Barns Outside of Ohio

As I travel to other parts of the country, I sometimes find a barn or an old building I admire and paint it. If it has some history behind it, I write about it. The Whitley County, Indiana, paintings have been offered in fundraisers in July during the county fair in Columbia City.

FLORIDA

Alachua County

“Marjorie”

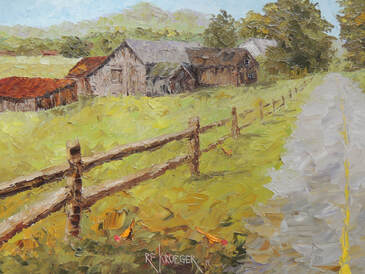

In the 18th and 19th centuries Florida and most of the southern states were not blessed with hardwood forests, temperate growing seasons, and an influx of European barn builders as were Ohio and its Midwestern neighbors. As a result, there aren’t many old barns lurking about in the sunshine state. Finally I decided to visit the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings state park, located about 90 minutes from St. Augustine in tiny Cross Creek, so named because it lies between two lakes. Her old barn drew me here.

Mrs. Rawlings, thanks to an inheritance from her mother, moved here in 1928 with her husband Charles and purchased a 72-acre orange grove. A former newspaper reporter, she continued writing, short stories at first, and later novels – about her neighbors, Florida cracker people, rural descendants of the British and American pioneers who settled in Florida after Spain ceded it to Britain in 1763. Her first novel, South Moon Under, was published in 1933, the same year her husband divorced her. He didn’t like living in rural Florida. No air conditioning in those years. However, Marjorie continued writing and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1939 for her novel The Yearling. Seven years later a movie followed, making her famous. Ignoring this fame, she continued to live on her farm in Cross Creek and farm, writing more stories and a few novels.

The farm was established in the late 1800s and the farmhouse dates to 1884, but the barn has been reconstructed. Though mainly an orange grove, the farm may have raised other citrus crops and vegetables, which Marjorie delighted in cooking, “I get as much satisfaction from preparing a perfect dinner for a few good friends as from turning out a perfect paragraph in my writing.” Though she also loved the remoteness of Cross Creek, she eventually moved – with her second husband – to Crescent Beach, just south of St. Augustine, where she wintered while spending summers in New York state.

There wasn’t much to this barn, which, though its siding had weathered into grays and browns, served to house the crops of oranges, a cow, and a mule. Life here during the Great Depression must have been a frugal existence, but one that inspired Marjorie to write … and write well enough to win the Pulitzer. I’d like to think that the barn played some role in that.

“Marjorie”

In the 18th and 19th centuries Florida and most of the southern states were not blessed with hardwood forests, temperate growing seasons, and an influx of European barn builders as were Ohio and its Midwestern neighbors. As a result, there aren’t many old barns lurking about in the sunshine state. Finally I decided to visit the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings state park, located about 90 minutes from St. Augustine in tiny Cross Creek, so named because it lies between two lakes. Her old barn drew me here.

Mrs. Rawlings, thanks to an inheritance from her mother, moved here in 1928 with her husband Charles and purchased a 72-acre orange grove. A former newspaper reporter, she continued writing, short stories at first, and later novels – about her neighbors, Florida cracker people, rural descendants of the British and American pioneers who settled in Florida after Spain ceded it to Britain in 1763. Her first novel, South Moon Under, was published in 1933, the same year her husband divorced her. He didn’t like living in rural Florida. No air conditioning in those years. However, Marjorie continued writing and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1939 for her novel The Yearling. Seven years later a movie followed, making her famous. Ignoring this fame, she continued to live on her farm in Cross Creek and farm, writing more stories and a few novels.

The farm was established in the late 1800s and the farmhouse dates to 1884, but the barn has been reconstructed. Though mainly an orange grove, the farm may have raised other citrus crops and vegetables, which Marjorie delighted in cooking, “I get as much satisfaction from preparing a perfect dinner for a few good friends as from turning out a perfect paragraph in my writing.” Though she also loved the remoteness of Cross Creek, she eventually moved – with her second husband – to Crescent Beach, just south of St. Augustine, where she wintered while spending summers in New York state.

There wasn’t much to this barn, which, though its siding had weathered into grays and browns, served to house the crops of oranges, a cow, and a mule. Life here during the Great Depression must have been a frugal existence, but one that inspired Marjorie to write … and write well enough to win the Pulitzer. I’d like to think that the barn played some role in that.

GEORGIA

FULTON COUNTY

"Broken"

I title it "Broken" since many parts of it are indeed broken - collapsing roof, missing boards. In fact, it may be gone by now. A friend found the composition and asked me to paint it for a fundraiser for her daughter's Atlanta suburban school, which educates special needs children.

I think that there's a good parallel between this deteriorated barn and the human condition. So I included a quote, which came from my heart.

"I like broken sea shells. They remind me of our lives and hearts, which sometimes get broken. What's important is what we do with the pieces."

"Broken"

I title it "Broken" since many parts of it are indeed broken - collapsing roof, missing boards. In fact, it may be gone by now. A friend found the composition and asked me to paint it for a fundraiser for her daughter's Atlanta suburban school, which educates special needs children.

I think that there's a good parallel between this deteriorated barn and the human condition. So I included a quote, which came from my heart.

"I like broken sea shells. They remind me of our lives and hearts, which sometimes get broken. What's important is what we do with the pieces."

IDAHO

“Sho-Ban”

Discovering this barn in Idaho came purely by accident. I stumbled upon it in early September, 2016, while showing my son Jon around the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. We had come to Pocatello to run the annual marathon, which I had run ten years ago with a friend. My trip out West focused on spending time with my son and his young family, who moved to Salt Lake City six months ago.

Jon and I were looking for the tribal gift shop where I hoped I’d find a present for his wo-year-old son Colin. But we couldn’t find it. Instead, we drove by this old wooden barn, a charming one with a decorative shingled cupola perched on top. “This one has to be painted,” I told Jon. So he stopped the car and parked on the roadside berm. He stayed there while I walked down the gravel driveway, hoping for a pleasant welcome. Luckily I got one.

After I knocked on the door of a small house, I heard a voice inviting me inside. Kelly Wright, a tall hulk of a man, the program manager for environmental waste on the reservation, made me feel welcome. He offered to show me the barn and give me some wood for framing my painting. I promised to send a small study painting, along with this essay. Click here for the rest of this story - the tale of the Shoshone and Bannock tribes and their most famous member, Sacajawea, the guide of Lewis and Clark.

