THE OHIO BARN PROJECT

Paintings Listed by Ohio County - A-C

ADAMS

"Eight Generations"

Ironically, the oldest farm in Ohio is one of the most difficult to find. I followed my car’s GPS, which led me down rural Adams County roads, past a drive signposted to an old farm open to the public for “Pioneer Days.” But that wasn’t the one I wanted. So, I kept going and heard the message from my GPS lady that I had arrived at my destination. An unmarked road, leading up a hill, was my only option; so I turned up the hill and pulled around a farmhouse where I met two of the Smileys. One was the farm’s owner, John Smiley, and the other was his son James, the eighth generation of Smileys. James has two sons, who represent generation number nine. Wow! On the map, this road is named “Smiley Road.” In reality it is unmarked.

I sat on the porch and chatted with John, the seventh generation of his family. He had just returned from a tractor pull, a competition to see who has the strongest tractor. He won third place, good for ninety bucks, more than covering his $20 entry. “It beats farming,” he joked. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Ironically, the oldest farm in Ohio is one of the most difficult to find. I followed my car’s GPS, which led me down rural Adams County roads, past a drive signposted to an old farm open to the public for “Pioneer Days.” But that wasn’t the one I wanted. So, I kept going and heard the message from my GPS lady that I had arrived at my destination. An unmarked road, leading up a hill, was my only option; so I turned up the hill and pulled around a farmhouse where I met two of the Smileys. One was the farm’s owner, John Smiley, and the other was his son James, the eighth generation of Smileys. James has two sons, who represent generation number nine. Wow! On the map, this road is named “Smiley Road.” In reality it is unmarked.

I sat on the porch and chatted with John, the seventh generation of his family. He had just returned from a tractor pull, a competition to see who has the strongest tractor. He won third place, good for ninety bucks, more than covering his $20 entry. “It beats farming,” he joked. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

ALLEN

“The Confederated Bachelor Union”

This remarkable barn was another reason I wanted to come to Allen County. I had seen a photo of it online and wanted to see it in person. So I did – in the spring of 2016 – with the help of Rheuben, and with some advice from Darlene Montooth, whose great-grandfather, a Roberts, had emigrated from Wales. The barn, not only an Ohio gem, is also a national treasure. Sadly, it falls apart a little more each year, as a visitor noted a few years ago.

The little town of Allen County’s Gomer is Welsh. Names such as Roberts, Thomas, Williams, Nicholas, and Jones were some of Gomer’s early founders. These names, essentially first names – Robert, William, Nicholas, and John (Jones) – stem back in history to when the English imposed taxation on the Welsh and demanded surnames to keep track of taxpayers. With no love for the English – which persists in modern Wales – the Welsh cleverly used their first name as their surname. Hence, Robert Roberts, William Williams, and John Jones. This presented a problem for Welsh recruits in World War I. There were a lot of John Joneses and William Williamses. So the British government labeled them by numbers, such as John Jones, number 24. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This remarkable barn was another reason I wanted to come to Allen County. I had seen a photo of it online and wanted to see it in person. So I did – in the spring of 2016 – with the help of Rheuben, and with some advice from Darlene Montooth, whose great-grandfather, a Roberts, had emigrated from Wales. The barn, not only an Ohio gem, is also a national treasure. Sadly, it falls apart a little more each year, as a visitor noted a few years ago.

The little town of Allen County’s Gomer is Welsh. Names such as Roberts, Thomas, Williams, Nicholas, and Jones were some of Gomer’s early founders. These names, essentially first names – Robert, William, Nicholas, and John (Jones) – stem back in history to when the English imposed taxation on the Welsh and demanded surnames to keep track of taxpayers. With no love for the English – which persists in modern Wales – the Welsh cleverly used their first name as their surname. Hence, Robert Roberts, William Williams, and John Jones. This presented a problem for Welsh recruits in World War I. There were a lot of John Joneses and William Williamses. So the British government labeled them by numbers, such as John Jones, number 24. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

ASHLAND

“Daniel’s Dream”

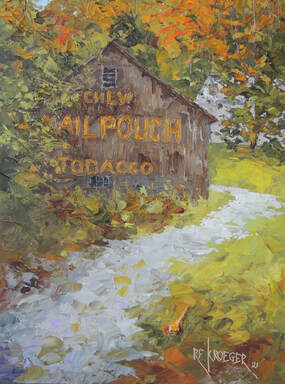

A few years earlier I thought I’d found a barn to represent Ashland County – an old, deteriorating Mail Pouch beauty, part of the Wolf Creek Grist Mill property. I noticed it while driving on Route 3 on my way to a wedding in Canton but didn’t have time to stop. Afterwards, I tried to make contact but the owner wasn’t interested. So I looked for another and, after a newspaper article described my barn project, George Gilmore contacted me about his barn and its story, another Ohio gem. Thanks, Jessica!

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press..

A few years earlier I thought I’d found a barn to represent Ashland County – an old, deteriorating Mail Pouch beauty, part of the Wolf Creek Grist Mill property. I noticed it while driving on Route 3 on my way to a wedding in Canton but didn’t have time to stop. Afterwards, I tried to make contact but the owner wasn’t interested. So I looked for another and, after a newspaper article described my barn project, George Gilmore contacted me about his barn and its story, another Ohio gem. Thanks, Jessica!

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press..

“Kenny’s Kingdom”

I decided to paint this barn twice – once with a close-up foreground of colorful autumn weeds and another with a path leading to the barn, which it may have done in the 19th century. Barn scout Kenny Libben rented it and the circa 1861 farmhouse from 2013 and purchased it four years later.

Though it sits on only three acres, the barn has character. It’s one of those rare barns that still has beams of the long-forgotten chestnut as well as the favorite wood of pioneers for timber framing – white oak, strong as steel and insect resistant. Whoever built this one – circa 1860-1880 – knew his craft. The founder remains unknown but the Thoms family owned it for many decades.

Though a few of the beams are hand-hewn, most are saw-cut, confirming what Kenny said about a sawmill nearby. Even though paying a miller to cut the beams cost money, it was faster and easier than hand-hewing them. As typical of timber-framing, the beams are connected with mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs. The original wood shake roof is in excellent condition, thanks to an interesting metal covering, probably put on in the early 1900s. For such a metal roof to last a century, it must be special.

However, the farmstead was abandoned during the Great Depression, not unusual for farms in those bleak years, and even today it needs some restoration, which Kenny plans to accomplish. After all, it’s his kingdom … and he gets free natural gas, thanks to his grandfather, who drilled gas wells here.

I decided to paint this barn twice – once with a close-up foreground of colorful autumn weeds and another with a path leading to the barn, which it may have done in the 19th century. Barn scout Kenny Libben rented it and the circa 1861 farmhouse from 2013 and purchased it four years later.

Though it sits on only three acres, the barn has character. It’s one of those rare barns that still has beams of the long-forgotten chestnut as well as the favorite wood of pioneers for timber framing – white oak, strong as steel and insect resistant. Whoever built this one – circa 1860-1880 – knew his craft. The founder remains unknown but the Thoms family owned it for many decades.

Though a few of the beams are hand-hewn, most are saw-cut, confirming what Kenny said about a sawmill nearby. Even though paying a miller to cut the beams cost money, it was faster and easier than hand-hewing them. As typical of timber-framing, the beams are connected with mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs. The original wood shake roof is in excellent condition, thanks to an interesting metal covering, probably put on in the early 1900s. For such a metal roof to last a century, it must be special.

However, the farmstead was abandoned during the Great Depression, not unusual for farms in those bleak years, and even today it needs some restoration, which Kenny plans to accomplish. After all, it’s his kingdom … and he gets free natural gas, thanks to his grandfather, who drilled gas wells here.

“Gem Hill Dairy’s Gem”

Located in Ashland County’s Maple Heights area, this farmstead is a working dairy, besides being a delicious composition. It would interest any artist or photographer – a wavy road cascading down a hill and past a corn field, an old barn surrounded by outbuildings, a towering brownish silo, and a forest in the distance.

Barn scout Kenny explained that this was Gem Hill Dairy. I’d have to agree: the composition was indeed a gem.

