 acres land (I inserted corn stalks into the foreground) and that they are looking forward to earning that exclusive Ohio farm designation of being a bicentennial. Only a few decades away …

This farm, founded by the Staley family in 1837, is quickly approaching bicentennial status, which the state of Ohio awards to a family that has owned its farm for 200 years.

Barn scout Roger and I met Helen Ward, who acquired the farm with her husband Greg in 2003. Her great grandparents were Staleys. They allow their 4-H’er grandson to use the barn for raising pigs and they also use the barn for storage. Protected by four lightning rods, it’s in excellent condition.

Helen told us that they still own 100 acres land (I inserted corn stalks into the foreground) and that they are looking forward to earning that exclusive Ohio farm designation of being a bicentennial. Only a few decades away …

“Greenery”

Most artists don’t like to use the color green, since its nuances pose problems in mixing the right shades. However, as a landscape artist, I’ve found the color green to be wonderful – one with many values that, if used properly, can enhance any painting.

The roofs of these three barns exhibit not only different greens but a light violet, an off-white, and a bit of pink, efforts by their new owners to patch the roof. As the Achilles heel of any old barn, the roof must be maintained since, if it leaks, beams will rot, leading to an eventual collapse. I decided to give the owners, Jason and Sarah Tuente, a break – by painting the roofs in solid shades of mint green, which they were originally.

Behind the gambrel-roofed barn, the star of this show, trees were beginning to show their autumn colors and, on the right side and nearer the farmhouse, more trees were still covered with their leaves. Lots of greenery … but hardly boring.

Most artists don’t like to use the color green, since its nuances pose problems in mixing the right shades. However, as a landscape artist, I’ve found the color green to be wonderful – one with many values that, if used properly, can enhance any painting.

The roofs of these three barns exhibit not only different greens but a light violet, an off-white, and a bit of pink, efforts by their new owners to patch the roof. As the Achilles heel of any old barn, the roof must be maintained since, if it leaks, beams will rot, leading to an eventual collapse. I decided to give the owners, Jason and Sarah Tuente, a break – by painting the roofs in solid shades of mint green, which they were originally.

Behind the gambrel-roofed barn, the star of this show, trees were beginning to show their autumn colors and, on the right side and nearer the farmhouse, more trees were still covered with their leaves. Lots of greenery … but hardly boring.

“Preserved”

Owner Kevin Smail, grandson of Willis Bailer, who bought this 320-acre farm at an auction in 1949, was kind enough to allow his barn complex to be captured … but on one condition. He wasn’t happy that the barn was deteriorating and wanted the painting to reflect its former glory. I was happy to oblige.

I’m glad he decided to volunteer his barn, which is covered with rare orange clay tile, only the third barn I’ve seen with this distinctive roof. There’s one more in Shelby County – the Lotz barn – and yet another in adjacent Mercer County. Like slate – much more common and prevalent from the 1880s to the 1920s, especially in northern and eastern Ohio – the tile roof cost much more than one with wooden shingles. However, in the case of this barn, probably built in the early 1900s, the farmer’s investment has paid off: the roof is still intact.

Next to the gambrel roofed barn stands a more recent one with a gothic arched roof, a later design, one aimed at increasing space in the haymow. Further away is an attractive farmhouse, which also had been added to over the years.

It’s expensive to maintain an old barn, which not many people understand. And, if the owner puts a lot of cash into one, what does he have? An old barn … which, unfortunately, is too small for modern farm machinery. Regardless, even though the history of this farmstead may remain unknown, its memory remains in this painting – with its impressive orange tile roof leading the way, preserved and not forgotten.

Owner Kevin Smail, grandson of Willis Bailer, who bought this 320-acre farm at an auction in 1949, was kind enough to allow his barn complex to be captured … but on one condition. He wasn’t happy that the barn was deteriorating and wanted the painting to reflect its former glory. I was happy to oblige.

I’m glad he decided to volunteer his barn, which is covered with rare orange clay tile, only the third barn I’ve seen with this distinctive roof. There’s one more in Shelby County – the Lotz barn – and yet another in adjacent Mercer County. Like slate – much more common and prevalent from the 1880s to the 1920s, especially in northern and eastern Ohio – the tile roof cost much more than one with wooden shingles. However, in the case of this barn, probably built in the early 1900s, the farmer’s investment has paid off: the roof is still intact.

Next to the gambrel roofed barn stands a more recent one with a gothic arched roof, a later design, one aimed at increasing space in the haymow. Further away is an attractive farmhouse, which also had been added to over the years.

It’s expensive to maintain an old barn, which not many people understand. And, if the owner puts a lot of cash into one, what does he have? An old barn … which, unfortunately, is too small for modern farm machinery. Regardless, even though the history of this farmstead may remain unknown, its memory remains in this painting – with its impressive orange tile roof leading the way, preserved and not forgotten.

“The Geis Gem”

This L-shaped barn sits on 80 acres of land purchased in 1938 and is believed to have been built in the 1920’s. The third generation of the Geis family now owns it.