Discovering this barn in Idaho came purely by accident. I stumbled upon it in early September, 2016, while showing my son Jon around the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. We had come to Pocatello to run the annual marathon, which I had run ten years ago with a friend. My trip out West focused on spending time with my son and his young family, who moved to Salt Lake City six months ago.

Jon and I were looking for the tribal gift shop where I hoped I’d find a present for his wo-year-old son Colin. But we couldn’t find it. Instead, we drove by this old wooden barn, a charming one with a decorative shingled cupola perched on top. “This one has to be painted,” I told Jon. So he stopped the car and parked on the roadside berm. He stayed there while I walked down the gravel driveway, hoping for a pleasant welcome. Luckily I got one.

After I knocked on the door of a small house, I heard a voice inviting me inside. Kelly Wright, a tall hulk of a man, the program manager for environmental waste on the reservation, made me feel welcome. He offered to show me the barn and give me some wood for framing my painting. I promised to send a small study painting, along with this essay. Click here for the rest of this story - the tale of the Shoshone and Bannock tribes and their most famous member, Sacajawea, the guide of Lewis and Clark.

“St. Anthony”

What brought me to Idaho in August of 2018 was not barn painting but rather the Mesa Falls marathon, which I felt owed me – after a disappointing injury-plagued performance in it the previous year. And, since I had plenty of time, I decided to hunt for barns. I found several.

One of them was in the city limits of St. Anthony, a town not founded until the 1890s, despite a nearby wooden fort built in 1811 by Major Andrew Henry, who was following on the footsteps of Lewis and Clark. Today the town’s population is under 4,000, a number exceeded by the 2.500 elk that winter here, along with 500 moose and 1,500 mule deer. Most of the animals stay in the 10,000 acres of a natural quartz sand dune region, which I visited – before I ran the marathon.

I did paintings of other barns as well – in nearby Ashton – but this one was the most intriguing. Unlike most of the others, this one was still in good shape. I wondered why so many western barns are deteriorating and speculated that the early barn builders either didn’t know their craft or didn’t have access to the hardwood timber so plentiful in early Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky – where barns much older than these still flourish.

What brought me to Idaho in August of 2018 was not barn painting but rather the Mesa Falls marathon, which I felt owed me – after a disappointing injury-plagued performance in it the previous year. And, since I had plenty of time, I decided to hunt for barns. I found several.

One of them was in the city limits of St. Anthony, a town not founded until the 1890s, despite a nearby wooden fort built in 1811 by Major Andrew Henry, who was following on the footsteps of Lewis and Clark. Today the town’s population is under 4,000, a number exceeded by the 2.500 elk that winter here, along with 500 moose and 1,500 mule deer. Most of the animals stay in the 10,000 acres of a natural quartz sand dune region, which I visited – before I ran the marathon.

I did paintings of other barns as well – in nearby Ashton – but this one was the most intriguing. Unlike most of the others, this one was still in good shape. I wondered why so many western barns are deteriorating and speculated that the early barn builders either didn’t know their craft or didn’t have access to the hardwood timber so plentiful in early Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky – where barns much older than these still flourish.

INDIANA

Whitley County

“Nature’s Mousetraps”

This Pennsylvania German bank barn was one of the first that barn scout Ron took me to see on our tour in early December, 2023. Owners Carlene and her sister Darlene Schrider – the sixth generation of ownership – were kind enough to allow us to explore the barn. She explained there her great-great-grandfather Charles Frederick Hess emigrated from Baden, Germany, and purchased the land acquired in treaty with the Miami Indians in 1846.

As I walked around it, looking at the traditional forebay, I glanced upwards and noticed a hex-shaped hole near the top on the short end of the barn. I’m not sure if I had seen one of these on my many travels. Maybe I had, but it must not have registered. This was an owl hole, an opening that doubled as ventilation and as a way to rid the barn of vermin.

The tradition started in Great Britain and Germany at the end of the 17th century, when these holes were usually positioned on the gable end of the barn and under the eave. In stone barns – as were mostly built in Great Britain at that time, due to the shortage of wood that had been used for the Royal Navy – the owl hole often had a stone perch or landing platform, making it easier for the bird to enter the oblong hole, usually six to nine inches. This size was large enough for a barn owl and small enough to keep out larger predators. The holes also provided ventilation and illumination, though their principal purpose was rodent control. (The rest of the essay upon request.)

This Pennsylvania German bank barn was one of the first that barn scout Ron took me to see on our tour in early December, 2023. Owners Carlene and her sister Darlene Schrider – the sixth generation of ownership – were kind enough to allow us to explore the barn. She explained there her great-great-grandfather Charles Frederick Hess emigrated from Baden, Germany, and purchased the land acquired in treaty with the Miami Indians in 1846.

As I walked around it, looking at the traditional forebay, I glanced upwards and noticed a hex-shaped hole near the top on the short end of the barn. I’m not sure if I had seen one of these on my many travels. Maybe I had, but it must not have registered. This was an owl hole, an opening that doubled as ventilation and as a way to rid the barn of vermin.

The tradition started in Great Britain and Germany at the end of the 17th century, when these holes were usually positioned on the gable end of the barn and under the eave. In stone barns – as were mostly built in Great Britain at that time, due to the shortage of wood that had been used for the Royal Navy – the owl hole often had a stone perch or landing platform, making it easier for the bird to enter the oblong hole, usually six to nine inches. This size was large enough for a barn owl and small enough to keep out larger predators. The holes also provided ventilation and illumination, though their principal purpose was rodent control. (The rest of the essay upon request.)

“The Fahl Family”

Barn scout Ron explained that Greg Fahl owns this large white barn, impressive both in size and in condition. I wanted to include the red trim around the windows and the family name above the entrance, but the composition had to feature the recently harvested fields that sweep upwards towards woodlands in the distance. Unfortunately, Greg couldn’t be there when we visited – to explain the history of this barn and its adjacent silo. But with the excellent maintenance it has received, it should remain in the family for many years to come.

Barn scout Ron explained that Greg Fahl owns this large white barn, impressive both in size and in condition. I wanted to include the red trim around the windows and the family name above the entrance, but the composition had to feature the recently harvested fields that sweep upwards towards woodlands in the distance. Unfortunately, Greg couldn’t be there when we visited – to explain the history of this barn and its adjacent silo. But with the excellent maintenance it has received, it should remain in the family for many years to come.