Located in Ashland County’s Maple Heights area, this farmstead is a working dairy, besides being a delicious composition. It would interest any artist or photographer – a wavy road cascading down a hill and past a corn field, an old barn surrounded by outbuildings, a towering brownish silo, and a forest in the distance.

Barn scout Kenny explained that this was Gem Hill Dairy. I’d have to agree: the composition was indeed a gem.

ASHTABULA

"The Octagonal"

One of Ohio's last remaining round barns, this one won't last forever. Actually, the barn isn't truly round; it has eight sides, earning the title, "The Octagonal." Orange day lilies complement the rustic timbers of the old fellow. It tells a good story about early Ohio history.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

One of Ohio's last remaining round barns, this one won't last forever. Actually, the barn isn't truly round; it has eight sides, earning the title, "The Octagonal." Orange day lilies complement the rustic timbers of the old fellow. It tells a good story about early Ohio history.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

ATHENS

“Flight School”

A sign titled “Red Bird Ranch” makes it hard to miss this large red bank barn, sitting on a rise adjacent to State Route 329. A large, ornate cupola, its red paint fading to gray, sits on the roof and a tall silo stands behind it. Glenn K. Lackey, co-owner of the barn with his brothers Ryan and Keith and his mother Lola Mae, told me that his dad purchased the farm in 1973. These days they farm 900 acres, growing soybeans, corn, and hay and raising 200 head of Black Angus cattle, housing them in some of their many barns. Though this red barn formerly was home to a flock of sheep, today it’s used for storage. But the farm goes back much farther since the current farmhouse traces to 1844, probably built after the farmer became established.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

A sign titled “Red Bird Ranch” makes it hard to miss this large red bank barn, sitting on a rise adjacent to State Route 329. A large, ornate cupola, its red paint fading to gray, sits on the roof and a tall silo stands behind it. Glenn K. Lackey, co-owner of the barn with his brothers Ryan and Keith and his mother Lola Mae, told me that his dad purchased the farm in 1973. These days they farm 900 acres, growing soybeans, corn, and hay and raising 200 head of Black Angus cattle, housing them in some of their many barns. Though this red barn formerly was home to a flock of sheep, today it’s used for storage. But the farm goes back much farther since the current farmhouse traces to 1844, probably built after the farmer became established.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

AUGLAIZE

“Magnificent Manchester”

This iconic round barn is one of Ohio’s most photographed and painted, and rightfully so. The dark roof, contrasting with deep red siding and white trim, provides a striking composition, which many artists have been drawn to capture, as evidenced by the hundreds of images found in a Google search. Even though George Washington designed and built a sixteen-sided threshing barn at his farm in Virginia in 1793 and the Shakers built the first truly round barn in Massachusetts in 1826, this type of barn did not catch on until the late 1800s. An article, The Economy of a Round Dairy Barn, written by Wilbur Frazer and published by the University of Illinois in 1908, described the benefits of a round barn: more efficient housing for cows, time savings in feeding, a protected silo, and easier silage distribution. The article also inferred that construction of a round barn was less expensive than a rectangular one and that “progressive” farmers should consider such a barn. The opposite was true – circular barns were more expensive than rectangular ones and the “progressive” farmers were usually only the wealthy ones. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This iconic round barn is one of Ohio’s most photographed and painted, and rightfully so. The dark roof, contrasting with deep red siding and white trim, provides a striking composition, which many artists have been drawn to capture, as evidenced by the hundreds of images found in a Google search. Even though George Washington designed and built a sixteen-sided threshing barn at his farm in Virginia in 1793 and the Shakers built the first truly round barn in Massachusetts in 1826, this type of barn did not catch on until the late 1800s. An article, The Economy of a Round Dairy Barn, written by Wilbur Frazer and published by the University of Illinois in 1908, described the benefits of a round barn: more efficient housing for cows, time savings in feeding, a protected silo, and easier silage distribution. The article also inferred that construction of a round barn was less expensive than a rectangular one and that “progressive” farmers should consider such a barn. The opposite was true – circular barns were more expensive than rectangular ones and the “progressive” farmers were usually only the wealthy ones. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Surprise”

Thanks to my Google Alerts program, I discovered a story about this incredibly rare barn near Minster, Ohio, only two miles from the Mercer County line and another two miles from the Shelby County line. Leslie Gartrell wrote an article in Celina’s Daily Standard newspaper about it, prompted by a call to the newspaper from a neighbor of the barn owners, Gary and Joanna Homan. Their neighbor explained that a large barn was being taken down and it “looked like it had a log cabin inside of it.” Immediately, the newspaper dispatched photographer Dan Melograna, who captured several images of the partially dismantled barn skeleton, clearly showing the log barn. Newspapers in rural counties respect their old barns - especially ones like this one, a double-pen log barn. Few have survived. This one came down in the summer of 2021. Gary told me that the log beams filled an entire semi-trailer.

One of these double-pen log barns, beautifully preserved in the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency historical site near Piqua, only 20 miles away, was built in 1808 by Colonel John Johnston. Cleverly, instead of cutting down trees and hand hewing them, he took the logs from one of General Anthony Wayne’s forts, built as he marched northwards to fight the Indians in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Johnston marched with him and was in charge of supplies.

Usually, Ohio pioneers, upon taking possession of land, would build a log home to live in and sometimes, weather permitting, would build a simple log barn, about 20 by 20 feet. Occasionally, if their wallets allowed, they’d build a double-pen log barn, sometimes even living in one of the pens and housing the livestock and hay in the other. In Ireland, this was called a byre and was common on Eire’s impoverished western side. Gary wrote that the breezeway between the two log pens was large enough for a wagon full of hay. The livestock were probably housed in the other pen.

Records show that John Henry Schulte bought the property, 40 acres, in 1835, and he likely built the log barn about that time. While there may have been other single- and double-pen log barns in the area, Schulte may also have visited the Johnston farm since it was well-known at the time. Until 1829 Colonel Johnston ran the government Indian Agency in Piqua. Fourteen years later, the Wyandots became the last Indian tribe to be removed from Ohio.

However, as farmers became more prosperous, they needed larger barns – for more livestock, feed, and crop storage. Usually they dismantled the original log barn, often repurposing the hand-hewn beams when they built a larger barn, but sometimes they’d simply keep the log barn and build around it, as happened in the Homan barn. Gary explained that John Schulte deeded the farm to his son Henry in 1874, which might have been about when the larger barn was built. Sons often have new ideas and their ownership can lead to changes. The new timber had been cut in a sawmill, which may have been close by. While dismantling, workers found hay hooks and a die cast pulley system. The pulleys were dated 1887.

The village of Minster, population 2,800 – where this barn was located – also presents another piece of Ohio history. The city’s boundaries include both Auglaize and Shelby counties, even though the village was founded as part of Mercer County. It was given to Auglaize County, when that county was founded in 1848. Originally named Stallostown, after its founder Francis Stallo, who established it in 1832, the village changed its name to Minster four years later, mainly because of an influx of Germans.

Many of these immigrated from Munster, Westphalia, Germany, a heavily Catholic region, and, after arriving in Cincinnati, they boarded boats on the Miami and Erie Canal. After changing the name of the village in 1836, they also re-named some of the streets – to Berlin, Vienna, and Oldenburg.

When I met the Gary, he told me that the barn was on its last legs, which made it difficult to maintain, a problem common to many Ohio families with an old barn that has outgrown its usefulness. So, after searching for a year, he hired an Amish crew to dismantle it and repurpose it somewhere in northeastern Ohio. Gary showed me the footprint of where the barn stood, not far from State Route 119, most likely only a dirt trail when the barn was built. He said that, when they were raising 100 calves in individual pens, the old barn did not provide adequate ventilation, despite opening the doors and using many fans. So, despite the fact that the log barn was in good condition, the rest of the “newer” barn was beyond repair.

