THE OHIO BARN PROJECT

Paintings Listed by Ohio County - D-I

DARKE

"Snowbound"

According to Gretchen Snyder, who owns this farm with her husband Chris, this barn is one of seven on the property, which they purchased in 2007. Seven barns meant that the original farm had to be large and that the farmer was prosperous. This barn with its massive hand-hewn beams, built in 1872 by Joseph Glunt, was likely the first barn on the farm. Later, in 1884, S.C. and Mary Glunt Mote built the farmhouse, which the Synders are currently rehabbing.

Though I visited this barn in April, when the scene was snow-less and not yet spring-like, I felt compelled to paint the barn in winter – thanks to a photo from the owners, reminding me of Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl, a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, which he published in 1866. In that era, Ohio was emerging from the Civil War, was mostly a state of farms with hand-hewn timber-framed barns, and was full of hardy souls with large families. I’m sure that many of those pioneers could identify with this poem. Six years later the Glunts built this barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

According to Gretchen Snyder, who owns this farm with her husband Chris, this barn is one of seven on the property, which they purchased in 2007. Seven barns meant that the original farm had to be large and that the farmer was prosperous. This barn with its massive hand-hewn beams, built in 1872 by Joseph Glunt, was likely the first barn on the farm. Later, in 1884, S.C. and Mary Glunt Mote built the farmhouse, which the Synders are currently rehabbing.

Though I visited this barn in April, when the scene was snow-less and not yet spring-like, I felt compelled to paint the barn in winter – thanks to a photo from the owners, reminding me of Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl, a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, which he published in 1866. In that era, Ohio was emerging from the Civil War, was mostly a state of farms with hand-hewn timber-framed barns, and was full of hardy souls with large families. I’m sure that many of those pioneers could identify with this poem. Six years later the Glunts built this barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

DEFIANCE

“North by Northwest”

After driving for a few hours north on the ever-so-straight Route 127, I veered westwards on Route 18, hoping to find a barn in the small section of Defiance County that I’d pass through. And I was lucky to spot this one, a red beauty, nicely maintained, and just off the main road. This true bank barn was built into a gentle rise and supported in the rear by sturdy stone walls. Though it was cold and windy, the snowfall had stopped, giving me a chance to do a sketch and take reference photos. I liked the composition and figured I’d contact the historical society later on to learn more about it. It’s located west of the county seat, Defiance, which takes its name – as the county does – from a fort that General “Mad” Anthony Wayne built in August, 1794. Though it was considered one of the strongest fortifications of that period, it took only nine days to build and was strategically placed in between two major rivers, the Maumee and the Auglaize. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

After driving for a few hours north on the ever-so-straight Route 127, I veered westwards on Route 18, hoping to find a barn in the small section of Defiance County that I’d pass through. And I was lucky to spot this one, a red beauty, nicely maintained, and just off the main road. This true bank barn was built into a gentle rise and supported in the rear by sturdy stone walls. Though it was cold and windy, the snowfall had stopped, giving me a chance to do a sketch and take reference photos. I liked the composition and figured I’d contact the historical society later on to learn more about it. It’s located west of the county seat, Defiance, which takes its name – as the county does – from a fort that General “Mad” Anthony Wayne built in August, 1794. Though it was considered one of the strongest fortifications of that period, it took only nine days to build and was strategically placed in between two major rivers, the Maumee and the Auglaize. The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

DELAWARE

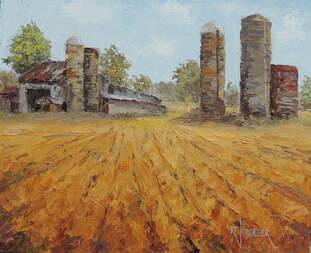

“The Grandfathers”

Years ago, when I first laid eyes on this barn while driving north on Ohio Route 3 and just outside of Sunbury, I was captivated. The morning mist hung on the ground, gentle rays of sun flickered, and the weathered barn, its rusting metal roof, and its five silos almost seemed to be rising out of the fog. The scene was haunting and, a mile later, I regretted not stopping to sketch it but, at the same time, I didn’t want to be late for friend’s wedding. I vowed to return.When I paid a visit the next spring, I walked around, admiring the ruins of what must been a large and prosperous Ohio farm. But now the silos were empty, the buildings unoccupied, and there was no clue to ownership or history – just a marvelous composition. I called the county auditor, providing this address and another of a barn down the road, but didn’t get any response to my letter. The historical society couldn’t help, either. But the barn begged to be painted, regardless of its anonymity. And there’s a story, too.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Years ago, when I first laid eyes on this barn while driving north on Ohio Route 3 and just outside of Sunbury, I was captivated. The morning mist hung on the ground, gentle rays of sun flickered, and the weathered barn, its rusting metal roof, and its five silos almost seemed to be rising out of the fog. The scene was haunting and, a mile later, I regretted not stopping to sketch it but, at the same time, I didn’t want to be late for friend’s wedding. I vowed to return.When I paid a visit the next spring, I walked around, admiring the ruins of what must been a large and prosperous Ohio farm. But now the silos were empty, the buildings unoccupied, and there was no clue to ownership or history – just a marvelous composition. I called the county auditor, providing this address and another of a barn down the road, but didn’t get any response to my letter. The historical society couldn’t help, either. But the barn begged to be painted, regardless of its anonymity. And there’s a story, too.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

ERIE

“Prisoners of War”

In the spring of 2018 – a year before my barn tour of Erie County – my barn scout Mel sent me a photo of this unusual barn and told me its story, which was the first time I’d heard that the United States took in POWs during WWII. But let’s begin at the beginning.

The barn – now dismantled – had a slate roof with the date of 1901, probably signifying when the barn was built. The farm may have been started earlier than that, as many were in Ohio’s northwest. And the original family may have been the Ohlemachers.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

In the spring of 2018 – a year before my barn tour of Erie County – my barn scout Mel sent me a photo of this unusual barn and told me its story, which was the first time I’d heard that the United States took in POWs during WWII. But let’s begin at the beginning.

The barn – now dismantled – had a slate roof with the date of 1901, probably signifying when the barn was built. The farm may have been started earlier than that, as many were in Ohio’s northwest. And the original family may have been the Ohlemachers.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

FAIRFIELD

“The Captain”

Liz Fox – along with her husband Bob, the barn owner – was kind enough to share with me information about the early days of this Ohio gem, information that comes from a copy of the diary of Captain August F. Witte. In his writing, Witte explained that he enlisted in the German military when he was 26, receiving the rank of corporal in the Landwehr Battalion. Within a year he rose to lieutenant. Then, as he wrote, he “marched with the Army of Hanover to the occupation of the Netherlands and was attached to the staff of Major General Lyon. In this way I fought against Napoleon and returned from France in February, 1816. In the year 1817 I was promotion to the rank of captain.” But perhaps the aura of the new world was calling him.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Liz Fox – along with her husband Bob, the barn owner – was kind enough to share with me information about the early days of this Ohio gem, information that comes from a copy of the diary of Captain August F. Witte. In his writing, Witte explained that he enlisted in the German military when he was 26, receiving the rank of corporal in the Landwehr Battalion. Within a year he rose to lieutenant. Then, as he wrote, he “marched with the Army of Hanover to the occupation of the Netherlands and was attached to the staff of Major General Lyon. In this way I fought against Napoleon and returned from France in February, 1816. In the year 1817 I was promotion to the rank of captain.” But perhaps the aura of the new world was calling him.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“The County Fair”

Signage, above several entrances to this circular barn, clearly states its history: Round Cattle Barn – Built in 1906 – By J.E. Hedges – Dairy Cattle. It’s a rarity – a round barn built specifically for a county fair.