“660W”

As barn scout Ron drove by this old barn on Road 600W, I asked him to stop. Apparently, the barn’s basically abandoned and on its last legs. Yet, there was something about it that appealed to me – almost as if it were screaming, “Don’t forget that I was once a great barn.” So, we stopped.

Its large haymow and pronounced pointed hayhood hinted that hay storage was a principal function of this old barn. And, it justified the farmer installing a metal roof, still in pretty good shape. However, weeds and scrub are beginning to take over, its missing siding allows water to penetrate, and there are no farm fields in sight. So, yes, this barn’s glory days long gone and it may be remembered only in this painting, a faded memory on 600W.

As barn scout Ron drove by this old barn on Road 600W, I asked him to stop. Apparently, the barn’s basically abandoned and on its last legs. Yet, there was something about it that appealed to me – almost as if it were screaming, “Don’t forget that I was once a great barn.” So, we stopped.

Its large haymow and pronounced pointed hayhood hinted that hay storage was a principal function of this old barn. And, it justified the farmer installing a metal roof, still in pretty good shape. However, weeds and scrub are beginning to take over, its missing siding allows water to penetrate, and there are no farm fields in sight. So, yes, this barn’s glory days long gone and it may be remembered only in this painting, a faded memory on 600W.

“St. Rt. 205”

As we passed this little bank barn, Ron and I decided that it was worth a stop. After an unsuccessful knock on the farmhouse door, we looked around. Apparently, this little barn is in use: its metal roof is in good repair and the siding is intact, though a little weathered. Distant fields behind the barn show that this, indeed, is farm country and that perhaps some of the harvest is stored in the barn. Though the barn doors had a fresh coat of white paint, I decided to give them the weathered gray look of the rest of the barn.

As we passed this little bank barn, Ron and I decided that it was worth a stop. After an unsuccessful knock on the farmhouse door, we looked around. Apparently, this little barn is in use: its metal roof is in good repair and the siding is intact, though a little weathered. Distant fields behind the barn show that this, indeed, is farm country and that perhaps some of the harvest is stored in the barn. Though the barn doors had a fresh coat of white paint, I decided to give them the weathered gray look of the rest of the barn.

“The Sentinel”

It sits there quietly like a lonely sentinel, looking over acres of farmland, wooded forest in the distance. Built into a natural bank, the barn goes back a long way, as its rugged hand-hewn timbers attest – probably to somewhere between 1840 and 1870. Christian Doenges, Sr., bought the farm and the barn in 1905 and passed it on to his children where it has remained for over a century. And, constructed well, it survives, its siding and roof intact, along with an impressive new course of stonework, recently completed in 2017 by the owner, Virginia Doenges.

Though on a tour a few years ago we didn’t have the chance to meet her on our tour, barn scout Ron Myer and I met Virginia on this trip in December, 2023. She was happy that I’d be doing another painting of her historic barn. A great friend of the agricultural museum’s trustees, Virginia allows them to use her barn for storage of new additions – antiques and memorabilia that they acquire. And the barn, if it could talk, would affirm that it’s glad to be of use again.

It sits there quietly like a lonely sentinel, looking over acres of farmland, wooded forest in the distance. Built into a natural bank, the barn goes back a long way, as its rugged hand-hewn timbers attest – probably to somewhere between 1840 and 1870. Christian Doenges, Sr., bought the farm and the barn in 1905 and passed it on to his children where it has remained for over a century. And, constructed well, it survives, its siding and roof intact, along with an impressive new course of stonework, recently completed in 2017 by the owner, Virginia Doenges.

Though on a tour a few years ago we didn’t have the chance to meet her on our tour, barn scout Ron Myer and I met Virginia on this trip in December, 2023. She was happy that I’d be doing another painting of her historic barn. A great friend of the agricultural museum’s trustees, Virginia allows them to use her barn for storage of new additions – antiques and memorabilia that they acquire. And the barn, if it could talk, would affirm that it’s glad to be of use again.

“Churubusco”

When barn scout Ron drove by this weathered barn in November, 2020, I asked him to stop, even though he didn’t know the owners. The barn had been neglected, its roof showing several holes, allowing dangerous watery penetration, although its weather vanes still protected against a lightning strike.

The barn sat near an intersection in Churusbusco, often referred to by locals as simply, “Busco.” The village lies near the headwaters of the Eel River in the extreme northeast corner of Whitley County, about 15 miles from Ft. Wayne, and represents Americana at its best: a population of under 2,000, a large town clock, two traffic lights, free parking along the storefronts, and a Citgo gas station.

Churubusco, named in honor of the 1847 Battle of Churubusco, which was fought in Mexico during the Mexican–American War, originally comprised two towns. Both were founded in the 19th century by European Americans – Union and Franklin, named after one of our founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin. They bordered each other across a railroad track. Prior to the 1840s, residents of the two towns had to travel 11 miles – by foot or horse and buggy – to Columbia City to get their mail. Eventually the towns grew enough to qualify for their own post office but, since they were in the same location, the government ordered them to apply for a joint post office. They couldn’t use their names since both were used elsewhere in the state.

At a joint community meeting, local school teacher Eliza Rich suggested merging the two towns and adopting the name, Churubusco, since the battle, only a year earlier, resulted in a decisive American victory, instilling as much patriotism as the names, Union and Franklin. The Churubusco post office has been in operation since 1848. The Spanish name refers to temple that commemorates the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli. The area is bordered by the river, Churusbusco, in Mexico City.

I liked the barn, whose red paint has faded to gray and whose green shingled roof has seen better days. However, at one time, the farmer must have been doing well since the adjacent milk house has a matching green roof. Inside, the post and beam construction is primarily saw-cut lumber, though the joints are mortise and tenon, held with wooden pegs, evidence of the transition from timber framing to plank construction and circa 1890-1910. Unfortunately, unless the owner repairs the roof, the barn may be soon only a memory for this quaint Indiana village with its unusual name.

When barn scout Ron drove by this weathered barn in November, 2020, I asked him to stop, even though he didn’t know the owners. The barn had been neglected, its roof showing several holes, allowing dangerous watery penetration, although its weather vanes still protected against a lightning strike.