He also showed me a postcard, postmarked July 28, 1934, which they found in the house and which revealed another page of the past in early Ohio farming. Addressed to Henry Baumer, Route 1, Minster, the card announced a meeting, sponsored by the Equity Union Creamery, to be held at the Jackson School on the evening of July 31. It requested that Mr. Bauman and his family attend “in order that the farmers may intelligently approach the important problems that have come up during these trying times, and be able to approach them in an organized manner, for the purpose of defending his industry and getting a reasonable price for his products … Delay in approaching these problems intelligently will be disastrous … The creamery will furnish the ice cream.”

Although during the Great Depression, suicides and bread lines were common in the big cities, most small Ohio farmers survived well, growing their own food and living simply. One 99-year-old, who shared an upstairs bedroom with her seven sisters on a farm in Highland County (the parents got the room on the first floor), when I posed the question about these dark days, simply said, “What depression?” However, some farmers, who had expanded their production and had taken on lending notes and mortgages, lost their farms to bankers. With demand down for agricultural goods, farm prices plummeted. Indeed, these were trying times, as illustrated in this effort to boost dairy prices.

Today, Gary farms and Joanna works for her family’s business. After buying the farm and its six acres in 2012, they purchased the adjoining 80 acres, which was part of the original farm. He raises corn, soybeans, hay, and wheat on this farm – as well as on an additional 110 acres. The corn and hay are used to feed beef cattle and the wheat and soybeans are sold at a local grain elevator. He’s an active farmer.

Before I left, Gary showed me the original barn footprint and gave me some barn siding for the frame. Yes, the barn’s gone now but it will be preserved forever in this essay and painting, framed in the barn’s own wood, a tribute to this rare double-pen log barn and the remarkable postcard of the Great Depression, both real surprises.

Thanks to my Google Alerts program, I discovered a story about this incredibly rare barn near Minster, Ohio, only two miles from the Mercer County line and another two miles from the Shelby County line. Leslie Gartrell wrote an article in Celina’s Daily Standard newspaper about it, prompted by a call to the newspaper from a neighbor of the barn owners, Gary and Joanna Homan. Their neighbor explained that a large barn was being taken down and it “looked like it had a log cabin inside of it.” Immediately, the newspaper dispatched photographer Dan Melograna, who captured several images of the partially dismantled barn skeleton, clearly showing the log barn. Newspapers in rural counties respect their old barns - especially ones like this one, a double-pen log barn. Few have survived. This one came down in the summer of 2021. Gary told me that the log beams filled an entire semi-trailer.

One of these double-pen log barns, beautifully preserved in the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency historical site near Piqua, only 20 miles away, was built in 1808 by Colonel John Johnston. Cleverly, instead of cutting down trees and hand hewing them, he took the logs from one of General Anthony Wayne’s forts, built as he marched northwards to fight the Indians in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Johnston marched with him and was in charge of supplies.

Usually, Ohio pioneers, upon taking possession of land, would build a log home to live in and sometimes, weather permitting, would build a simple log barn, about 20 by 20 feet. Occasionally, if their wallets allowed, they’d build a double-pen log barn, sometimes even living in one of the pens and housing the livestock and hay in the other. In Ireland, this was called a byre and was common on Eire’s impoverished western side. Gary wrote that the breezeway between the two log pens was large enough for a wagon full of hay. The livestock were probably housed in the other pen.

Records show that John Henry Schulte bought the property, 40 acres, in 1835, and he likely built the log barn about that time. While there may have been other single- and double-pen log barns in the area, Schulte may also have visited the Johnston farm since it was well-known at the time. Until 1829 Colonel Johnston ran the government Indian Agency in Piqua. Fourteen years later, the Wyandots became the last Indian tribe to be removed from Ohio.

However, as farmers became more prosperous, they needed larger barns – for more livestock, feed, and crop storage. Usually they dismantled the original log barn, often repurposing the hand-hewn beams when they built a larger barn, but sometimes they’d simply keep the log barn and build around it, as happened in the Homan barn. Gary explained that John Schulte deeded the farm to his son Henry in 1874, which might have been about when the larger barn was built. Sons often have new ideas and their ownership can lead to changes. The new timber had been cut in a sawmill, which may have been close by. While dismantling, workers found hay hooks and a die cast pulley system. The pulleys were dated 1887.

The village of Minster, population 2,800 – where this barn was located – also presents another piece of Ohio history. The city’s boundaries include both Auglaize and Shelby counties, even though the village was founded as part of Mercer County. It was given to Auglaize County, when that county was founded in 1848. Originally named Stallostown, after its founder Francis Stallo, who established it in 1832, the village changed its name to Minster four years later, mainly because of an influx of Germans.

Many of these immigrated from Munster, Westphalia, Germany, a heavily Catholic region, and, after arriving in Cincinnati, they boarded boats on the Miami and Erie Canal. After changing the name of the village in 1836, they also re-named some of the streets – to Berlin, Vienna, and Oldenburg.

When I met the Gary, he told me that the barn was on its last legs, which made it difficult to maintain, a problem common to many Ohio families with an old barn that has outgrown its usefulness. So, after searching for a year, he hired an Amish crew to dismantle it and repurpose it somewhere in northeastern Ohio. Gary showed me the footprint of where the barn stood, not far from State Route 119, most likely only a dirt trail when the barn was built. He said that, when they were raising 100 calves in individual pens, the old barn did not provide adequate ventilation, despite opening the doors and using many fans. So, despite the fact that the log barn was in good condition, the rest of the “newer” barn was beyond repair.

He also showed me a postcard, postmarked July 28, 1934, which they found in the house and which revealed another page of the past in early Ohio farming. Addressed to Henry Baumer, Route 1, Minster, the card announced a meeting, sponsored by the Equity Union Creamery, to be held at the Jackson School on the evening of July 31. It requested that Mr. Bauman and his family attend “in order that the farmers may intelligently approach the important problems that have come up during these trying times, and be able to approach them in an organized manner, for the purpose of defending his industry and getting a reasonable price for his products … Delay in approaching these problems intelligently will be disastrous … The creamery will furnish the ice cream.”

Although during the Great Depression, suicides and bread lines were common in the big cities, most small Ohio farmers survived well, growing their own food and living simply. One 99-year-old, who shared an upstairs bedroom with her seven sisters on a farm in Highland County (the parents got the room on the first floor), when I posed the question about these dark days, simply said, “What depression?” However, some farmers, who had expanded their production and had taken on lending notes and mortgages, lost their farms to bankers. With demand down for agricultural goods, farm prices plummeted. Indeed, these were trying times, as illustrated in this effort to boost dairy prices.

Today, Gary farms and Joanna works for her family’s business. After buying the farm and its six acres in 2012, they purchased the adjoining 80 acres, which was part of the original farm. He raises corn, soybeans, hay, and wheat on this farm – as well as on an additional 110 acres. The corn and hay are used to feed beef cattle and the wheat and soybeans are sold at a local grain elevator. He’s an active farmer.

Before I left, Gary showed me the original barn footprint and gave me some barn siding for the frame. Yes, the barn’s gone now but it will be preserved forever in this essay and painting, framed in the barn’s own wood, a tribute to this rare double-pen log barn and the remarkable postcard of the Great Depression, both real surprises.