Hedges, a local farmer and barn builder, could have chosen a traditional rectangular barn for this project, but this was an era when round barns were considered ideal for dairy cattle. For his labor and materials Hedges was paid $3,022.14, a huge sum in 1906. He cleverly soaked the lumber for the curved section in a creek and then was able to bend it into a circle. The barn, built for dairy and beef cattle, also housed the junior livestock sale.

With a diameter stretching to 95 feet and a roof covered with wood shingles, the sight must have commanded attention during the county fair in 1906. Apparently local residents began to appreciate the uniqueness of the barn and so they covered the roof with galvanized metal in 1934, assuring longevity. In 1937, with the fair’s popularity growing – despite the throes of the Great Depression – they added two large wings to the round barn.

What’s just as impressive as the barn is the county fair, which dates to 1851, the oldest continuously running county fair in Ohio. In 1850 the Fairfield County Agricultural Society formed and hosted the fair in Lancaster the following year. Only 60 years earlier Lancaster, the county seat, was comprised of 100 wigwams and 500 people. The fertile fields drew immigrants and agriculture was king. Indians moved westwards.

In 1876 the fairgrounds expanded to 22 acres and again to 36 acres in 1880, when a half-mile race track was added. Three years later organizers built a new amphitheatre and eventually drilled for natural gas. In 1889 they found it, tapping its energy to provide light for night-time races, the only place in America that offered night racing. They also piped the gas to the center of a lake in the fairgrounds and ignited it as it bubbled up through perforated pipes, earning the title, “Lake of Fire.” What a sight that must have been!

Another feather on this barn’s cap was that it was used in filming the 1980 movie, Brubaker, starring Robert Redford. Chances are that the film crew didn’t know much about J.E. Hedges but they liked his barn well enough to use it. I’m sure, if he were alive, he’d be proud. This painting sold in a fundraiser for the Fairfield County museums.

Signage, above several entrances to this circular barn, clearly states its history: Round Cattle Barn – Built in 1906 – By J.E. Hedges – Dairy Cattle. It’s a rarity – a round barn built specifically for a county fair.

Hedges, a local farmer and barn builder, could have chosen a traditional rectangular barn for this project, but this was an era when round barns were considered ideal for dairy cattle. For his labor and materials Hedges was paid $3,022.14, a huge sum in 1906. He cleverly soaked the lumber for the curved section in a creek and then was able to bend it into a circle. The barn, built for dairy and beef cattle, also housed the junior livestock sale.

With a diameter stretching to 95 feet and a roof covered with wood shingles, the sight must have commanded attention during the county fair in 1906. Apparently local residents began to appreciate the uniqueness of the barn and so they covered the roof with galvanized metal in 1934, assuring longevity. In 1937, with the fair’s popularity growing – despite the throes of the Great Depression – they added two large wings to the round barn.

What’s just as impressive as the barn is the county fair, which dates to 1851, the oldest continuously running county fair in Ohio. In 1850 the Fairfield County Agricultural Society formed and hosted the fair in Lancaster the following year. Only 60 years earlier Lancaster, the county seat, was comprised of 100 wigwams and 500 people. The fertile fields drew immigrants and agriculture was king. Indians moved westwards.

In 1876 the fairgrounds expanded to 22 acres and again to 36 acres in 1880, when a half-mile race track was added. Three years later organizers built a new amphitheatre and eventually drilled for natural gas. In 1889 they found it, tapping its energy to provide light for night-time races, the only place in America that offered night racing. They also piped the gas to the center of a lake in the fairgrounds and ignited it as it bubbled up through perforated pipes, earning the title, “Lake of Fire.” What a sight that must have been!

Another feather on this barn’s cap was that it was used in filming the 1980 movie, Brubaker, starring Robert Redford. Chances are that the film crew didn’t know much about J.E. Hedges but they liked his barn well enough to use it. I’m sure, if he were alive, he’d be proud. This painting sold in a fundraiser for the Fairfield County museums.

“The Diary”

This barn isn’t particularly old, built probably in the 1890s – from trees on the farm, fashioned into beams connected by mortise and tenon joints and wooden nails. And, with a colorful family history, it probably wasn’t the first barn built on this farm. But, although the bank barn may not rank in Ohio’s top ten of distinctive old barns, its story certainly is one of Ohio’s best.

Thanks to an article about my Ohio Barn Project in the Logan (Hocking County) newspaper, Robert Sharp asked his daughter Nancy Sharp-Ward to contact me. And, since the barn was located in Sugar Grove, just across the Hocking County line, I included it on my barn tour. Fortunately I met Nancy who showed me a diary written by one of her ancestors, one that could easily be made into a movie. But let’s begin even earlier. This story will be featured in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

This barn isn’t particularly old, built probably in the 1890s – from trees on the farm, fashioned into beams connected by mortise and tenon joints and wooden nails. And, with a colorful family history, it probably wasn’t the first barn built on this farm. But, although the bank barn may not rank in Ohio’s top ten of distinctive old barns, its story certainly is one of Ohio’s best.

Thanks to an article about my Ohio Barn Project in the Logan (Hocking County) newspaper, Robert Sharp asked his daughter Nancy Sharp-Ward to contact me. And, since the barn was located in Sugar Grove, just across the Hocking County line, I included it on my barn tour. Fortunately I met Nancy who showed me a diary written by one of her ancestors, one that could easily be made into a movie. But let’s begin even earlier. This story will be featured in my second book on historic Ohio barns.

“Diley’s Delight”

The historical society chose this barn to be my demonstration painting for their fundraiser in the summer of 2022. Though I didn’t visit it, I liked the image that society president Peggy sent: a handsome English three-bay threshing barn, its red paint fading to gray, a few missing boards, and a little man-door stuck in a corner, its hinges still intact. It was a classic historic Ohio barn, another gem in the cap of barn-rich Fairfield County.

According to Peggy, the barn has hand-hewn beams, which dates it to the 19th-century … and probably before 1890, when sawn-beams began to appear, signaling a transition from timber-framing to plank construction. In fact, the current owner has repurposed some of the beams into fireplace mantles.

The Diley family (spelled originally Diele or Diehle) left Germany for America around 1830, settling in Pennsylvania before moving to Fairfield County. By 1840, according to a census, they were living in Violet township with several children and by 1850 Charles Diley, the patriarch, owned land here. He died in 1857. His sons Charles and John became partners on an 80-acre farm for a few years.

Over the years, Charles bought more land in the township, which, after his death in 1909, was divided among his five heirs. Later that year, his youngest son, Martin Diley, purchased an 81-acre farm – with the barn on it – for $8,000. It remained in the Diley family until 1974, two years after Martin died. Ralph and Betty Miller purchased it. Fifty years later, the Millers sold it to Dorothy Southard and it became part of a more than 800-acre holding, currently owned by Michael Hummel in a family trust. According to Peggy, the barn has deteriorated significantly, and the owner does not know what will happen to it. Chances are that it will probably be taken down, especially since the property is valuable, located in the U.S. Route 33 Development Corridor.

