ILLINOIS

CHAMPAIGN COUNTY

“The Experiment”

Ironically, the University of Illinois authorities ordered these three round barns to be constructed well after New York’s Eliot Stewart, who promoted his octagonal barn design in the mid-1870s, admitted in 1892 that round barns were more difficult – and therefore more expensive – to build than their rectangular counterparts. This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Ironically, the University of Illinois authorities ordered these three round barns to be constructed well after New York’s Eliot Stewart, who promoted his octagonal barn design in the mid-1870s, admitted in 1892 that round barns were more difficult – and therefore more expensive – to build than their rectangular counterparts. This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

KANE COUNTY

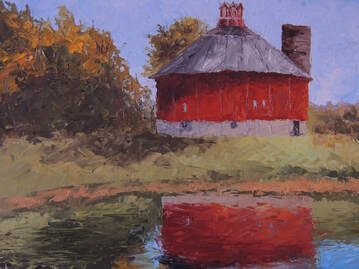

“Teeple’s Thorn”

One of the selling points – circa 1890s – of round barns was their self-supporting roof, which proponents claimed was more wind resistant than that of conventional designs. This concept must have appealed to Lester Teeple, who built this 16-sided barn in 1885, about ten years after New York’s Elliot Stewart wrote about his octagonal barn in widely-read agricultural journals.

In fact, although Teeple wanted the octagonal shape – also the favorite shape of Thomas Jefferson – the lumber he chose was not long enough to build this polygon, which is puzzling since he owned a lumber yard. Instead, he hired Elgin-based architect W. Wright Abell to design the barn in 16 sections, technically a hexadecagon. George Washington built one in 1793 and Ohio’s only 16-sided barn still stands, “Workley’s Wonder,” deep in the woodlands of Harrison County.

Teeple built the barn in 1885 – with a diameter of 85 feet and a height of 85 feet – classic architectural barn alliteration. A dairy farmer, he intended the barn for his herd of – not 85 – but 65 Red Poll cattle, a breed that was known for good for both beef and milk production. In 1952 the owners installed concrete buttresses to allow modern farm machines to be stored on the brick floor, which sat on top of a fieldstone foundation. The barn was busy in those years – housing hay, straw, grain, and the herd of dairy cows.

Unfortunately, high winds often blow in that area, occasionally kicking up a tornado, one of which took off the attractive red and white cupola in 1973. Additionally, progress in the growth and development around Chicago (Elgin is only 35 miles away) meant that many old barns and farms were becoming industrial property. Randall Road, where the barn sat, became an exit off I-90, giving passing motorists a glimpse of the barn as they whizzed by it. Deservedly, it merited inclusion into the National Register in 1979 and its proximity to Chicago helped publicize its uniqueness. It had remained in the Teeple family for over a century.

However the barn began to deteriorate during the 1980s and the family eventually sold it. Concerned preservationists formed a nonprofit group, AgTech, in 1996 and three years later they restored the striking cupola, a restoration that cost $100,000. More attention came when the National Geographic included the barn in its 2001 book, Saving America’s Treasures, which evolved from a public-private partnership between the National Parks Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Three years later, Ag Tech, an offshoot of the Kane County Farm Bureau, was scheduling fundraisers to restore the barn, which was estimated to need $3 million for structural repairs and for a conversion into a resource center for agricultural science. By October it had raised $50,000 towards a matching grant of $149,000. With sadness, their efforts were too little and too late.

In May, 2007, strong prairie winds ripped off the roof, making the barn a total loss. The owner, a nut-processing company tried to preserve the cupola and whatever else was salvageable.

But its memory lives on, not only in this painting and essay but in a scale model, built by Dick and Joann Lichthardt, who toured the barn before it collapsed. They wanted to add it to their village of miniatures, including a schoolhouse, church, buggy shed, hog barn and chicken shed. It took these two history lovers 18 months to finish the model, which is on a scale of a half inch per foot and includes dairy cattle, farm workers, a dog, hay stacks, and a hay fork. After the artisans completed their model, they displayed it for the first time at the Illinois Steam Power Show in 2005. Today it stands proudly in the lobby at Kane County Farm Bureau, where it will remain as a reminder of what once was before high winds became the thorn in Teeple’s side.

One of the selling points – circa 1890s – of round barns was their self-supporting roof, which proponents claimed was more wind resistant than that of conventional designs. This concept must have appealed to Lester Teeple, who built this 16-sided barn in 1885, about ten years after New York’s Elliot Stewart wrote about his octagonal barn in widely-read agricultural journals.

In fact, although Teeple wanted the octagonal shape – also the favorite shape of Thomas Jefferson – the lumber he chose was not long enough to build this polygon, which is puzzling since he owned a lumber yard. Instead, he hired Elgin-based architect W. Wright Abell to design the barn in 16 sections, technically a hexadecagon. George Washington built one in 1793 and Ohio’s only 16-sided barn still stands, “Workley’s Wonder,” deep in the woodlands of Harrison County.