BELMONT

“Bentley Sweet”

In my quest to find at least one barn in each of Ohio’s 88 counties and on my whirlwind trip through ten of them along eastern Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, I visited Barkcamp State Park in Belmont County – not far from I-70. From reading Harley’s Warrick’s book, I knew that there was an old barn in this park, one painted with his iconic Mail Pouch logo. And, I found it without too much difficulty. The barn traces back to the 1800s when it was built by Solomon Bentley, a sort of Johnny Appleseed – an orchardman famous for planting apple trees. One variety of apples he marketed was called Bentley Sweet. An 1866 report of the Ohio Department of Agriculture called the apple “a showy apple of medium quality” and said that its crop was large that year. Also, the 1917 Annual Report of the Ohio State Horticultural Society – thank you, Google – described a harvest of nearly 2,000 bushels of this apple from the society’s test station – 135 trees in the plot – on the farm of S.E. Hare in Lamira, Belmont County. The article mentioned that the tree was subject to bitter rot, which had caused the loss of 85 bushels. Apparently this disease may have led to the demise of this tree. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

In my quest to find at least one barn in each of Ohio’s 88 counties and on my whirlwind trip through ten of them along eastern Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, I visited Barkcamp State Park in Belmont County – not far from I-70. From reading Harley’s Warrick’s book, I knew that there was an old barn in this park, one painted with his iconic Mail Pouch logo. And, I found it without too much difficulty. The barn traces back to the 1800s when it was built by Solomon Bentley, a sort of Johnny Appleseed – an orchardman famous for planting apple trees. One variety of apples he marketed was called Bentley Sweet. An 1866 report of the Ohio Department of Agriculture called the apple “a showy apple of medium quality” and said that its crop was large that year. Also, the 1917 Annual Report of the Ohio State Horticultural Society – thank you, Google – described a harvest of nearly 2,000 bushels of this apple from the society’s test station – 135 trees in the plot – on the farm of S.E. Hare in Lamira, Belmont County. The article mentioned that the tree was subject to bitter rot, which had caused the loss of 85 bushels. Apparently this disease may have led to the demise of this tree. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

BROWN

“Dr. Tyler’s Horses”

Try to imagine the country doctor, traveling in a buggy pulled by a horse, making house calls, delivering babies in farmhouses. Such was the life of one Dr. Tyler in the 1920s, a tradition continued by his son, also a Dr. Tyler. The younger Dr. Tyler had an entrepreneurial bent, learning the banking business, and increasing the size of this farm that he acquired in the 1940s till it grew to nearly 1,000 acres and included 18 barns. Dr. Tyler also had a thing for horses.

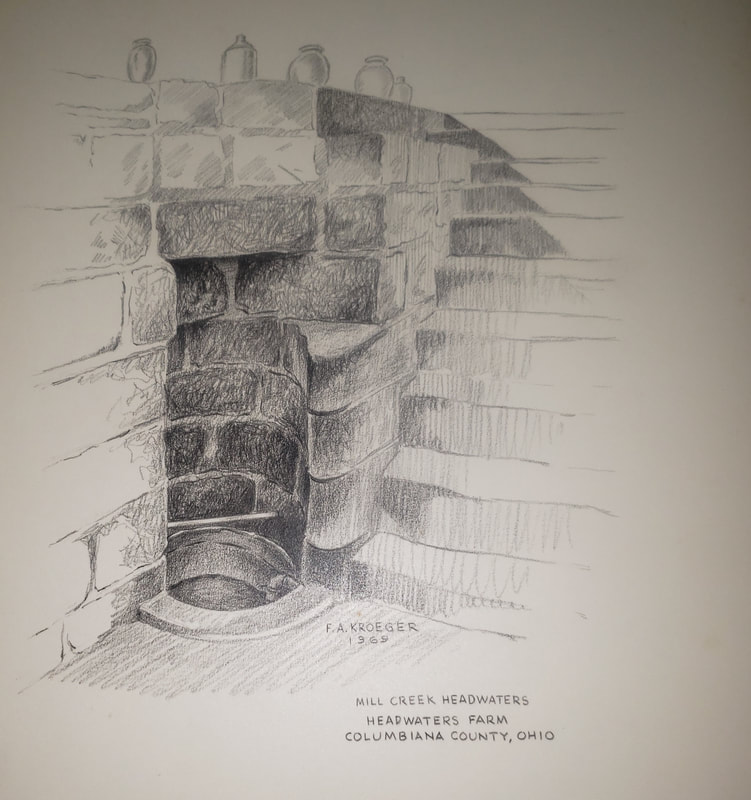

In the spring of 2017 Brian showed me the doctor’s horse barn, a rectangular structure with 25 stalls for the many horses he collected. That day several large cows owned the turf; no horses showed up. The stalls were empty. Next to the barn sits the foundation of a blacksmith’s shop and forge, sheds with fireplaces, a spring house, and a ring for training the horses. He spared no expense in building this complex. It must have given him much enjoyment. And, with horse sales, perhaps more income as well.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Try to imagine the country doctor, traveling in a buggy pulled by a horse, making house calls, delivering babies in farmhouses. Such was the life of one Dr. Tyler in the 1920s, a tradition continued by his son, also a Dr. Tyler. The younger Dr. Tyler had an entrepreneurial bent, learning the banking business, and increasing the size of this farm that he acquired in the 1940s till it grew to nearly 1,000 acres and included 18 barns. Dr. Tyler also had a thing for horses.

In the spring of 2017 Brian showed me the doctor’s horse barn, a rectangular structure with 25 stalls for the many horses he collected. That day several large cows owned the turf; no horses showed up. The stalls were empty. Next to the barn sits the foundation of a blacksmith’s shop and forge, sheds with fireplaces, a spring house, and a ring for training the horses. He spared no expense in building this complex. It must have given him much enjoyment. And, with horse sales, perhaps more income as well.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

BUTLER

“The Beer Baron’s Barn”

It’s old – as the 1881 date on the roof testifies – and it was built by Gottlieb Muhlhauser, whose name also graces the slate roof. This barn, rescued from dismantling by West Chester Township, introduces a colorful page of Ohio history – the breweries of Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine and their farms in Butler County.

The story begins with Conrad Windisch, born in Bavaria in 1825, who worked in his father’s brewery in Germany before he immigrated to America in 1849. After arriving, he worked in breweries in Pittsburgh and St. Louis. When he moved to Cincinnati, he became partners with Christian Moerlein, who had established a brewery in 1853. Windisch sold his interest to Moerlein 13 years later in 1866.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

It’s old – as the 1881 date on the roof testifies – and it was built by Gottlieb Muhlhauser, whose name also graces the slate roof. This barn, rescued from dismantling by West Chester Township, introduces a colorful page of Ohio history – the breweries of Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine and their farms in Butler County.

The story begins with Conrad Windisch, born in Bavaria in 1825, who worked in his father’s brewery in Germany before he immigrated to America in 1849. After arriving, he worked in breweries in Pittsburgh and St. Louis. When he moved to Cincinnati, he became partners with Christian Moerlein, who had established a brewery in 1853. Windisch sold his interest to Moerlein 13 years later in 1866.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

CARROLL

“Serendipity”

Webster defines serendipity as the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way, which is exactly what happened when I passed this magnificent scene in Carroll County on an early late September morning in 2018.

Before daylight I began my “solo” tour of the barns along Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, leaving Mahoning County – after a fundraiser for SMARTS – and dropping off a commissioned painting in Columbiana County. At first light I stopped at the sight of a Mail Pouch barn, deteriorating, boards missing, and took a few minutes to sketch it even though I’ve already done several barns in that county.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Webster defines serendipity as the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way, which is exactly what happened when I passed this magnificent scene in Carroll County on an early late September morning in 2018.

Before daylight I began my “solo” tour of the barns along Ohio’s Appalachian Plateau, leaving Mahoning County – after a fundraiser for SMARTS – and dropping off a commissioned painting in Columbiana County. At first light I stopped at the sight of a Mail Pouch barn, deteriorating, boards missing, and took a few minutes to sketch it even though I’ve already done several barns in that county.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

CHAMPAIGN

“Black Bart Barn”

It’s hard to miss this old barn complex, painted a dead black, as it sits in plain view at the intersection of routes 68 and 296, a few miles from Urbana. As barn scout Ken and I looked at it from the road, the first thought that came was that of Black Bart, the imaginary villain in A Christmas Story, one of America’s favorite movies. In the film, the quiet nine-year-old Ralphie yearns dearly for a BB gun, but his mom, dad, and even Santa warn him repeatedly, “You’ll shoot your eye out!” Undeterred, Ralphie daydreams and imagines a gang of hoodlums, led by Black Bart, who was about to rob the family’s house. Enter Ralphie and his BB gun. The gang took flight but Ralphie shot four of them with his gun. Only Black Bart escaped. Well, this old black barn somehow shook that memory loose.