Though this barn likely replaced one or more barns on the Diley farm, it represents a prosperous farm family, one of the early residents of Fairfield County. And, even though it may be gone soon, at one point this handsome barn was the pride of Violet Township and certainly could be viewed as “Diley’s Delight.”

The historical society chose this barn to be my demonstration painting for their fundraiser in the summer of 2022. Though I didn’t visit it, I liked the image that society president Peggy sent: a handsome English three-bay threshing barn, its red paint fading to gray, a few missing boards, and a little man-door stuck in a corner, its hinges still intact. It was a classic historic Ohio barn, another gem in the cap of barn-rich Fairfield County.

According to Peggy, the barn has hand-hewn beams, which dates it to the 19th-century … and probably before 1890, when sawn-beams began to appear, signaling a transition from timber-framing to plank construction. In fact, the current owner has repurposed some of the beams into fireplace mantles.

The Diley family (spelled originally Diele or Diehle) left Germany for America around 1830, settling in Pennsylvania before moving to Fairfield County. By 1840, according to a census, they were living in Violet township with several children and by 1850 Charles Diley, the patriarch, owned land here. He died in 1857. His sons Charles and John became partners on an 80-acre farm for a few years.

Over the years, Charles bought more land in the township, which, after his death in 1909, was divided among his five heirs. Later that year, his youngest son, Martin Diley, purchased an 81-acre farm – with the barn on it – for $8,000. It remained in the Diley family until 1974, two years after Martin died. Ralph and Betty Miller purchased it. Fifty years later, the Millers sold it to Dorothy Southard and it became part of a more than 800-acre holding, currently owned by Michael Hummel in a family trust. According to Peggy, the barn has deteriorated significantly, and the owner does not know what will happen to it. Chances are that it will probably be taken down, especially since the property is valuable, located in the U.S. Route 33 Development Corridor.

Though this barn likely replaced one or more barns on the Diley farm, it represents a prosperous farm family, one of the early residents of Fairfield County. And, even though it may be gone soon, at one point this handsome barn was the pride of Violet Township and certainly could be viewed as “Diley’s Delight.”

FAYETTE

"Fayette's Corn Barn"

This corn barn is one of Ohio’s historical treasures. And, it’s got a good story, too. In driving down I-71 one day, my wife and I spied it from the highway, not far from the Washington Court House interchange. From a distance, it looked like a round barn and it caught my attention. After contacting the city, I finally reached the current owner, Chris Jefferies, who has lived in the area since 1979 and told me he’s always admired the Krieger homestead as well as Carl Krieger’s farming expertise. Carl was one of the best farmers in the area.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This corn barn is one of Ohio’s historical treasures. And, it’s got a good story, too. In driving down I-71 one day, my wife and I spied it from the highway, not far from the Washington Court House interchange. From a distance, it looked like a round barn and it caught my attention. After contacting the city, I finally reached the current owner, Chris Jefferies, who has lived in the area since 1979 and told me he’s always admired the Krieger homestead as well as Carl Krieger’s farming expertise. Carl was one of the best farmers in the area.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

FRANKLIN

"Rosedale"

I was lucky. When I arrived at the Everal Barn, I couldn’t tell which county it was in – Delaware or Franklin. Hoping for the latter, I asked the volunteer in the office, formerly the 1870s farmhouse of the Everal family, who told me that the county line was only a block away. So, yes, this would be my Franklin County barn. Lucky me.

The farm’s name, Rosedale, derives from industrialist J. W. Everal’s second wife Rose, stepmother to his children after his first wife died, whom he wanted remembered when he christened the farm with this name in August, 1914. Six years later the Carpenter family bought the property, which eventually passed to the City of Westerville in 1978. Realizing its significance, city leaders kept and restored several of the buildings, creating a historical peek into life in the late 1800s. Other buildings, besides the farmhouse, include a milk house, a hen house, a smoke house, and a carriage house, under which was the butcher room where the family prepared meat for preserving.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

I was lucky. When I arrived at the Everal Barn, I couldn’t tell which county it was in – Delaware or Franklin. Hoping for the latter, I asked the volunteer in the office, formerly the 1870s farmhouse of the Everal family, who told me that the county line was only a block away. So, yes, this would be my Franklin County barn. Lucky me.

The farm’s name, Rosedale, derives from industrialist J. W. Everal’s second wife Rose, stepmother to his children after his first wife died, whom he wanted remembered when he christened the farm with this name in August, 1914. Six years later the Carpenter family bought the property, which eventually passed to the City of Westerville in 1978. Realizing its significance, city leaders kept and restored several of the buildings, creating a historical peek into life in the late 1800s. Other buildings, besides the farmhouse, include a milk house, a hen house, a smoke house, and a carriage house, under which was the butcher room where the family prepared meat for preserving.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

FULTON

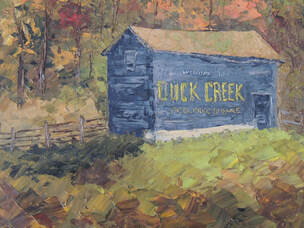

“Bean Creek”

Every now and then a name strikes me as being quintessential Americana, reminding me of times long ago – when horses were used instead of automobiled, when encyclopedias gave us information instead of a searchs on the Internet, and when people actually spoke to each other at a meal instead of studying their smart phones. The Bean Creek Valley History Center, its name displayed in gold stenciling on the center’s glass window, took me back to that era. And, of course, it was located on Main Street, actually on West Main Street, Fayette, Ohio.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Every now and then a name strikes me as being quintessential Americana, reminding me of times long ago – when horses were used instead of automobiled, when encyclopedias gave us information instead of a searchs on the Internet, and when people actually spoke to each other at a meal instead of studying their smart phones. The Bean Creek Valley History Center, its name displayed in gold stenciling on the center’s glass window, took me back to that era. And, of course, it was located on Main Street, actually on West Main Street, Fayette, Ohio.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

“Castle on the Hill”

Barn scouts Grace and Randy stopped when I asked them to – at the base of a steep hill, rising to the barn. The scene reminded me of the song, Castle on the Hill, written by Ed Sheeran and Benjamin Levin and sung by Sheeran, a popular red-haired English singer. The lyrics convey a sense of nostalgia; someone who’s now grown and returning to the land of his childhood:

And I've not seen the roaring fields in so long, I know I've grown

But I can't wait to go home …

I'm on my way

Driving at 90 down those country lanes

And we watched the sunset over the castle on the hill …

But these people raised me and I can't wait to go home

And I'm on my way

I still remember these old country lanes

When we did not know the answers …

When we watched the sunset over the castle on the hill.

My barn scouts thought that the barn might be owned by a trust associated with Wyse Plumbing and Heating. Perhaps it had been in the family for some time. Regardless, it’s well protected by five lighting rods on the roof. Behind the bank barn is a newer Gothic arch barn and to its left is a long extension and towering cement silo, hinting that in the early 1900s this was a busy place. Though we didn’t have the chance to go through the inside, I’m sure that the original farmer, had he been away from his roots for some time, would have been happy to return to his “castle on the hill.”