The barn sat near an intersection in Churusbusco, often referred to by locals as simply, “Busco.” The village lies near the headwaters of the Eel River in the extreme northeast corner of Whitley County, about 15 miles from Ft. Wayne, and represents Americana at its best: a population of under 2,000, a large town clock, two traffic lights, free parking along the storefronts, and a Citgo gas station.

Churubusco, named in honor of the 1847 Battle of Churubusco, which was fought in Mexico during the Mexican–American War, originally comprised two towns. Both were founded in the 19th century by European Americans – Union and Franklin, named after one of our founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin. They bordered each other across a railroad track. Prior to the 1840s, residents of the two towns had to travel 11 miles – by foot or horse and buggy – to Columbia City to get their mail. Eventually the towns grew enough to qualify for their own post office but, since they were in the same location, the government ordered them to apply for a joint post office. They couldn’t use their names since both were used elsewhere in the state.

At a joint community meeting, local school teacher Eliza Rich suggested merging the two towns and adopting the name, Churubusco, since the battle, only a year earlier, resulted in a decisive American victory, instilling as much patriotism as the names, Union and Franklin. The Churubusco post office has been in operation since 1848. The Spanish name refers to temple that commemorates the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli. The area is bordered by the river, Churusbusco, in Mexico City.

I liked the barn, whose red paint has faded to gray and whose green shingled roof has seen better days. However, at one time, the farmer must have been doing well since the adjacent milk house has a matching green roof. Inside, the post and beam construction is primarily saw-cut lumber, though the joints are mortise and tenon, held with wooden pegs, evidence of the transition from timber framing to plank construction and circa 1890-1910. Unfortunately, unless the owner repairs the roof, the barn may be soon only a memory for this quaint Indiana village with its unusual name.

Over the years, my paintings have been sold during the Whitley County Fair to raise funds for the impressive agricultural museum in Columbia City. The following paintings will be auctioned during the 2021 county fair in Columbia City.

“Photogenic”

On our November, 2018, barn tour – on a bone-chillingly cold day – I asked Ron to stop at this old barn, a striking scene. Weeds and several hay bales sat in the foreground, while large hardwood trees framed the barn and a storage shed. A reddish tank silhouetted against a backdrop of trees, their colors muted in the distance. The barn’s metal roof, a bit warped here and there, had done its duty: the structure appeared to be stable – as did the massive silo. It was a composition I could paint again and again and never get tired of it.

Unfortunately, with time constraints and frigid temperatures, Ron and I didn’t knock on the farmhouse door, hoping that we’d be able to contact the owners later. I’m sure there’s a story or two just waiting to be discovered.

On our November, 2018, barn tour – on a bone-chillingly cold day – I asked Ron to stop at this old barn, a striking scene. Weeds and several hay bales sat in the foreground, while large hardwood trees framed the barn and a storage shed. A reddish tank silhouetted against a backdrop of trees, their colors muted in the distance. The barn’s metal roof, a bit warped here and there, had done its duty: the structure appeared to be stable – as did the massive silo. It was a composition I could paint again and again and never get tired of it.

Unfortunately, with time constraints and frigid temperatures, Ron and I didn’t knock on the farmhouse door, hoping that we’d be able to contact the owners later. I’m sure there’s a story or two just waiting to be discovered.

“The Crosley Collector”

Even though I painted this 19th-century barn year ago, I took a different approach this time, featuring the old rusted auto in the foreground and placing the barn in the background. After all, the vehicle was a Crosley, which goes back to my hometown of Cincinnati and Paul Crosley, Jr., inventor of this auto and the entrepreneur who started WLW radio, the far-reaching voice of the Midwest. And, it’s hard not to love this vintage car, which, like old barns, represents a time in America when life was much different than today’s world.

The Crosley sat there patiently for me to sketch it and take reference photos in November, 2018. I found out, after talking with Beverly Yingst recently, that it’s now gone – into rehab, thanks to her husband Ned, who owns the farm with his wife. A Crosley aficionado, Ned restores these old cars in his barn, a passion that traces back to his youth when he saw the cars being built in 1946 in the nearby Marion, Indiana, plant. Crosley car production reached its peak of 25,000 per year in 1948. Four years later the dream ended. Still, the old cars are out there, as Bev advised me. “If you run across any in your travels,” she said, “please let us know. Ned loves to restore them.”

Thanks to Bev and Ned, the barn’s original siding frames this painting, adding a bit of antiquity to the piece. A few years ago Ned resided part of the barn, taking advantage of an offer at the state fair in Indianapolis. Ned took local wood to the fair and had it cut into siding in the sawmill in pioneer village. That was much more authentic than buying it at Home Depot; plus the old siding could be repurposed into frames for rustic barn paintings. And, for all those car buffs and barn lovers, this painting remembers two gems, preserving two more pieces of our vanishing landscape.

Even though I painted this 19th-century barn year ago, I took a different approach this time, featuring the old rusted auto in the foreground and placing the barn in the background. After all, the vehicle was a Crosley, which goes back to my hometown of Cincinnati and Paul Crosley, Jr., inventor of this auto and the entrepreneur who started WLW radio, the far-reaching voice of the Midwest. And, it’s hard not to love this vintage car, which, like old barns, represents a time in America when life was much different than today’s world.

The Crosley sat there patiently for me to sketch it and take reference photos in November, 2018. I found out, after talking with Beverly Yingst recently, that it’s now gone – into rehab, thanks to her husband Ned, who owns the farm with his wife. A Crosley aficionado, Ned restores these old cars in his barn, a passion that traces back to his youth when he saw the cars being built in 1946 in the nearby Marion, Indiana, plant. Crosley car production reached its peak of 25,000 per year in 1948. Four years later the dream ended. Still, the old cars are out there, as Bev advised me. “If you run across any in your travels,” she said, “please let us know. Ned loves to restore them.”

Thanks to Bev and Ned, the barn’s original siding frames this painting, adding a bit of antiquity to the piece. A few years ago Ned resided part of the barn, taking advantage of an offer at the state fair in Indianapolis. Ned took local wood to the fair and had it cut into siding in the sawmill in pioneer village. That was much more authentic than buying it at Home Depot; plus the old siding could be repurposed into frames for rustic barn paintings. And, for all those car buffs and barn lovers, this painting remembers two gems, preserving two more pieces of our vanishing landscape.