Black Barn was, in fact, an outlaw in the 19th-century Wild West, though he didn’t start out that way. Since this story is a long one, I didn't post it, but it may find a place in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

It’s hard to miss this old barn complex, painted a dead black, as it sits in plain view at the intersection of routes 68 and 296, a few miles from Urbana. As barn scout Ken and I looked at it from the road, the first thought that came was that of Black Bart, the imaginary villain in A Christmas Story, one of America’s favorite movies. In the film, the quiet nine-year-old Ralphie yearns dearly for a BB gun, but his mom, dad, and even Santa warn him repeatedly, “You’ll shoot your eye out!” Undeterred, Ralphie daydreams and imagines a gang of hoodlums, led by Black Bart, who was about to rob the family’s house. Enter Ralphie and his BB gun. The gang took flight but Ralphie shot four of them with his gun. Only Black Bart escaped. Well, this old black barn somehow shook that memory loose.

Black Barn was, in fact, an outlaw in the 19th-century Wild West, though he didn’t start out that way. Since this story is a long one, I didn't post it, but it may find a place in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

“Green Gothic”

As barn scout Ken and I drove along Route 68, not far from the county seat of Urbana, we noticed this interesting barn with three aging silos towering behind it. It was intriguing, in part, because of its semi-gothic arch roof and its green color.

Though we didn’t get a chance to visit it or speak to the owner, apparently, the farm had become so prosperous that the farmer added a rectangular extension for livestock, evidenced by multiple windows, which provided much needed light for the animals. It’s hard to determine the sequence of silo construction, all concrete. Was a small one built, followed by another small one, and then by the largest? Or was it the other way around. Was the barn built in the challenging years of the 1920s, just as difficult for farmers as the Great Depression, only 10 years away, was for all of America.

Another curious aspect of this farmstead is the gothic arched roof. Though this roof design, which originated in Michigan, first occurred in the late 19th-century, it did not become popular until the early 1900s, when it began to overtake the traditional gambrel roof. Earlier, most barns featured a simple gable roof, followed by the gambrel style, designed to provide more storage for hay and grain. The gothic roof continued that progression, offering even more storage space.

One pioneer in this design was Ohioan John L. Shawver of Bellefontaine, who advocated a system of laminated straight boards, a construction method that was not only cheaper and faster than traditional timber framing but also eliminated vertical posts, making hay storage easier. He introduced the Shawver truss in 1904 and built many barns with his design.

Eventually, gothic arch trusses could be built with long boards bent into a curved shape, adding to their popularity. In fact, a 1916 edition of the Idaho Farmer agricultural journal predicted that the Gothic-arch roof “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy barns.” In 1918 Sears and Roebuck featured the gothic arch roof on the front and back cover of its prefabricated barn catalog, The Book of Barns - Honor-Bilt-Already Cut. It was their biggest seller.

The Great Depression of the 1930s slowed barn building and, after World War II, barn construction changed, decreasing the need for the gothic arch roof. By the 1960s hay bales were covered and stored on the ground, relegating this design to another page in farm history. However, on any typical drive in the countryside, visitors will see more barns with gable and gambrel roofs than those with a gothic design, making this one, especially with its green color, even more special.

As barn scout Ken and I drove along Route 68, not far from the county seat of Urbana, we noticed this interesting barn with three aging silos towering behind it. It was intriguing, in part, because of its semi-gothic arch roof and its green color.

Though we didn’t get a chance to visit it or speak to the owner, apparently, the farm had become so prosperous that the farmer added a rectangular extension for livestock, evidenced by multiple windows, which provided much needed light for the animals. It’s hard to determine the sequence of silo construction, all concrete. Was a small one built, followed by another small one, and then by the largest? Or was it the other way around. Was the barn built in the challenging years of the 1920s, just as difficult for farmers as the Great Depression, only 10 years away, was for all of America.

Another curious aspect of this farmstead is the gothic arched roof. Though this roof design, which originated in Michigan, first occurred in the late 19th-century, it did not become popular until the early 1900s, when it began to overtake the traditional gambrel roof. Earlier, most barns featured a simple gable roof, followed by the gambrel style, designed to provide more storage for hay and grain. The gothic roof continued that progression, offering even more storage space.

One pioneer in this design was Ohioan John L. Shawver of Bellefontaine, who advocated a system of laminated straight boards, a construction method that was not only cheaper and faster than traditional timber framing but also eliminated vertical posts, making hay storage easier. He introduced the Shawver truss in 1904 and built many barns with his design.

Eventually, gothic arch trusses could be built with long boards bent into a curved shape, adding to their popularity. In fact, a 1916 edition of the Idaho Farmer agricultural journal predicted that the Gothic-arch roof “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy barns.” In 1918 Sears and Roebuck featured the gothic arch roof on the front and back cover of its prefabricated barn catalog, The Book of Barns - Honor-Bilt-Already Cut. It was their biggest seller.

The Great Depression of the 1930s slowed barn building and, after World War II, barn construction changed, decreasing the need for the gothic arch roof. By the 1960s hay bales were covered and stored on the ground, relegating this design to another page in farm history. However, on any typical drive in the countryside, visitors will see more barns with gable and gambrel roofs than those with a gothic design, making this one, especially with its green color, even more special.

"Man Door, Millerstown-Eris Road"

Though this barn was nearly completely hidden by scrub, brush, and trees, I managed to find a quaint man door on one of its sides, just waiting to be painted. Shadows crept through and left their mark on the barn door.

Though this barn was nearly completely hidden by scrub, brush, and trees, I managed to find a quaint man door on one of its sides, just waiting to be painted. Shadows crept through and left their mark on the barn door.

“Her Last Legs”

Like another deteriorating barn in Millerstown, not far from here, this one is apparently going to be lost soon – like so many old barns in Ohio that no longer serve a purpose. Overgrown with brush and partially hidden by 10- to 20-year-old trees, its majesty has faded, though at one time it must have been a busy place, sitting next to Millerstown-Eris Road.

When it was built – probably between 1890 and 1910, the farmer was well off enough to use slate on the roof, a long-term investment, more durable than wood, but more expensive, too. Today, pieces of slate litter the ground and openings in the roof hint that interior lumber may soon be rotted by water. Like its neighbor, this barn also features a slight bank, though it’s supported by a concrete wall, not fieldstones. It also has a couple of man doors, one of which was charming enough for a painting, which may be the last memory of this old girl, definitely on her last legs.

Like another deteriorating barn in Millerstown, not far from here, this one is apparently going to be lost soon – like so many old barns in Ohio that no longer serve a purpose. Overgrown with brush and partially hidden by 10- to 20-year-old trees, its majesty has faded, though at one time it must have been a busy place, sitting next to Millerstown-Eris Road.

When it was built – probably between 1890 and 1910, the farmer was well off enough to use slate on the roof, a long-term investment, more durable than wood, but more expensive, too. Today, pieces of slate litter the ground and openings in the roof hint that interior lumber may soon be rotted by water. Like its neighbor, this barn also features a slight bank, though it’s supported by a concrete wall, not fieldstones. It also has a couple of man doors, one of which was charming enough for a painting, which may be the last memory of this old girl, definitely on her last legs.

“Forgotten”

Although it may be gone by the time this essay is published, this old barn sits on Ford Road, near the intersection with Trestle Road … and in the village of Millerstown. Platted in 1837, the community was named after landowner Casper Miller, who apparently was a man of influence in the area. A year later, a post office was opened and kept going until 1903, approximately the same time as this barn.

Built into a slight bank, the barn was probably used for many years of farming, some of it prosperous enough to warrant the farmer adding an extension. Some of its fieldstone foundation was replaced with cinder blocks, probably due to damage. Barn scout Ken and I were fortunate to visit it in April before the growth of summer foilage, which would have completely hidden the barn. Now it sits alone, surrounded by heavy undergrowth, waiting for the owner to decide what to do with it, another forgotten piece of history.

Although it may be gone by the time this essay is published, this old barn sits on Ford Road, near the intersection with Trestle Road … and in the village of Millerstown. Platted in 1837, the community was named after landowner Casper Miller, who apparently was a man of influence in the area. A year later, a post office was opened and kept going until 1903, approximately the same time as this barn.

Built into a slight bank, the barn was probably used for many years of farming, some of it prosperous enough to warrant the farmer adding an extension. Some of its fieldstone foundation was replaced with cinder blocks, probably due to damage. Barn scout Ken and I were fortunate to visit it in April before the growth of summer foilage, which would have completely hidden the barn. Now it sits alone, surrounded by heavy undergrowth, waiting for the owner to decide what to do with it, another forgotten piece of history.