Barn scouts Grace and Randy stopped when I asked them to – at the base of a steep hill, rising to the barn. The scene reminded me of the song, Castle on the Hill, written by Ed Sheeran and Benjamin Levin and sung by Sheeran, a popular red-haired English singer. The lyrics convey a sense of nostalgia; someone who’s now grown and returning to the land of his childhood:

And I've not seen the roaring fields in so long, I know I've grown

But I can't wait to go home …

I'm on my way

Driving at 90 down those country lanes

And we watched the sunset over the castle on the hill …

But these people raised me and I can't wait to go home

And I'm on my way

I still remember these old country lanes

When we did not know the answers …

When we watched the sunset over the castle on the hill.

My barn scouts thought that the barn might be owned by a trust associated with Wyse Plumbing and Heating. Perhaps it had been in the family for some time. Regardless, it’s well protected by five lighting rods on the roof. Behind the bank barn is a newer Gothic arch barn and to its left is a long extension and towering cement silo, hinting that in the early 1900s this was a busy place. Though we didn’t have the chance to go through the inside, I’m sure that the original farmer, had he been away from his roots for some time, would have been happy to return to his “castle on the hill.”

“Three in One”

This farm, called the Merle Seiler farm, is now owned by Jerry and Leslie Seiler, descendants. Located in Fayette, it’s not far from the Michigan state line. For history buffs, Fayette was incorporated as a village in 1872 when the railroad reached it. A year later a post office was established and has been going strong ever since. But one of the charming aspects of this village is that it’s where the Bean Creek Valley History Center calls home. Pure Americana, the center captivated the editors of the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, so much that they included its storefront.

Judging from the condition of this well-maintained barn and the adjacent three metal silos, the farm is doing well these days. A century ago, about when the barn was built, the farmer must have also been prosperous since he connected two new barns to the original. Being connected – as many are in New England – means that the farmer could easily move from one to another in days of inclement weather. The Seilers could probably expound on the benefits of “three in one.”

This farm, called the Merle Seiler farm, is now owned by Jerry and Leslie Seiler, descendants. Located in Fayette, it’s not far from the Michigan state line. For history buffs, Fayette was incorporated as a village in 1872 when the railroad reached it. A year later a post office was established and has been going strong ever since. But one of the charming aspects of this village is that it’s where the Bean Creek Valley History Center calls home. Pure Americana, the center captivated the editors of the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, so much that they included its storefront.

Judging from the condition of this well-maintained barn and the adjacent three metal silos, the farm is doing well these days. A century ago, about when the barn was built, the farmer must have also been prosperous since he connected two new barns to the original. Being connected – as many are in New England – means that the farmer could easily move from one to another in days of inclement weather. The Seilers could probably expound on the benefits of “three in one.”

“All in the Family”

This venerable old barn is not as old as it looks; in the 1930s the owners built it to replace one that burned, never a good thing especially during the bleak days of the Great Depression. Current owners Sue and Gene Schaffner are the third generation to farm here and, judging from the three metal corn bins, two large barns, and a white pole barn (that I chose to leave out of the composition), they’re doing just fine. Their grandfather, Jacob Shaffner, started the farm in 1906, which is when he built the farmhouse.

Formerly, the family raised hogs and chickens but today they’ve switched to corn and soybeans. Their son Brent farms the 146 acres and, as the fourth generation, he’ll be in charge one day, keeping this land “all in the family.”

This venerable old barn is not as old as it looks; in the 1930s the owners built it to replace one that burned, never a good thing especially during the bleak days of the Great Depression. Current owners Sue and Gene Schaffner are the third generation to farm here and, judging from the three metal corn bins, two large barns, and a white pole barn (that I chose to leave out of the composition), they’re doing just fine. Their grandfather, Jacob Shaffner, started the farm in 1906, which is when he built the farmhouse.

Formerly, the family raised hogs and chickens but today they’ve switched to corn and soybeans. Their son Brent farms the 146 acres and, as the fourth generation, he’ll be in charge one day, keeping this land “all in the family.”

“A Botanist’s Paradise”

A few miles north of Archbold and nestled deep in woodland known as the Goll Woods State Nature Preserve is the Goll Homestead, which was listed on the National Register in 2005. Though it includes four structures, the most interesting are the 1862 farmhouse and this unique barn, built in 1865. The farm traces back to French immigrants, Peter and Catherine Goll, who moved here with their two-year-old son, Peter, Jr. in 1836 from their homeland in Alsace Lorraine, a region that bordered France and Germany and reflected both cultures.

Peter Goll, Sr. purchased 80 acres on this site from the government for $100 and he eventually increased his acreage to 600 acres. Initially, his family lived in a log cabin, but, when economics allowed, they built a conventional farmhouse and this barn. Though a tailor by trade, Peter learned the wagon making business, but decided to become a full-time farmer, as many early settlers did. The 1850 U.S. agricultural census revealed that the Golls owned

two milk cows, two oxen, four sheep, and two hogs. They also raised wheat, Indian com, oats, wool, butter, Irish potatoes, and hay, which meant that they were subsistence farmers, hoping to support their family and to barter with any excess production. The 1880 census showed that they continued to prosper – coinciding with the drainage of the swamp. Formerly, this was part of the Great Black Swamp, a lengthy area from northeastern Indiana to land east of Toledo. For cropland it was essentially useless … until a clever Ohioan invented a ditch digger to lay tile and drain the swamp. Today the black soil is some of the most fertile in the Midwest.

Though most old barns in Appalachian Ohio are traditional Pennsylvania German bank barns, with the forebay on the downslope side of the bank, this one is the opposite. Its three individual forebays are also unusual since the typical forebay extends the entire length of the barn. Perhaps this shows a German-Swiss influence but, regardless, this barn is highly unusual, one that expert Keith Sommer has called, “the rarest of the rare.” Few barns with this design still stand and most of them are located in southeastern Pennsylvania. As many farmers did when they began to prosper, the Golls altered the gable roof by converting it to a wider gambrel style sometime in the late 1800s. This provided more room for hay and grain storage.

The farm remained in family hands until the Goll’s great-granddaughter Mrs. Florence Goll Louys and her children sold the 320-acre farm to the state of Ohio in 1966. Over the years, unoccupied, the farmhouse and barn deteriorated, spurring the state to plan to demolish both. However, locals formed a non-profit, Friends of Goll Homestead, and stepped forward, raising $250,000 in grants and contributing another $10,000 to restore the buildings. Along with the state park rangers, the friends, all volunteers, help to make this homestead an educational experience.

The woods are also historic and are listed as a National Natural Landmark for a couple of reasons, but mainly because it’s one of the few remaining examples of an oak-hickory dominated forest in Ohio. Thanks to the Goll family resisting offers from timber companies, magnificent trees line this preserve, some towering over 100 feet and ranging in age from 200 to 400 years old. Gigantic white oaks, burr oaks, chinquapin oaks and cottonwoods, some of which are 200 to 400 years old, are intermingled with other species: catalpa, tulip, elm, ash, silver maple, walnut, Chinese elm, apple, and cedar. It’s a botanist’s paradise.