Teeple built the barn in 1885 – with a diameter of 85 feet and a height of 85 feet – classic architectural barn alliteration. A dairy farmer, he intended the barn for his herd of – not 85 – but 65 Red Poll cattle, a breed that was known for good for both beef and milk production. In 1952 the owners installed concrete buttresses to allow modern farm machines to be stored on the brick floor, which sat on top of a fieldstone foundation. The barn was busy in those years – housing hay, straw, grain, and the herd of dairy cows.

Unfortunately, high winds often blow in that area, occasionally kicking up a tornado, one of which took off the attractive red and white cupola in 1973. Additionally, progress in the growth and development around Chicago (Elgin is only 35 miles away) meant that many old barns and farms were becoming industrial property. Randall Road, where the barn sat, became an exit off I-90, giving passing motorists a glimpse of the barn as they whizzed by it. Deservedly, it merited inclusion into the National Register in 1979 and its proximity to Chicago helped publicize its uniqueness. It had remained in the Teeple family for over a century.

However the barn began to deteriorate during the 1980s and the family eventually sold it. Concerned preservationists formed a nonprofit group, AgTech, in 1996 and three years later they restored the striking cupola, a restoration that cost $100,000. More attention came when the National Geographic included the barn in its 2001 book, Saving America’s Treasures, which evolved from a public-private partnership between the National Parks Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Three years later, Ag Tech, an offshoot of the Kane County Farm Bureau, was scheduling fundraisers to restore the barn, which was estimated to need $3 million for structural repairs and for a conversion into a resource center for agricultural science. By October it had raised $50,000 towards a matching grant of $149,000. With sadness, their efforts were too little and too late.

In May, 2007, strong prairie winds ripped off the roof, making the barn a total loss. The owner, a nut-processing company tried to preserve the cupola and whatever else was salvageable.

But its memory lives on, not only in this painting and essay but in a scale model, built by Dick and Joann Lichthardt, who toured the barn before it collapsed. They wanted to add it to their village of miniatures, including a schoolhouse, church, buggy shed, hog barn and chicken shed. It took these two history lovers 18 months to finish the model, which is on a scale of a half inch per foot and includes dairy cattle, farm workers, a dog, hay stacks, and a hay fork. After the artisans completed their model, they displayed it for the first time at the Illinois Steam Power Show in 2005. Today it stands proudly in the lobby at Kane County Farm Bureau, where it will remain as a reminder of what once was before high winds became the thorn in Teeple’s side.

OGLE COUNTY

“The Oval”

In 1901, seven years before the University of Illinois began its experimental agricultural station and its three round barns, Jeremiah Shaffer and his five brothers-in-law, the Haases, began building round barns in Ogle and Stephenson counties in the northwestern corner of Illinois, bordering dairy-rich Wisconsin. Though Shaffer, born in Stephenson County, was a school teacher, he read voraciously, which is how he presumably acquired knowledge about round barns and Professor King’s 1890 round dairy barn. He and his team built many of them in Stephenson County, which, in the 1984 group submission to the National Register of Historic Places, still had 21 round barns, more than any other county in America. As of 2007, five of these, on the register, still survive. Most were built by Shaffer and the Haas brothers. CLICK HERE FOR THE STORY

In 1901, seven years before the University of Illinois began its experimental agricultural station and its three round barns, Jeremiah Shaffer and his five brothers-in-law, the Haases, began building round barns in Ogle and Stephenson counties in the northwestern corner of Illinois, bordering dairy-rich Wisconsin. Though Shaffer, born in Stephenson County, was a school teacher, he read voraciously, which is how he presumably acquired knowledge about round barns and Professor King’s 1890 round dairy barn. He and his team built many of them in Stephenson County, which, in the 1984 group submission to the National Register of Historic Places, still had 21 round barns, more than any other county in America. As of 2007, five of these, on the register, still survive. Most were built by Shaffer and the Haas brothers. CLICK HERE FOR THE STORY

“The Donut”

Appearing, from a distance, similar to the oval-shaped barn, the “donut” differs in that, especially from an aerial view, it resembles an actual donut – with a hole in the middle. Was this done to provide light into the inner parts of the barn? For time savings in feeding livestock? Or just to be different? Whatever the reason, the design didn’t catch on in other counties. Outside of Ogle and adjacent Stephenson counties, there are no existing round barns of this type. Of course, that doesn’t infer that such barns weren’t built elsewhere but it’s unlikely that they were. Of the seven such barns in these two counties, this one was the oldest, dating to 1898.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.

Appearing, from a distance, similar to the oval-shaped barn, the “donut” differs in that, especially from an aerial view, it resembles an actual donut – with a hole in the middle. Was this done to provide light into the inner parts of the barn? For time savings in feeding livestock? Or just to be different? Whatever the reason, the design didn’t catch on in other counties. Outside of Ogle and adjacent Stephenson counties, there are no existing round barns of this type. Of course, that doesn’t infer that such barns weren’t built elsewhere but it’s unlikely that they were. Of the seven such barns in these two counties, this one was the oldest, dating to 1898.

This fascinating essay will be posted eventually.