Orange County

“The Wallet” – Castle Knoll Farms, Paoli

In September, 2016, it was my wife’s turn to pick a surprise destination for our annual anniversary trip. She chose French Lick, Indiana – about three hours from home. Before we arrived at our hotel in French Lick, we went on an “elephant encounter” at Wilstem Ranch, a few miles south of town. Laura had scheduled an ATV ride for us, which took us through acres of rolling hills, up and down rocky ravines, and past this old dairy barn, one of several on the adjacent Castle Knoll Farm.

The scene, a green-roofed barn set against a field of yellow hay, high on a hill, with several other lesser barns in the distance, caught my attention. I asked the guide to stop so that I could take a photo with my phone, which I kept safe in my shorts pocket, zipped shut. It turned out so well that I considered painting it. Click here for the rest of this story - a message about going from poverty to great wealth in the 1920s, allowing Edward Ballard to build these barns on his cattle farm. However, as he discovered, all that glitters is not gold.

In September, 2016, it was my wife’s turn to pick a surprise destination for our annual anniversary trip. She chose French Lick, Indiana – about three hours from home. Before we arrived at our hotel in French Lick, we went on an “elephant encounter” at Wilstem Ranch, a few miles south of town. Laura had scheduled an ATV ride for us, which took us through acres of rolling hills, up and down rocky ravines, and past this old dairy barn, one of several on the adjacent Castle Knoll Farm.

The scene, a green-roofed barn set against a field of yellow hay, high on a hill, with several other lesser barns in the distance, caught my attention. I asked the guide to stop so that I could take a photo with my phone, which I kept safe in my shorts pocket, zipped shut. It turned out so well that I considered painting it. Click here for the rest of this story - a message about going from poverty to great wealth in the 1920s, allowing Edward Ballard to build these barns on his cattle farm. However, as he discovered, all that glitters is not gold.

Washington County

“Private George Beck”

This grist mill, nobly restored by a group of passionate historians, lies near Salem in southern Indiana. It traces back to George Beck, a private in the Revolutionary War, an early American hero.

Private George Beck, as many of the fellow colonists, served in the Continental Army to defeat our English landlords in the late 1770s. He, his wife Elizabeth, and their seven children lived in North Carolina but they yearned for more land, feeling the urge to travel west and use his war grant for land. So, Beck and his family left Roan, North Carolina, and traveled to southern Indiana in the fall of 1807. They settled near a river, which they called the Blue River, a handle that has stuck, named for its blue color that first snowy winter. One day while hunting coons, George and his sons discovered a natural spring and thought it would be a good place for a grist mill.

They built a 15 by 15-foot building, quarried local “iron stone” from a quarter mile away and constructed a dam inside the spring’s opening. They built a waterway through hollow logs to a paddle wheel, allowing them to grind corn by August of 1808.

The mill attracted many new settlers and, with increased prosperity, the family added a sawmill later in 1808. But this was not a peaceful time. Many Indian tribes lived in western Ohio and Indiana in this era and sided with the British in the War of 1812. Accordingly, two forts were built close to the mill to provide protection.

As the years passed, apparently there were enough sheep farmers in the region to merit the mill adding a wool carding machine in 1822 – the rare original still preserved – and a wool picker, a device to clean newly shorn wool. With the Beck’s financial position improving and demand for mill services increasing, the family built a larger mill in 1826 and, in 1864, yet another entire mill – the one present today. The Beck family ran the operation until approximately 1950. In 2005 Joyce Anderson, a Beck family descendant, and her husband Don donated the mill and 14 acres to the Friends of Beck’s Mill, a non-profit organization that has restored the building and has opened it as a working mill to the public. The spring from Beck’s Cave flows again!

This grist mill, nobly restored by a group of passionate historians, lies near Salem in southern Indiana. It traces back to George Beck, a private in the Revolutionary War, an early American hero.

Private George Beck, as many of the fellow colonists, served in the Continental Army to defeat our English landlords in the late 1770s. He, his wife Elizabeth, and their seven children lived in North Carolina but they yearned for more land, feeling the urge to travel west and use his war grant for land. So, Beck and his family left Roan, North Carolina, and traveled to southern Indiana in the fall of 1807. They settled near a river, which they called the Blue River, a handle that has stuck, named for its blue color that first snowy winter. One day while hunting coons, George and his sons discovered a natural spring and thought it would be a good place for a grist mill.

They built a 15 by 15-foot building, quarried local “iron stone” from a quarter mile away and constructed a dam inside the spring’s opening. They built a waterway through hollow logs to a paddle wheel, allowing them to grind corn by August of 1808.

The mill attracted many new settlers and, with increased prosperity, the family added a sawmill later in 1808. But this was not a peaceful time. Many Indian tribes lived in western Ohio and Indiana in this era and sided with the British in the War of 1812. Accordingly, two forts were built close to the mill to provide protection.

As the years passed, apparently there were enough sheep farmers in the region to merit the mill adding a wool carding machine in 1822 – the rare original still preserved – and a wool picker, a device to clean newly shorn wool. With the Beck’s financial position improving and demand for mill services increasing, the family built a larger mill in 1826 and, in 1864, yet another entire mill – the one present today. The Beck family ran the operation until approximately 1950. In 2005 Joyce Anderson, a Beck family descendant, and her husband Don donated the mill and 14 acres to the Friends of Beck’s Mill, a non-profit organization that has restored the building and has opened it as a working mill to the public. The spring from Beck’s Cave flows again!

KENTUCKY

Casey County

“Ruffled Grouse Society”

Some commissions are better than others and this was one of the better ones. Gretchen, the development officer for Cancer Free Kids, contacted me after I donated one of my barn paintings to her foundation’s fundraiser in 2018. She wanted to surprise her boyfriend Greg with a painting of his family’s barn, deep in the hills of Casey County. After taking a hunting trip there in November, she brought back a few good photos at twilight as well as gnarled wood siding from the barn, which I used for framing the painting.

A woman hunting? When I first talked with her, I found it hard to believe that she would enjoy hunting in the cold rain of northern Michigan in October. Later, when we met, she told me that she had been a rock climber. Yes, the kind I read about in Outside, a magazine geared towards the young and adventurous, who seem to thrive only on dangerous activities that invite the potential of death. Gretchen had been one of them in her younger years. Now she focuses “only” on hunting.

When I helped unload the barn wood from her car, I noticed a sticker, “Ruffled Grouse Society,” a group that is made up of “mainly grouse and woodcock hunters who support national scientific conservation and management efforts to ensure the future of the species,” as its website explains. She and Greg are both members.