A few miles north of Archbold and nestled deep in woodland known as the Goll Woods State Nature Preserve is the Goll Homestead, which was listed on the National Register in 2005. Though it includes four structures, the most interesting are the 1862 farmhouse and this unique barn, built in 1865. The farm traces back to French immigrants, Peter and Catherine Goll, who moved here with their two-year-old son, Peter, Jr. in 1836 from their homeland in Alsace Lorraine, a region that bordered France and Germany and reflected both cultures.

Peter Goll, Sr. purchased 80 acres on this site from the government for $100 and he eventually increased his acreage to 600 acres. Initially, his family lived in a log cabin, but, when economics allowed, they built a conventional farmhouse and this barn. Though a tailor by trade, Peter learned the wagon making business, but decided to become a full-time farmer, as many early settlers did. The 1850 U.S. agricultural census revealed that the Golls owned

two milk cows, two oxen, four sheep, and two hogs. They also raised wheat, Indian com, oats, wool, butter, Irish potatoes, and hay, which meant that they were subsistence farmers, hoping to support their family and to barter with any excess production. The 1880 census showed that they continued to prosper – coinciding with the drainage of the swamp. Formerly, this was part of the Great Black Swamp, a lengthy area from northeastern Indiana to land east of Toledo. For cropland it was essentially useless … until a clever Ohioan invented a ditch digger to lay tile and drain the swamp. Today the black soil is some of the most fertile in the Midwest.

Though most old barns in Appalachian Ohio are traditional Pennsylvania German bank barns, with the forebay on the downslope side of the bank, this one is the opposite. Its three individual forebays are also unusual since the typical forebay extends the entire length of the barn. Perhaps this shows a German-Swiss influence but, regardless, this barn is highly unusual, one that expert Keith Sommer has called, “the rarest of the rare.” Few barns with this design still stand and most of them are located in southeastern Pennsylvania. As many farmers did when they began to prosper, the Golls altered the gable roof by converting it to a wider gambrel style sometime in the late 1800s. This provided more room for hay and grain storage.

The farm remained in family hands until the Goll’s great-granddaughter Mrs. Florence Goll Louys and her children sold the 320-acre farm to the state of Ohio in 1966. Over the years, unoccupied, the farmhouse and barn deteriorated, spurring the state to plan to demolish both. However, locals formed a non-profit, Friends of Goll Homestead, and stepped forward, raising $250,000 in grants and contributing another $10,000 to restore the buildings. Along with the state park rangers, the friends, all volunteers, help to make this homestead an educational experience.

The woods are also historic and are listed as a National Natural Landmark for a couple of reasons, but mainly because it’s one of the few remaining examples of an oak-hickory dominated forest in Ohio. Thanks to the Goll family resisting offers from timber companies, magnificent trees line this preserve, some towering over 100 feet and ranging in age from 200 to 400 years old. Gigantic white oaks, burr oaks, chinquapin oaks and cottonwoods, some of which are 200 to 400 years old, are intermingled with other species: catalpa, tulip, elm, ash, silver maple, walnut, Chinese elm, apple, and cedar. It’s a botanist’s paradise.

“Prosperity”

There’s a lot to this meticulously maintained old barn: devil doors, louvered ventilators, a small add-on shed, a pent roof overhang, and a 3x4-foot quilt design. Under the name, S.S. Wyse, on the end of the barn is the date 1893, which may signify when the barn was built or when the farm was founded. Regardless, the farmer knew his business since his productivity meant a need for more space; in response he added an entire barn, connecting it at a right angle to the original. Today’s owners have kept the founder’s legacy alive, adding a fresh coat of red paint, paying attention to white borders for the devil doors, and adding a new twist, the quilt. Decades ago, even during the horrible years of the Great Depression, this farmer kept going, enhancing the barn, according to the farm’s needs. Indeed, he knew the meaning of prosperity.

There’s a lot to this meticulously maintained old barn: devil doors, louvered ventilators, a small add-on shed, a pent roof overhang, and a 3x4-foot quilt design. Under the name, S.S. Wyse, on the end of the barn is the date 1893, which may signify when the barn was built or when the farm was founded. Regardless, the farmer knew his business since his productivity meant a need for more space; in response he added an entire barn, connecting it at a right angle to the original. Today’s owners have kept the founder’s legacy alive, adding a fresh coat of red paint, paying attention to white borders for the devil doors, and adding a new twist, the quilt. Decades ago, even during the horrible years of the Great Depression, this farmer kept going, enhancing the barn, according to the farm’s needs. Indeed, he knew the meaning of prosperity.

“Serenely Sly”

This barn traces back to the 1890s when Lyndon and Edna Sly owned the farm. Originally, they added a wooden silo, which preceded the metal and cement varieties. Unfortunately, it’s no longer standing.

The farm continued in family hands, when Don Sly and his father farmed roughly 1,000 acres, a large farm even in the 1940s. Sadly Don passed away in 2021, leaving the farm to his widow Grace, whom we met on our visit in 2023. Grace told us that her father-in-law built the lengthy wood and cement block addition that wraps around two sides of the barn. Interestingly, he built it in 1938, during the end of the Great Depression, years that were difficult not only for farmers but also for those in cities where unemployment had reached 25 percent.

Though today’s acreage has shrunk to 100 acres, which Grace rents to tenant farmers, the barn still represents the family heritage and, as such, is serenely Sly.

This barn traces back to the 1890s when Lyndon and Edna Sly owned the farm. Originally, they added a wooden silo, which preceded the metal and cement varieties. Unfortunately, it’s no longer standing.

The farm continued in family hands, when Don Sly and his father farmed roughly 1,000 acres, a large farm even in the 1940s. Sadly Don passed away in 2021, leaving the farm to his widow Grace, whom we met on our visit in 2023. Grace told us that her father-in-law built the lengthy wood and cement block addition that wraps around two sides of the barn. Interestingly, he built it in 1938, during the end of the Great Depression, years that were difficult not only for farmers but also for those in cities where unemployment had reached 25 percent.

Though today’s acreage has shrunk to 100 acres, which Grace rents to tenant farmers, the barn still represents the family heritage and, as such, is serenely Sly.

“Freedom”

From a distance, though this well-cared for barn is impressive, the two towering gray cement silos dominate the scene. Built most likely in the early 1900s, they certainly prove that the farm was highly productive. Which came first? The bigger one?

Barn scouts Grace and Randy introduced me to barn owner Joy Graf, whose name is clearly displayed in white block lettering on the barn’s end and just above “Mill Creek Stock Farm.” Joy told us that she taught kindergarten in the years when prayer was allowed in school. However, when a parent complained, the principal told Joy to stop the prayers.

So, at 70, she built a pre-school building next to the farmhouse and ran the school – with prayers allowed. Funny, in 1791 Congress passed the famous Bill of Rights, which included the first amendment, one that guaranteed freedom of religion and freedom of speech. How quickly we forget what our forefathers fought for in the American Revolution.

From a distance, though this well-cared for barn is impressive, the two towering gray cement silos dominate the scene. Built most likely in the early 1900s, they certainly prove that the farm was highly productive. Which came first? The bigger one?