“The General Store”

Most old barns have outlived their usefulness and have vanished from the rural landscape – destroyed either by strong wind, fire, general deterioration, or by dismantling. However, some are repurposed, given a new function, and survive. A growing trend shows that young folks like to get married in an old barn. Others get converted into wineries, performance venues for plays, and museums. One in Montana has become a church and one in Georgia has evolved into a mattress firm (the dairy cows, once on a level below the sales room, are now gone). This one has become a country store, a business which was much more common a century ago.

Long before the general store, tinkers provided wares and did repairs. This trade evolved from 13th-century Scotland and England and came to America with the rest of the millions of immigrants. A 19th-century newspaper in Kingston, New York, reported that a local tinker known as Brandow posted a sign on the street next to his shop that described his services, “Eny 1 wantin ena thing fixt kin got it dun t’ Brandows.” He boasted he could fix anything and, even though his skills as a tinker were well known, one person viewed him differently, “Brandow was a necessary evil. People by no means liked his manner, but had to employ him. … The tinker himself was a figure once seen, never to be forgotten … He was a large man, dressed in whatever came in handy.” This essay is too long to be posted. But, if you're driving near Urbana, please stop in!!

Most old barns have outlived their usefulness and have vanished from the rural landscape – destroyed either by strong wind, fire, general deterioration, or by dismantling. However, some are repurposed, given a new function, and survive. A growing trend shows that young folks like to get married in an old barn. Others get converted into wineries, performance venues for plays, and museums. One in Montana has become a church and one in Georgia has evolved into a mattress firm (the dairy cows, once on a level below the sales room, are now gone). This one has become a country store, a business which was much more common a century ago.

Long before the general store, tinkers provided wares and did repairs. This trade evolved from 13th-century Scotland and England and came to America with the rest of the millions of immigrants. A 19th-century newspaper in Kingston, New York, reported that a local tinker known as Brandow posted a sign on the street next to his shop that described his services, “Eny 1 wantin ena thing fixt kin got it dun t’ Brandows.” He boasted he could fix anything and, even though his skills as a tinker were well known, one person viewed him differently, “Brandow was a necessary evil. People by no means liked his manner, but had to employ him. … The tinker himself was a figure once seen, never to be forgotten … He was a large man, dressed in whatever came in handy.” This essay is too long to be posted. But, if you're driving near Urbana, please stop in!!

“Simply Stately”

Though barn scout Ken and I didn’t get the chance to visit this farmstead – at the intersection of Routes 29 and 296 – or learn much about it, the view of the old barn, its green roof and towering cement silo, was worth a painting. With a backdrop of autumn colors and a foreground of harvested corn, it was, in any artist’s eye, simply stately.

Though barn scout Ken and I didn’t get the chance to visit this farmstead – at the intersection of Routes 29 and 296 – or learn much about it, the view of the old barn, its green roof and towering cement silo, was worth a painting. With a backdrop of autumn colors and a foreground of harvested corn, it was, in any artist’s eye, simply stately.

“Fieldstone”

As barn scout Ken and I headed back to the history center – after finishing our tour – we passed by this old barn and decided to stop. Though we didn’t have time to knock on the farmhouse door, we had a pretty good look at the barn from Millerstown-Eris Road. Ken thought that the barn was being used to house beef cattle.

The old barn, built into a bank, wasn’t large, but the add-on extension was, as it cascaded down the hillside. Though it was a good composition – with trees and a farmhouse in the background – the highlight was the foundation, a colorful array of fieldstone. Most of the stones are laid on top of one another without mortar, illustrating the skill of the stonemason, whose work – now probably over a century old – shows that he was an expert in using fieldstone.

As barn scout Ken and I headed back to the history center – after finishing our tour – we passed by this old barn and decided to stop. Though we didn’t have time to knock on the farmhouse door, we had a pretty good look at the barn from Millerstown-Eris Road. Ken thought that the barn was being used to house beef cattle.

The old barn, built into a bank, wasn’t large, but the add-on extension was, as it cascaded down the hillside. Though it was a good composition – with trees and a farmhouse in the background – the highlight was the foundation, a colorful array of fieldstone. Most of the stones are laid on top of one another without mortar, illustrating the skill of the stonemason, whose work – now probably over a century old – shows that he was an expert in using fieldstone.

“The Kiss”

Mrs. Rosalie Kuss, whose surname is a German word that means kiss, told us that the farm was originally settled by the Woodruff family. Unfortunately, a tornado in 1948 blew through the farm, destroying the old barns.

This one, a large barn with a gothic arch roof, a protruding second-story entrance to the haymow, and a striking fieldstone foundation, still functions. Besides providing plenty of room for straw and hay, it houses hogs, cattle, and sheep. These days, it’s owned by the Woodruff Family Trust. But the story goes to Rosalie and her last name, which she acquired when she remarried after her first husband died.

The Kiss is an iconic sculpture by Auguste Rodin, the famous French artist, who sculpted another classic, The Thinker, both of which are displayed in the Rodin museum in Paris. The Kiss, made of marble in 1882, depicts a couple, kissing in an embrace, a piece that appeared originally as part of a group of reliefs decorating Rodin’s monumental bronze portal, The Gates of Hell, commissioned for a planned museum of art in Paris. The sculpture was originally titled Francesca da Rimini, after the 13th-century Italian noblewoman immortalized in Dante’s Inferno. After Francesca fell in love with her husband’s younger brother Paolo, the lovers were discovered by her husband, who killed them, engulfed in a kiss, which caused them to be banished to Hell for eternity. When art critics first saw the sculpture in 1887, they suggested a more generic title, Le Baiser (The Kiss). Today, there are many reproductions, including one made of resin, offered by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $32.

Like a giant sculpture of wood and stone, the Woodruff barn sits proudly in front of a farm field, perhaps not as famous as Rodin’s work, but a thing of beauty, all the same.

Mrs. Rosalie Kuss, whose surname is a German word that means kiss, told us that the farm was originally settled by the Woodruff family. Unfortunately, a tornado in 1948 blew through the farm, destroying the old barns.

This one, a large barn with a gothic arch roof, a protruding second-story entrance to the haymow, and a striking fieldstone foundation, still functions. Besides providing plenty of room for straw and hay, it houses hogs, cattle, and sheep. These days, it’s owned by the Woodruff Family Trust. But the story goes to Rosalie and her last name, which she acquired when she remarried after her first husband died.

The Kiss is an iconic sculpture by Auguste Rodin, the famous French artist, who sculpted another classic, The Thinker, both of which are displayed in the Rodin museum in Paris. The Kiss, made of marble in 1882, depicts a couple, kissing in an embrace, a piece that appeared originally as part of a group of reliefs decorating Rodin’s monumental bronze portal, The Gates of Hell, commissioned for a planned museum of art in Paris. The sculpture was originally titled Francesca da Rimini, after the 13th-century Italian noblewoman immortalized in Dante’s Inferno. After Francesca fell in love with her husband’s younger brother Paolo, the lovers were discovered by her husband, who killed them, engulfed in a kiss, which caused them to be banished to Hell for eternity. When art critics first saw the sculpture in 1887, they suggested a more generic title, Le Baiser (The Kiss). Today, there are many reproductions, including one made of resin, offered by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $32.

Like a giant sculpture of wood and stone, the Woodruff barn sits proudly in front of a farm field, perhaps not as famous as Rodin’s work, but a thing of beauty, all the same.

“Nutwood”

Webster defines nutwood as any nutbearing tree or its wood. In 1815 when this farm’s history began, plenty of nutbearing trees dotted the Ohio landscape, such as chestnut, walnut, and hickory. Perhaps William Ward, the farm’s founder, named his farm, “Nutwood Place,” after such trees.