The composition was a good one, thanks to Gretchen’s photo showing the barn on a hillside, with the old farmhouse on the left and a pond in front. It represents a piece of Kentucky history, tracing back to 1859 when Andrew MacDowell Wethington established the farm. Greg’s great grandfather, Cleatus Wethington and his wife Etta had eight children, typical for farm families in those days since the entire family worked the farm: the more children, the merrier. Irvine, the oldest son, served in the Navy, but died of pneumonia in 1921. With the five thousand dollar government payment for his death, the family built a new farm house and put the rest towards building this barn in 1924.

The farm passed down to Greg’s grandfather Andrew who, with his wife Odelia and their eight children, continued farming, raising tobacco as the cash crop. Self-sustaining, they survived the Great Depression with their large vegetable garden, cows for milk, chickens for eggs, and hogs for meat. Since the 1980s when Andrew retired, his adult children have continued to hold on to the farm. Uncle Jim and cousin Jimmy raise hay and cattle on the 100 acres. They also maintain and old one-room schoolhouse, the Sulfer Run School House, where Aunt Lucille taught Greg’s mom.

At the “unveiling” party – when Greg got his painting – he mentioned that the barn is located on top of a hill, not far from Dry Creek, a name that would have fit the painting. But Ruffled Grouse Society wasn’t a bad choice. The hunters liked it.

Some commissions are better than others and this was one of the better ones. Gretchen, the development officer for Cancer Free Kids, contacted me after I donated one of my barn paintings to her foundation’s fundraiser in 2018. She wanted to surprise her boyfriend Greg with a painting of his family’s barn, deep in the hills of Casey County. After taking a hunting trip there in November, she brought back a few good photos at twilight as well as gnarled wood siding from the barn, which I used for framing the painting.

A woman hunting? When I first talked with her, I found it hard to believe that she would enjoy hunting in the cold rain of northern Michigan in October. Later, when we met, she told me that she had been a rock climber. Yes, the kind I read about in Outside, a magazine geared towards the young and adventurous, who seem to thrive only on dangerous activities that invite the potential of death. Gretchen had been one of them in her younger years. Now she focuses “only” on hunting.

When I helped unload the barn wood from her car, I noticed a sticker, “Ruffled Grouse Society,” a group that is made up of “mainly grouse and woodcock hunters who support national scientific conservation and management efforts to ensure the future of the species,” as its website explains. She and Greg are both members.

The composition was a good one, thanks to Gretchen’s photo showing the barn on a hillside, with the old farmhouse on the left and a pond in front. It represents a piece of Kentucky history, tracing back to 1859 when Andrew MacDowell Wethington established the farm. Greg’s great grandfather, Cleatus Wethington and his wife Etta had eight children, typical for farm families in those days since the entire family worked the farm: the more children, the merrier. Irvine, the oldest son, served in the Navy, but died of pneumonia in 1921. With the five thousand dollar government payment for his death, the family built a new farm house and put the rest towards building this barn in 1924.

The farm passed down to Greg’s grandfather Andrew who, with his wife Odelia and their eight children, continued farming, raising tobacco as the cash crop. Self-sustaining, they survived the Great Depression with their large vegetable garden, cows for milk, chickens for eggs, and hogs for meat. Since the 1980s when Andrew retired, his adult children have continued to hold on to the farm. Uncle Jim and cousin Jimmy raise hay and cattle on the 100 acres. They also maintain and old one-room schoolhouse, the Sulfer Run School House, where Aunt Lucille taught Greg’s mom.

At the “unveiling” party – when Greg got his painting – he mentioned that the barn is located on top of a hill, not far from Dry Creek, a name that would have fit the painting. But Ruffled Grouse Society wasn’t a bad choice. The hunters liked it.

Marion County

“A Slave’s Pride”

How we connect with people can be fascinating and it sometimes makes me feel that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, life is one big play and we’re all actors, merely following our scripts. In September, 2016, on our annual “surprise” anniversary trip, Laura chose French Lick, Indiana, a historic resort nestled in rural southern Indiana.

For entertainment, she scheduled a three-hour ride on an old train line, taking us through the countryside while the guide gave us glimpses into Indiana history as we rode along. She made sure it was handicap accessible since she was struggling to walk at the time. Yes, the train was accommodating, but required us to sit in the last section where Laura could be raised up on a lift to get into the train. We sat in the first seat, next to and around three young black couples. Do you see where this is going? No, you don’t. Click here for the rest of this interesting story.

How we connect with people can be fascinating and it sometimes makes me feel that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, life is one big play and we’re all actors, merely following our scripts. In September, 2016, on our annual “surprise” anniversary trip, Laura chose French Lick, Indiana, a historic resort nestled in rural southern Indiana.

For entertainment, she scheduled a three-hour ride on an old train line, taking us through the countryside while the guide gave us glimpses into Indiana history as we rode along. She made sure it was handicap accessible since she was struggling to walk at the time. Yes, the train was accommodating, but required us to sit in the last section where Laura could be raised up on a lift to get into the train. We sat in the first seat, next to and around three young black couples. Do you see where this is going? No, you don’t. Click here for the rest of this interesting story.

“A Slave’s Pride II”

In my visit to Gethsemani in 2017, I delivered paintings for a fundraiser for Maggie’s abuse shelter, met Maggie and her sister Patty, and got a tour of the farm with Maggie’s brother Joe. He took us to the top of the hill where the second barn still stands and then took Sister Eleanor, from the nearby Sisters of Loretto, to the location of the original complex founded by Fr. Charlex Nerinckx in the early 1800s. This became the start of the Sisters of Loretto, but the summer’s growth of six-foot high weeds prevented us from walking to the few remaining stone foundations of the original six log cabins, strategically built near a natural spring that flows into Hardin Creek.

Joe’s mom was a Smith and her grandfather was Austin Smith, who was the patriarch of this farm and a former slave here in the 1860s. Joe’s father, William Roger Thompson, Sr., came here from an area known as “poortown blacks,” in Washington County near Springfield. He gave half of the farm to Joe and the other half to his seven siblings.

Joe’s father, William Thompson, Sr., built this tobacco barn in 1970 with saw-cut lumber reclaimed from another barn. Joe, his wife, and his brother worked the land, hand-cutting four acres of tobacco and storing it in the barn. But, when congress enacted restrictions, farming tobacco became less profitable and the family stopped raising it in 2007.