Barn scouts Grace and Randy introduced me to barn owner Joy Graf, whose name is clearly displayed in white block lettering on the barn’s end and just above “Mill Creek Stock Farm.” Joy told us that she taught kindergarten in the years when prayer was allowed in school. However, when a parent complained, the principal told Joy to stop the prayers.

So, at 70, she built a pre-school building next to the farmhouse and ran the school – with prayers allowed. Funny, in 1791 Congress passed the famous Bill of Rights, which included the first amendment, one that guaranteed freedom of religion and freedom of speech. How quickly we forget what our forefathers fought for in the American Revolution.

“Fabulous Fahringer”

There’s no question that this magnificent barn is one of the most attractive in Fulton County. Meticulously maintained by the Fahringer family, its Indian red paint shows hardly any wear and, protected by eight lightning rods, the barn will be around for some time.

Two commanding Louden metal ventilators sit high on the roofline and three imposing dormers provide plenty of light, thanks to eight-on-eight windows. But the most striking feature of the barn is its gothic arch roof.

As American farmers became more prosperous, they needed more storage space in their barns and they found that the gambrel roof solved this problem. This double pitch design was first used in colonial houses in the late 1700s, though it didn’t become popular in barns until after the Civil War. Some farmers cleverly altered their roofs, converting a simple two-sided gable to a gambrel roof. Beats building a new barn from scratch.

The gothic arch roof for barns originated in Michigan in the late 19th-century, though most farmers stuck to the gable roof or the gambrel. John L. Shawver of Ohio’s Logan County invented the Shawver truss in 1904, which was less expensive than traditional timber-framed structures and opened the hayloft for more storage, especially in the gambrel roof design. Shawver’s use of laminated boards helped barns evolve into the curved gothic roof design, which allowed even more storage space. In a 1916 issue of the Idaho Farmer magazine editors predicted that the gothic arch barn “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy farms.” However, farmers continued to stick with the gable and gambrel roof styles. Even today, spotting a gothic arch barn is rare in most regions.

Hopefully, this barn will continue to stand – in full sight from the road – allowing passing motorists a view and interested photographers and artists a chance to capture its fabulous image.

There’s no question that this magnificent barn is one of the most attractive in Fulton County. Meticulously maintained by the Fahringer family, its Indian red paint shows hardly any wear and, protected by eight lightning rods, the barn will be around for some time.

Two commanding Louden metal ventilators sit high on the roofline and three imposing dormers provide plenty of light, thanks to eight-on-eight windows. But the most striking feature of the barn is its gothic arch roof.

As American farmers became more prosperous, they needed more storage space in their barns and they found that the gambrel roof solved this problem. This double pitch design was first used in colonial houses in the late 1700s, though it didn’t become popular in barns until after the Civil War. Some farmers cleverly altered their roofs, converting a simple two-sided gable to a gambrel roof. Beats building a new barn from scratch.

The gothic arch roof for barns originated in Michigan in the late 19th-century, though most farmers stuck to the gable roof or the gambrel. John L. Shawver of Ohio’s Logan County invented the Shawver truss in 1904, which was less expensive than traditional timber-framed structures and opened the hayloft for more storage, especially in the gambrel roof design. Shawver’s use of laminated boards helped barns evolve into the curved gothic roof design, which allowed even more storage space. In a 1916 issue of the Idaho Farmer magazine editors predicted that the gothic arch barn “would become the most prevalent construction type built on successful dairy farms.” However, farmers continued to stick with the gable and gambrel roof styles. Even today, spotting a gothic arch barn is rare in most regions.

Hopefully, this barn will continue to stand – in full sight from the road – allowing passing motorists a view and interested photographers and artists a chance to capture its fabulous image.

“The Green Silo”

Sadly, this old barn will likely be gone by the time I paint its picture and write its essay. And it’s old, probably built before the Civil War. The Hoyt family founded this farm in 1858 and may have built the barn. They sold it to the Sauerbecks in 1875 and then it was purchased around 1900 by the Winzelers, whose name is fading away on siding above the entrance.

The size of this large bank barn hints that the owners had a prosperous farming enterprise and, if they hired a barn builder, they hired a good one. Full of hand-hewn beams, presumably harvested from the farm, the barn testifies that the timber-framer knew his business. Remarkably, the mortise and tenon joints, connected by wooden pegs, show little wear, now 170 years later. Another relic of the past, a hand-crafted wooden ladder, leads to the second floor haymow. Though the red and white paint have faded on the siding, the devil door outlines can still be seen – a common sight on barns in this region of Ohio and northeastern Indiana.

But the crowning jewel of this barn, owned by Kyle Miller, who purchased it in 2021, is the metal silo, probably added circa 1900. Curiously, the farmer first painted it red, and then later he covered it with green, which has faded into a warm shade of avocado, incredibly esthetic and rare. Perhaps the farmer had a background in art, choosing complementary colors – green and red – in the green silo and red barn. As any artist knows, placing complementary colors next to each other gives a dramatic look. Though the green and red colors have faded, the handsome barn will be recorded in this essay and painting, which focuses on something seldom seen - a green silo.

Sadly, this old barn will likely be gone by the time I paint its picture and write its essay. And it’s old, probably built before the Civil War. The Hoyt family founded this farm in 1858 and may have built the barn. They sold it to the Sauerbecks in 1875 and then it was purchased around 1900 by the Winzelers, whose name is fading away on siding above the entrance.

The size of this large bank barn hints that the owners had a prosperous farming enterprise and, if they hired a barn builder, they hired a good one. Full of hand-hewn beams, presumably harvested from the farm, the barn testifies that the timber-framer knew his business. Remarkably, the mortise and tenon joints, connected by wooden pegs, show little wear, now 170 years later. Another relic of the past, a hand-crafted wooden ladder, leads to the second floor haymow. Though the red and white paint have faded on the siding, the devil door outlines can still be seen – a common sight on barns in this region of Ohio and northeastern Indiana.

But the crowning jewel of this barn, owned by Kyle Miller, who purchased it in 2021, is the metal silo, probably added circa 1900. Curiously, the farmer first painted it red, and then later he covered it with green, which has faded into a warm shade of avocado, incredibly esthetic and rare. Perhaps the farmer had a background in art, choosing complementary colors – green and red – in the green silo and red barn. As any artist knows, placing complementary colors next to each other gives a dramatic look. Though the green and red colors have faded, the handsome barn will be recorded in this essay and painting, which focuses on something seldom seen - a green silo.

“A Drummer Boy”

There’s an earthen bank on the rear side of this well-maintained old barn, owned by Bill Roth. Adjacent flat, fertile farm fields, a towering cement silo, and a significant add-on shed hint that this farm was prosperous.

However, as impressive as the barn is, its farmhouse story may take the prize. According to barn scouts Grace and Randy, the Grand Army of the Republic once stayed at the farmhouse around 1900. Not many know what this army once was, but it’s a tale worth telling.

After the bloody Civil War, many veterans formed groups, both for camaraderie and for networking. The most influential of these was the Grand Army of the Republic, founded in 1866 on the principles of “fraternity, charity, and loyalty.” Membership was limited to both white and black soldiers, sailors, and marines of the Union Army. Though, as a result of its lack of commitment to reforming the Jim Crow South, it almost dissolved in the early 1870s, it continued and grew into a political power, allied with the Republican Party.