Ward, a native of Virginia, served as an officer in the Revolutionary War, and, both educated and business-saavy, he made the most of his and his father’s war service land grants. Moving to Maysville, Kentucky, he claimed land that had been axe marked by Simon Kenton, the legendary frontiersman, who, unfortunately basically illiterate, never bothered to register his claimed land. However, Ward and Kenton became business partners.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Webster defines nutwood as any nutbearing tree or its wood. In 1815 when this farm’s history began, plenty of nutbearing trees dotted the Ohio landscape, such as chestnut, walnut, and hickory. Perhaps William Ward, the farm’s founder, named his farm, “Nutwood Place,” after such trees.

Ward, a native of Virginia, served as an officer in the Revolutionary War, and, both educated and business-saavy, he made the most of his and his father’s war service land grants. Moving to Maysville, Kentucky, he claimed land that had been axe marked by Simon Kenton, the legendary frontiersman, who, unfortunately basically illiterate, never bothered to register his claimed land. However, Ward and Kenton became business partners.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Pride of Paris”

As we drove by this imposing barn, I asked barn scout Ken to stop. He knocked on the farmhouse door while I took some photos of this majestic bank barn, but, without an answer, we moved on, hoping to learn more about the barn eventually. The slate roof on the attractive farmhouse suggests the barn was built likewise in the 19th century.

I liked the orange louvers and the fading red paint and I decided to reposition the large rocks into a stone foundation next to the bank. The tree and the telephone pole, both absent a hundred or so years ago, had to go, too. Such a barn didn’t deserve to be hidden.

Located in St. Paris, this farm may have traced back to the Civil War era, though the size of the barn hints that it wasn’t the first on this farmstead. Several outbuildings nearby also suggest that this farmer was prosperous and might have, at least at one time, had a dairy operation.

The first white settlers arrived here in 1797, two years after the Treaty of Greenville had opened up the Northwest Territory. Later, in 1831, David Huffman founded this town, naming it New Paris, after the French capital, though, after he learned that another Ohio town already had claimed that name, he changed it to St. Paris. It was incorporated as a village in 1858. The owners have maintained the barn well: the metal roof’s intact, lightning rods are in place, and the paint’s holding up. With regular maintenance, it will continue its legacy as the pride of (St.) Paris.

As we drove by this imposing barn, I asked barn scout Ken to stop. He knocked on the farmhouse door while I took some photos of this majestic bank barn, but, without an answer, we moved on, hoping to learn more about the barn eventually. The slate roof on the attractive farmhouse suggests the barn was built likewise in the 19th century.

I liked the orange louvers and the fading red paint and I decided to reposition the large rocks into a stone foundation next to the bank. The tree and the telephone pole, both absent a hundred or so years ago, had to go, too. Such a barn didn’t deserve to be hidden.

Located in St. Paris, this farm may have traced back to the Civil War era, though the size of the barn hints that it wasn’t the first on this farmstead. Several outbuildings nearby also suggest that this farmer was prosperous and might have, at least at one time, had a dairy operation.

The first white settlers arrived here in 1797, two years after the Treaty of Greenville had opened up the Northwest Territory. Later, in 1831, David Huffman founded this town, naming it New Paris, after the French capital, though, after he learned that another Ohio town already had claimed that name, he changed it to St. Paris. It was incorporated as a village in 1858. The owners have maintained the barn well: the metal roof’s intact, lightning rods are in place, and the paint’s holding up. With regular maintenance, it will continue its legacy as the pride of (St.) Paris.

“A Genuine Gothic Gem”

When barn scout Ken and I passed by this barn, visible from Smith Road in St. Paris, I decided to stop for a long-distance look. The composition was a good one: a gothic arch-roofed barn (with another smaller one attached in the rear at a right angle), a tiny pond backed by a strand of pines, and a farm field in the foreground. It was an attractive scene.

Barns with such roofs are rarely seen today and they symbolize the end of the small barn in Ohio agriculture. Initially, barns had a simple gable roof, typical of barns in the United Kingdom and Europe for centuries. In the 1870s, a clever farmer or barn builder invented the gambrel roof, a two-planed surface, which was designed to enlarge storage space for the haymow. Then, although gothic arched roofs originated in the late 19th century in dairy-rich Michigan, they became more popular in the 1920s and their use peaked in the 1930s. These roofs had the same purpose as the gambrel variety – more storage space.

In 1916 an agricultural magazine, the Idaho Farmer, predicted that the gothic arch barn “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy barns,” which proved partly true in the 1920s. Farmers were practical people and, just as in the case of the round barn craze, they continued to build traditional rectangular-shaped barns with gable or gambrel roofs. Unlike the straight rafters in the gambrel roof, those in a gothic arch roof had to be curved, which was more expensive.

However, in the 1918 Sears catalog, The Book of Barns - Honor-Bilt-Already Cut, the most popular design was the gothic arch barn. The kit, complete with all pre-cut lumber and construction plans, sold for $1,500. Was this barn built, using the Sears kit? Maybe, maybe not.

Regardless, current owners have decided to save it – rather than replacing it with a modern pole barn, one large enough to house giant farm machinery. Hopefully their barn will continue to be maintained for many years. After all, it’s genuine Gothic.

When barn scout Ken and I passed by this barn, visible from Smith Road in St. Paris, I decided to stop for a long-distance look. The composition was a good one: a gothic arch-roofed barn (with another smaller one attached in the rear at a right angle), a tiny pond backed by a strand of pines, and a farm field in the foreground. It was an attractive scene.

Barns with such roofs are rarely seen today and they symbolize the end of the small barn in Ohio agriculture. Initially, barns had a simple gable roof, typical of barns in the United Kingdom and Europe for centuries. In the 1870s, a clever farmer or barn builder invented the gambrel roof, a two-planed surface, which was designed to enlarge storage space for the haymow. Then, although gothic arched roofs originated in the late 19th century in dairy-rich Michigan, they became more popular in the 1920s and their use peaked in the 1930s. These roofs had the same purpose as the gambrel variety – more storage space.

In 1916 an agricultural magazine, the Idaho Farmer, predicted that the gothic arch barn “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy barns,” which proved partly true in the 1920s. Farmers were practical people and, just as in the case of the round barn craze, they continued to build traditional rectangular-shaped barns with gable or gambrel roofs. Unlike the straight rafters in the gambrel roof, those in a gothic arch roof had to be curved, which was more expensive.

However, in the 1918 Sears catalog, The Book of Barns - Honor-Bilt-Already Cut, the most popular design was the gothic arch barn. The kit, complete with all pre-cut lumber and construction plans, sold for $1,500. Was this barn built, using the Sears kit? Maybe, maybe not.

Regardless, current owners have decided to save it – rather than replacing it with a modern pole barn, one large enough to house giant farm machinery. Hopefully their barn will continue to be maintained for many years. After all, it’s genuine Gothic.

“The Seed House”

I first noticed this unusual barn on my early morning drive from Sidney to Urbana, where I met barn scout Ken Wright, who agreed that we could include it on our tour. Driving back along Route 29, just past Wesley Chapel Road, we pulled into a driveway – on the opposite side of the road from the barn. Luckily, a fellow in a tractor slowed down to chat with us.

Rodney McGill called this barn a “seed house” and said that his brother Roger owns it. He thought that it was built in the 1930s, challenging years for most farmers during the Great Depression. Many, mortgaged to the hilt, lost their barns to banks. Few built new ones. Perhaps these hard times were why the barn is such a small one.

Well, small it may be, but it’s brick, has a gambrel roof, and decorative lightning rods, all clues that this farmer knew what he was doing and had enough money to afford to build this sturdy barn. The add-on in the rear came later: a hodgepodge of glazed tile, a brick that differs from the main barn, and wooden siding, which has seen better days. The chimney likely was added more recently, a rarity, due to the hazard of fire, though sometimes it’s seen in Ohio’s tobacco barns. The three metal corn cribs seem to be in excellent condition.

The owner has covered one wall with horizontal aluminum siding and has installed an electric garage door, hinting that this barn is still being used, though probably not for storing agricultural products. A seed house no longer, it still stands as it approaches the century mark, reminding us of the wise farmer, who built it during the dark days of the Great Depression.