Joe’s family continued working the land, converting it into a dairy farm. But, pressured by more state and federal regulations, the family ended their dairy business in 2012. Today they raise livestock – a bull and seven cows – and a lot of chickens that scamper about continually.

In 2018 I delivered this painting and one of the original log cabin – located not far from the barn – that was the early beginning of the Sisters of Loretto in 1812. Maggie will use them in a fundraiser for her church, St. Charles, founded in 1786, which sits on a hill, overlooking her farm. I also donated a painting of a barn at Loretto to Pam Grundy, who will use it in a fundraiser for her church, Holy Rosary, another chiefly black Catholic congregation.

However, even though these two barns are in their final years, their history will live on through my paintings as well as stories passed down to further Thompson and Burton generations.

In my visit to Gethsemani in 2017, I delivered paintings for a fundraiser for Maggie’s abuse shelter, met Maggie and her sister Patty, and got a tour of the farm with Maggie’s brother Joe. He took us to the top of the hill where the second barn still stands and then took Sister Eleanor, from the nearby Sisters of Loretto, to the location of the original complex founded by Fr. Charlex Nerinckx in the early 1800s. This became the start of the Sisters of Loretto, but the summer’s growth of six-foot high weeds prevented us from walking to the few remaining stone foundations of the original six log cabins, strategically built near a natural spring that flows into Hardin Creek.

Joe’s mom was a Smith and her grandfather was Austin Smith, who was the patriarch of this farm and a former slave here in the 1860s. Joe’s father, William Roger Thompson, Sr., came here from an area known as “poortown blacks,” in Washington County near Springfield. He gave half of the farm to Joe and the other half to his seven siblings.

Joe’s father, William Thompson, Sr., built this tobacco barn in 1970 with saw-cut lumber reclaimed from another barn. Joe, his wife, and his brother worked the land, hand-cutting four acres of tobacco and storing it in the barn. But, when congress enacted restrictions, farming tobacco became less profitable and the family stopped raising it in 2007.

Joe’s family continued working the land, converting it into a dairy farm. But, pressured by more state and federal regulations, the family ended their dairy business in 2012. Today they raise livestock – a bull and seven cows – and a lot of chickens that scamper about continually.

In 2018 I delivered this painting and one of the original log cabin – located not far from the barn – that was the early beginning of the Sisters of Loretto in 1812. Maggie will use them in a fundraiser for her church, St. Charles, founded in 1786, which sits on a hill, overlooking her farm. I also donated a painting of a barn at Loretto to Pam Grundy, who will use it in a fundraiser for her church, Holy Rosary, another chiefly black Catholic congregation.

However, even though these two barns are in their final years, their history will live on through my paintings as well as stories passed down to further Thompson and Burton generations.

Nelson County

"Gethsemani Red"

Located in rural Nelson County, about 45 minutes south-east of Louisville, the Abbey of Gethsemani's monks have farmed here for over 150 years. Founded in 1848 by Trappist monks from France, the abbey offers unstructured retreats to the public, which I've taken for over 20 years. Finally, I decided to paint their red barn, which sits on monastic grounds, not open to the public. As it should be.

Father Louis, aka Thomas Merton, a convert to the Catholic faith, wrote his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, in 1946, five years after he entered the monastery. Merton, a Columbia University graduate, did this at the request of his abbot, and, through a friend in New York City, got it published, though the publisher regarded it as a high risk. Millions of copies later, it became the best selling book ever published by that company.

Merton also wrote many other books and, if he had not died accidentally in 1968, would have become even more well-read around the world. His book, Seeds of Contemplation, became my bible in my younger years, and, eventually drew me to this holy place. This painting was donated to the Abbey.

Located in rural Nelson County, about 45 minutes south-east of Louisville, the Abbey of Gethsemani's monks have farmed here for over 150 years. Founded in 1848 by Trappist monks from France, the abbey offers unstructured retreats to the public, which I've taken for over 20 years. Finally, I decided to paint their red barn, which sits on monastic grounds, not open to the public. As it should be.

Father Louis, aka Thomas Merton, a convert to the Catholic faith, wrote his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, in 1946, five years after he entered the monastery. Merton, a Columbia University graduate, did this at the request of his abbot, and, through a friend in New York City, got it published, though the publisher regarded it as a high risk. Millions of copies later, it became the best selling book ever published by that company.

Merton also wrote many other books and, if he had not died accidentally in 1968, would have become even more well-read around the world. His book, Seeds of Contemplation, became my bible in my younger years, and, eventually drew me to this holy place. This painting was donated to the Abbey.

MAINE

“Wabanaki”

Ohio’s statehood goes back to 1803, but the land that this Maine barn sits on traces to 200 years earlier when it belonged to the Wabanaki Indians, who established villages here in 1606. They preceded the Mayflower pilgrims, the Puritans, who arrived in nearby Massachusetts in 1620, founding the second successful English settlement in America, and later, in 1675 in King Philip’s War and in 1688 in King William’s War, they may have fought against descendants of these colonists.

In October, 2018, I drove past this delightful New England barn, nearly hidden in a pesky cold rain and partly obscured by trees beginning to turn colors. My college roommate, Dr. Pat Lang, and I were driving to Mt. Desert Island, where I planned to run a marathon. A few days later, after the race, rated as America’s most scenic marathon – and rightfully so – we retraced our steps and stopped here, hoping to find the owner. But no one was home.

The smaller barn in the foreground was probably the older of the two, likely dating to the 1800s. The larger one, about twice the size of its neighbor, stretched well into the woods and hadn’t been converted into living quarters as its elder had: windows and chimneys told the story. Its metal cupola, imprinted with an infinity-styled design, featured a directional weather-vane that was still in good condition. The chimney ran into a small add-on building that seemed out of place, except to provide room for a fireplace. Above the building was an interesting square metal tile with rays jutting out like feathers on a peacock. A tiny red escape ladder was attached, leading from the upper window to the lower one, providing an option in case of fire, not a bad idea since the weathered wood, its paint peeling, would be no match for a lightning strike. Though it’s old, the barn would have been impressive in the days of the Puritans and the Wabanaki. In fact, it impressed me enough to stop. I’m glad we did.

Ohio’s statehood goes back to 1803, but the land that this Maine barn sits on traces to 200 years earlier when it belonged to the Wabanaki Indians, who established villages here in 1606. They preceded the Mayflower pilgrims, the Puritans, who arrived in nearby Massachusetts in 1620, founding the second successful English settlement in America, and later, in 1675 in King Philip’s War and in 1688 in King William’s War, they may have fought against descendants of these colonists.