Its membership peaked at about 410,000 members in 1890 – with hundreds of posts throughout the north and west – and it helped elect six presidents: Ulysses Grant, Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley. All were Republicans.

In 1868 its commander-in-chief, General John A. Logan, proposed a special day to honor war casualties, deceased veterans, and those missing in action – with an emphasis on decorating their graves. The GAR chose May 30 as this special day, which is now a federal holiday, known as Memorial Day.

As Union veterans died off, the GAR’s membership dwindled until its last member died in 1956, ending this nearly-century-old organization. Albert Woolson, the last surviving member of the Union Army, died at 106 in 1956 and with his death the GAR was formally dissolved. Albert served at age 14 as a drummer boy for the Union Army in 1864. Did this former drummer boy attend the conference in this barn? As Hemingway once wrote, “Isn't it pretty to think so?”

There’s an earthen bank on the rear side of this well-maintained old barn, owned by Bill Roth. Adjacent flat, fertile farm fields, a towering cement silo, and a significant add-on shed hint that this farm was prosperous.

However, as impressive as the barn is, its farmhouse story may take the prize. According to barn scouts Grace and Randy, the Grand Army of the Republic once stayed at the farmhouse around 1900. Not many know what this army once was, but it’s a tale worth telling.

After the bloody Civil War, many veterans formed groups, both for camaraderie and for networking. The most influential of these was the Grand Army of the Republic, founded in 1866 on the principles of “fraternity, charity, and loyalty.” Membership was limited to both white and black soldiers, sailors, and marines of the Union Army. Though, as a result of its lack of commitment to reforming the Jim Crow South, it almost dissolved in the early 1870s, it continued and grew into a political power, allied with the Republican Party.

Its membership peaked at about 410,000 members in 1890 – with hundreds of posts throughout the north and west – and it helped elect six presidents: Ulysses Grant, Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley. All were Republicans.

In 1868 its commander-in-chief, General John A. Logan, proposed a special day to honor war casualties, deceased veterans, and those missing in action – with an emphasis on decorating their graves. The GAR chose May 30 as this special day, which is now a federal holiday, known as Memorial Day.

As Union veterans died off, the GAR’s membership dwindled until its last member died in 1956, ending this nearly-century-old organization. Albert Woolson, the last surviving member of the Union Army, died at 106 in 1956 and with his death the GAR was formally dissolved. Albert served at age 14 as a drummer boy for the Union Army in 1864. Did this former drummer boy attend the conference in this barn? As Hemingway once wrote, “Isn't it pretty to think so?”

“Peter’s Place”

This farm has been in family hands ever since it was founded in the years well before the Civil War. The legacy traces back to Peter Short, also known as “Doddy,” a German nickname for grandfather. Born in 1826 in Germany, Peter emigrated with his parents to America when he was 10. They settled in Fulton County as many of their fellow countrymen did.

He married Barbara Lauber and the couple had their first child, Maglina, in 1848. Twelve more children would follow, a lot of mouths to feed but typical of 19th-century farm families. Only five of the 13 were sons; so Peter didn’t get a lot of help for the strenuous farm chores. By this time it’s likely he had built the barn.

In German tradition, Peter built a two-level barn and, since he couldn’t use a hillside, he ramped up earth into a bank, where wagons could enter the second floor. Today, current owners Doug and Michele Noziger have maintained the old barn well. In fact, they’ve added another one, more modern, to keep up with the needs of the farm.

In chapter 27 of his book, The Days of My Years, Walter E. Stuckey related a few stories about Peter, his great grandfather. As many German immigrants, they were Amish. And they offered the use of their large barn for religious conferences. The last one was held in 1878 and apparently it was a large one, drawing participants from far and wide. Interestingly, at that meeting the community decided to leave the ways of the Old Amish Order and change to the more progressive Mennonite branch.

He also shared stories about tramps, hobos, or, as Roger Miller sang about in his song King of the Road:

Trailer’s for sale or rent

Rooms to let, 50 cents

No phone, no pool, no pets

I ain't got no cigarettes

Ah, but, two hours of pushin’ broom

Buys an eight by twelve four-bit room

I'm a man of means by no means

King of the road …

In the 1800s and early 1900s, rules were lax on hitching free rides on the railroad and many kings of the road took advantage of this free transportation to move from one location to another. And, in Fulton County, Stuckey explained that many farmers had to lock their doors when they went on errands so that a hobo wouldn’t take advantage of an open house. In fact, on one occasion Peter woke from his sleep to find a tramp going through his trousers, looking for cash. He grabbed him, took him upstairs to an empty room, locked the door, and went back to sleep. The next morning, he opened the door, fed him breakfast, and sent him on his way, certainly a more humane reaction than calling the police and hauling him off to jail. But life was much different in those days.

Indeed it’s rare that a family can keep the farm continuously for over 150 years. Hopefully the Nofzigers will continue to hold it as the farm approaches bicentennial status. I’m sure that Peter would agree.

This farm has been in family hands ever since it was founded in the years well before the Civil War. The legacy traces back to Peter Short, also known as “Doddy,” a German nickname for grandfather. Born in 1826 in Germany, Peter emigrated with his parents to America when he was 10. They settled in Fulton County as many of their fellow countrymen did.

He married Barbara Lauber and the couple had their first child, Maglina, in 1848. Twelve more children would follow, a lot of mouths to feed but typical of 19th-century farm families. Only five of the 13 were sons; so Peter didn’t get a lot of help for the strenuous farm chores. By this time it’s likely he had built the barn.

In German tradition, Peter built a two-level barn and, since he couldn’t use a hillside, he ramped up earth into a bank, where wagons could enter the second floor. Today, current owners Doug and Michele Noziger have maintained the old barn well. In fact, they’ve added another one, more modern, to keep up with the needs of the farm.

In chapter 27 of his book, The Days of My Years, Walter E. Stuckey related a few stories about Peter, his great grandfather. As many German immigrants, they were Amish. And they offered the use of their large barn for religious conferences. The last one was held in 1878 and apparently it was a large one, drawing participants from far and wide. Interestingly, at that meeting the community decided to leave the ways of the Old Amish Order and change to the more progressive Mennonite branch.

He also shared stories about tramps, hobos, or, as Roger Miller sang about in his song King of the Road:

Trailer’s for sale or rent

Rooms to let, 50 cents

No phone, no pool, no pets

I ain't got no cigarettes

Ah, but, two hours of pushin’ broom

Buys an eight by twelve four-bit room

I'm a man of means by no means

King of the road …

In the 1800s and early 1900s, rules were lax on hitching free rides on the railroad and many kings of the road took advantage of this free transportation to move from one location to another. And, in Fulton County, Stuckey explained that many farmers had to lock their doors when they went on errands so that a hobo wouldn’t take advantage of an open house. In fact, on one occasion Peter woke from his sleep to find a tramp going through his trousers, looking for cash. He grabbed him, took him upstairs to an empty room, locked the door, and went back to sleep. The next morning, he opened the door, fed him breakfast, and sent him on his way, certainly a more humane reaction than calling the police and hauling him off to jail. But life was much different in those days.