I first noticed this unusual barn on my early morning drive from Sidney to Urbana, where I met barn scout Ken Wright, who agreed that we could include it on our tour. Driving back along Route 29, just past Wesley Chapel Road, we pulled into a driveway – on the opposite side of the road from the barn. Luckily, a fellow in a tractor slowed down to chat with us.

Rodney McGill called this barn a “seed house” and said that his brother Roger owns it. He thought that it was built in the 1930s, challenging years for most farmers during the Great Depression. Many, mortgaged to the hilt, lost their barns to banks. Few built new ones. Perhaps these hard times were why the barn is such a small one.

Well, small it may be, but it’s brick, has a gambrel roof, and decorative lightning rods, all clues that this farmer knew what he was doing and had enough money to afford to build this sturdy barn. The add-on in the rear came later: a hodgepodge of glazed tile, a brick that differs from the main barn, and wooden siding, which has seen better days. The chimney likely was added more recently, a rarity, due to the hazard of fire, though sometimes it’s seen in Ohio’s tobacco barns. The three metal corn cribs seem to be in excellent condition.

The owner has covered one wall with horizontal aluminum siding and has installed an electric garage door, hinting that this barn is still being used, though probably not for storing agricultural products. A seed house no longer, it still stands as it approaches the century mark, reminding us of the wise farmer, who built it during the dark days of the Great Depression.

“Mad River Barn”

As we drove by this handsome barn with a green roof and brooding cement silo, I asked barn scout Ken to stop. Like the gothic roofed barn, it offered a good composition: a farm field leading to the barn, a small white farmhouse nearby, and a hillside full of trees in the background. Although the April foilage was less than glamorous, I tried to imagine it with the colors of autumn.

Ken told me that the farm is close to the Mad River, a name that has always intrigued me, though I knew little about it. Named initially by the Shawnees for its rapid, angry current, this 66-mile-long river empties into the Great Miami near Dayton. Its source lies in Logan County on a plateau on Campbell Hill, which, though inside Bellefontaine’s city limits, is the highest point in Ohio at 1,549 feet. This ranks the state in 43rd place in highest point in elevation in the U.S, which means that we Ohioans live in a pretty flat place.

In 1795, the same year as the Treaty of Greenville, the Mad River Road was cut to encourage settlement into this flat, fertile land. Cities like Dayton (1796), Springfield (1801), Urbana (1805), Sidney (1819), and Bellefontaine (1820) became county seats as the western part of the Ohio Country became established.

Today, the Mad River is Ohio’s largest cold water fishery, being stocked annually with rainbow and brown trout. And there’s no doubt that the Native Americans and the early settlers of this area, perhaps even on this 19th-century farmstead, fished in the Mad River. Though we saw the barn only from a distance on Route 29, it appeared to be in good condition and, assuming the owner farms this field, is probably still being used, though the owners no longer catch their dinners in the river.

As we drove by this handsome barn with a green roof and brooding cement silo, I asked barn scout Ken to stop. Like the gothic roofed barn, it offered a good composition: a farm field leading to the barn, a small white farmhouse nearby, and a hillside full of trees in the background. Although the April foilage was less than glamorous, I tried to imagine it with the colors of autumn.

Ken told me that the farm is close to the Mad River, a name that has always intrigued me, though I knew little about it. Named initially by the Shawnees for its rapid, angry current, this 66-mile-long river empties into the Great Miami near Dayton. Its source lies in Logan County on a plateau on Campbell Hill, which, though inside Bellefontaine’s city limits, is the highest point in Ohio at 1,549 feet. This ranks the state in 43rd place in highest point in elevation in the U.S, which means that we Ohioans live in a pretty flat place.

In 1795, the same year as the Treaty of Greenville, the Mad River Road was cut to encourage settlement into this flat, fertile land. Cities like Dayton (1796), Springfield (1801), Urbana (1805), Sidney (1819), and Bellefontaine (1820) became county seats as the western part of the Ohio Country became established.

Today, the Mad River is Ohio’s largest cold water fishery, being stocked annually with rainbow and brown trout. And there’s no doubt that the Native Americans and the early settlers of this area, perhaps even on this 19th-century farmstead, fished in the Mad River. Though we saw the barn only from a distance on Route 29, it appeared to be in good condition and, assuming the owner farms this field, is probably still being used, though the owners no longer catch their dinners in the river.

“A Family Affair”

Early one April morning I drove by this barn after leaving Shelby County – where I did a fundraiser event in 2022 – and noticed a decorated barn roof, featuring a large “M.” Intrigued and thinking the roof might have been slate, I resolved to return when barn scout Ken and I would do our barn tour a little later in the day.

Upon our return, Ken noticed a phone number and called, talking with Melanie Moore, who owns the barn with her husband Doug. She told Ken that she’d give permission for us to look around and for me to include the barn in my Ohio Barn Project. After getting the composition – a nice one with a string of wooden fence posts leading back to the barn – we left. Later, I made contact with Doug, who forwarded information. He said that the farmstead, originally over 80 acres, has been in the family for four generations. The oldest deed is dated 1903, though the farm was likely founded well before then.

Clarence Ray and Lola Faye Moore were the first of this family to own the farm. Eventually – after surviving the collapse of farm prices in the 1920s and the terrible Great Depression – the farm passed to Doug and Melanie, who purchased it in the early 1990s. Their son Shem helps Doug run the farm and oldest son Landon and his wife Nicole live next door on seven acres, which used to be part of the farmstead.

Memories from earlier days include Doug’s dad Charles and aunt Maxine Neese being born in the farmhouse in the early 1920s and Charles and his mother Faye milking their six Jersey cows in the 1930s and 1940s. They would make enough butter to trade for sugar and flour at the nearby Rosewood grocery store. Today Doug and son Shem feed the horses and cattle and milk the goats, continuing to make more Moore memories on this farmstead, truly a family affair.

Early one April morning I drove by this barn after leaving Shelby County – where I did a fundraiser event in 2022 – and noticed a decorated barn roof, featuring a large “M.” Intrigued and thinking the roof might have been slate, I resolved to return when barn scout Ken and I would do our barn tour a little later in the day.

Upon our return, Ken noticed a phone number and called, talking with Melanie Moore, who owns the barn with her husband Doug. She told Ken that she’d give permission for us to look around and for me to include the barn in my Ohio Barn Project. After getting the composition – a nice one with a string of wooden fence posts leading back to the barn – we left. Later, I made contact with Doug, who forwarded information. He said that the farmstead, originally over 80 acres, has been in the family for four generations. The oldest deed is dated 1903, though the farm was likely founded well before then.

Clarence Ray and Lola Faye Moore were the first of this family to own the farm. Eventually – after surviving the collapse of farm prices in the 1920s and the terrible Great Depression – the farm passed to Doug and Melanie, who purchased it in the early 1990s. Their son Shem helps Doug run the farm and oldest son Landon and his wife Nicole live next door on seven acres, which used to be part of the farmstead.

Memories from earlier days include Doug’s dad Charles and aunt Maxine Neese being born in the farmhouse in the early 1920s and Charles and his mother Faye milking their six Jersey cows in the 1930s and 1940s. They would make enough butter to trade for sugar and flour at the nearby Rosewood grocery store. Today Doug and son Shem feed the horses and cattle and milk the goats, continuing to make more Moore memories on this farmstead, truly a family affair.

“Mast’s Marvel”

As we began our barn tour in April, 2022, Ken and I both noticed a striking German forebay barn, visible clearly from the road, and decided to take a look. By chance, Tim Schwaderer, who owns the farm with his wife Debbie, was outside and willing to let me include his barn in my old barn preservation project.

Although only three acres, the farm’s two buildings, both gems in their own right, more than compensate for the small size. The magnificent three-floor brick farmhouse, the rear section originally built in 1840, sports an impressive Victorian front, added in 1878. Tim and his wife have remodeled it, preserving its historical features, and plan to offer it in a county-wide home tour.

John Mast, the founder, also built this large barn in 1840, one of the earliest in this county, which was created at the urgings of Revolutionary War veteran William Ward, who also lobbied to have Urbana be named the county seat. After purchasing it, Absalom Jennings named Ward’s farm, “Nutwood Place,” and then built his famous brick round barn there in 1858.