In October, 2018, I drove past this delightful New England barn, nearly hidden in a pesky cold rain and partly obscured by trees beginning to turn colors. My college roommate, Dr. Pat Lang, and I were driving to Mt. Desert Island, where I planned to run a marathon. A few days later, after the race, rated as America’s most scenic marathon – and rightfully so – we retraced our steps and stopped here, hoping to find the owner. But no one was home.

The smaller barn in the foreground was probably the older of the two, likely dating to the 1800s. The larger one, about twice the size of its neighbor, stretched well into the woods and hadn’t been converted into living quarters as its elder had: windows and chimneys told the story. Its metal cupola, imprinted with an infinity-styled design, featured a directional weather-vane that was still in good condition. The chimney ran into a small add-on building that seemed out of place, except to provide room for a fireplace. Above the building was an interesting square metal tile with rays jutting out like feathers on a peacock. A tiny red escape ladder was attached, leading from the upper window to the lower one, providing an option in case of fire, not a bad idea since the weathered wood, its paint peeling, would be no match for a lightning strike. Though it’s old, the barn would have been impressive in the days of the Puritans and the Wabanaki. In fact, it impressed me enough to stop. I’m glad we did.

MASSACHUSETTS

"Galenski's Gem"

This painting is framed in original chestnut barn wood dating to perhaps the late 1700s or early 1800s. My college roommate, who lives in Deerfield, Massachusetts, was permitted to hunt in swampy ground near the "original" barn near a river bank on this farm. He found a mortised chestnut beam, 8x8 inches square, extracted it from the muck with the aid of a jack, and using his impressive woodworking skills, made a charming frame for this painting. The barn's story is even more interesting. In Ohio, old means 1800s; but in western Massachusetts old means 1600s.

This painting is framed in original chestnut barn wood dating to perhaps the late 1700s or early 1800s. My college roommate, who lives in Deerfield, Massachusetts, was permitted to hunt in swampy ground near the "original" barn near a river bank on this farm. He found a mortised chestnut beam, 8x8 inches square, extracted it from the muck with the aid of a jack, and using his impressive woodworking skills, made a charming frame for this painting. The barn's story is even more interesting. In Ohio, old means 1800s; but in western Massachusetts old means 1600s.

Montana

Flathead County

“Kalispell”

If Ohio represents the Midwest, its pioneer farmers of the late 1700s and early 1800s, then Montana represents the West, land that Lewis and Clark explored in 1804, home to American Indian tribes, cowboys, Indian wars, the gold rush of the 1860s, lawmen, and desperados, and wild animals that used to exist in pre-1700 Ohio – the buffalo, elk, cougar, bear, and antelope. Yes, Montana is the West of today, much more so than any of the other western states. There’s no Dallas or Houston here, no Phoenix or Salt Lake City or Denver. Montana’s largest city is Billings – with a population of just over 110,000. That peanuts to a Texan. But it’s the real West – raw, sparsely populated, unspoiled, wild. People here are honest, dependable, and rugged. To survive 100 degree heat of the summer and 40 below zero in the winter demands toughness. Surviving a grizzly bear attack demands the same.

On a trip my college roommate and I took in the summer of 2017, retracing our steps from 1972, the summer before our last year in school – when we drove here and other parts west, sleeping on the ground in KOA camps in my tiny tent from boy scout days – we found the people of Montana not only exceptionally friendly but also enthusiastic. Maybe that’s because their summers are so beautiful, but maybe they’re that way in the winter as well. Click here for the rest of this story.

“Kalispell”

If Ohio represents the Midwest, its pioneer farmers of the late 1700s and early 1800s, then Montana represents the West, land that Lewis and Clark explored in 1804, home to American Indian tribes, cowboys, Indian wars, the gold rush of the 1860s, lawmen, and desperados, and wild animals that used to exist in pre-1700 Ohio – the buffalo, elk, cougar, bear, and antelope. Yes, Montana is the West of today, much more so than any of the other western states. There’s no Dallas or Houston here, no Phoenix or Salt Lake City or Denver. Montana’s largest city is Billings – with a population of just over 110,000. That peanuts to a Texan. But it’s the real West – raw, sparsely populated, unspoiled, wild. People here are honest, dependable, and rugged. To survive 100 degree heat of the summer and 40 below zero in the winter demands toughness. Surviving a grizzly bear attack demands the same.

On a trip my college roommate and I took in the summer of 2017, retracing our steps from 1972, the summer before our last year in school – when we drove here and other parts west, sleeping on the ground in KOA camps in my tiny tent from boy scout days – we found the people of Montana not only exceptionally friendly but also enthusiastic. Maybe that’s because their summers are so beautiful, but maybe they’re that way in the winter as well. Click here for the rest of this story.

WYOMING

“A Moveable Feast”

Hemingway wrote these words about his time in Paris in his book, A Moveable Feast, “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

My son Jon, his wife Audrey, and their son Colin lived in Salt Lake City, a town surrounded by the towering mountains of Utah, for two years. And so, wherever they go, the West will always be with them since the West is also a moveable feast.

This barn, an old one built by a Mormon pioneer family named Moulton, is located in Mormon Row, just south of the Teton range in Wyoming. These Mormon pioneers did not come from the east, but rather from the west, traveling here from Idaho in the 1890s. This collection of homes and barns is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. It's also known as Antelope Flats, the area lies between the towns of Moose and Kelly. There’s plenty to see here: historic buildings, herds of buffalo, and the snow-covered Tetons rising in the background.

Hemingway wrote these words about his time in Paris in his book, A Moveable Feast, “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

My son Jon, his wife Audrey, and their son Colin lived in Salt Lake City, a town surrounded by the towering mountains of Utah, for two years. And so, wherever they go, the West will always be with them since the West is also a moveable feast.

This barn, an old one built by a Mormon pioneer family named Moulton, is located in Mormon Row, just south of the Teton range in Wyoming. These Mormon pioneers did not come from the east, but rather from the west, traveling here from Idaho in the 1890s. This collection of homes and barns is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. It's also known as Antelope Flats, the area lies between the towns of Moose and Kelly. There’s plenty to see here: historic buildings, herds of buffalo, and the snow-covered Tetons rising in the background.