Indeed it’s rare that a family can keep the farm continuously for over 150 years. Hopefully the Nofzigers will continue to hold it as the farm approaches bicentennial status. I’m sure that Peter would agree.

“1891”

Although it’s hard to make out from a distance, upon closer inspection, the date of 1891 can be clearly seen in this slate roof. Slate, more often seen in barns in northeastern Ohio, was expensive in the late 19th century and the first few decades of the following year, the heyday of this durable roof covering. It showed that the barn owner could afford it and, even more, that he was proud of the date of his farm, though sometimes the date referred to the barn only. In this case the extended entrance was also covered in slate.

Barn scouts Grace and Randy explained that the McQuillen Trust owns this farm, not far from Wauseon, the county seat of Fulton County. The owners have maintained the 130-year-old barn exceptionally well, protecting it with bright red metal siding and lighting rods. The brooding cement silo and the slate roofs continue to hold up well, preserving the legacy of this old barn and its date of 1891.

Although it’s hard to make out from a distance, upon closer inspection, the date of 1891 can be clearly seen in this slate roof. Slate, more often seen in barns in northeastern Ohio, was expensive in the late 19th century and the first few decades of the following year, the heyday of this durable roof covering. It showed that the barn owner could afford it and, even more, that he was proud of the date of his farm, though sometimes the date referred to the barn only. In this case the extended entrance was also covered in slate.

Barn scouts Grace and Randy explained that the McQuillen Trust owns this farm, not far from Wauseon, the county seat of Fulton County. The owners have maintained the 130-year-old barn exceptionally well, protecting it with bright red metal siding and lighting rods. The brooding cement silo and the slate roofs continue to hold up well, preserving the legacy of this old barn and its date of 1891.

“Brick and Thistle”

This is the main barn on the farm owned by Chris Rupp, who married Dean Richardson in 2015. For her, this was homecoming since her roots lie in Fulton County; but for Dean, a resident of Miami, Florida, a town not known for cold winters, it was a radical change. Together, they have begun a transformation of this old farmstead into a lively agricultural experience.

They plan to convert the wooden corn crib into a wedding chapel, the summer kitchen into an Air B&B, the chicken barn (Lou’s Lair) into a country store, and this old barn into an event center. In addition, Dean, with a background in marine biology and a passion for plants, has built a gigantic greenhouse, where he raises, among other things, a delicious herb called French Sorrell, which can be used in salads, soups, and sauces. In April, 2023, they held a fundraiser for the history center, which included me doing a demo painting of the chicken barn.

Louis Merillat, grandfather of Chris, founded the farm in the 1890s and her mother, Loueen, was born in the still extant farmhouse. Loueen married Howard Rupp and they continued to farm the land. In 1968 Louis Merrilat, Christine’s grandfather, died and, with his demise, the farm slid out of family hands when the Leu family bought it at an auction two years later. Unfortunately, over the years, the buildings deteriorated and, though Chris wanted to buy it back many years ago, it wasn’t for sale. Then, fortune smiled and in 2005 Chris was able to purchase her family’s farm.

The large barn served the family well for many decades as they farmed crops and raised cattle and dairy cows, evidenced by the stanchions still present in the main barn. Inside, hand-hewn beams, connected with mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs, suggest a construction date in the late 1800s. The barn also features several sets of devil doors, commonly used on barns in northwestern Ohio, although this barn’s doors have a distinctive twist to them – a round circle in the middle.

As part of their plan, Chris and Dean have renamed the farmstead – the Brick and Thistle Farm. As they continue to rehab the buildings, a time approaches when the farm will be a thriving endeavor, making her grandfather, Louis, swell with pride.

This is the main barn on the farm owned by Chris Rupp, who married Dean Richardson in 2015. For her, this was homecoming since her roots lie in Fulton County; but for Dean, a resident of Miami, Florida, a town not known for cold winters, it was a radical change. Together, they have begun a transformation of this old farmstead into a lively agricultural experience.

They plan to convert the wooden corn crib into a wedding chapel, the summer kitchen into an Air B&B, the chicken barn (Lou’s Lair) into a country store, and this old barn into an event center. In addition, Dean, with a background in marine biology and a passion for plants, has built a gigantic greenhouse, where he raises, among other things, a delicious herb called French Sorrell, which can be used in salads, soups, and sauces. In April, 2023, they held a fundraiser for the history center, which included me doing a demo painting of the chicken barn.

Louis Merillat, grandfather of Chris, founded the farm in the 1890s and her mother, Loueen, was born in the still extant farmhouse. Loueen married Howard Rupp and they continued to farm the land. In 1968 Louis Merrilat, Christine’s grandfather, died and, with his demise, the farm slid out of family hands when the Leu family bought it at an auction two years later. Unfortunately, over the years, the buildings deteriorated and, though Chris wanted to buy it back many years ago, it wasn’t for sale. Then, fortune smiled and in 2005 Chris was able to purchase her family’s farm.

The large barn served the family well for many decades as they farmed crops and raised cattle and dairy cows, evidenced by the stanchions still present in the main barn. Inside, hand-hewn beams, connected with mortise and tenon joints, held with wooden pegs, suggest a construction date in the late 1800s. The barn also features several sets of devil doors, commonly used on barns in northwestern Ohio, although this barn’s doors have a distinctive twist to them – a round circle in the middle.

As part of their plan, Chris and Dean have renamed the farmstead – the Brick and Thistle Farm. As they continue to rehab the buildings, a time approaches when the farm will be a thriving endeavor, making her grandfather, Louis, swell with pride.

GALLIA

“Bob’s Place”

Nestled in the hills of another of Ohio’s Appalachian counties is the Bob Evans Farm, which furnished the barn for Ohio’s bicentennial logo painting and which, I thought, would be a good one for my Ohio Barn Project as well. Though I had planned to visit during their annual farm festival – which attracts 30,000 – I reconsidered and visited a week earlier. Even then, tents and trailers lined the grassy fields beneath the old barn and this old homestead, as it prepared to host hordes of visitors. My grandson Henry and I visited this iconic homestead on a sunny October morning, one with relatively few cars in the parking lot.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

Nestled in the hills of another of Ohio’s Appalachian counties is the Bob Evans Farm, which furnished the barn for Ohio’s bicentennial logo painting and which, I thought, would be a good one for my Ohio Barn Project as well. Though I had planned to visit during their annual farm festival – which attracts 30,000 – I reconsidered and visited a week earlier. Even then, tents and trailers lined the grassy fields beneath the old barn and this old homestead, as it prepared to host hordes of visitors. My grandson Henry and I visited this iconic homestead on a sunny October morning, one with relatively few cars in the parking lot.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

GEAUGA

“Trophy Husband”

After exploring Ashtabula and Trumbull counties years ago, I was anxious to see Geauga County and its barns, especially because the name of the county traces back to “Sheauga,” meaning “raccoon,” a name the Native tribes gave to the rivers in this part, notably the Grand River, which begins in this county and eventually empties into Lake Erie. The local historical society put me in touch with Dee Belew, who wanted me to see her barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

After exploring Ashtabula and Trumbull counties years ago, I was anxious to see Geauga County and its barns, especially because the name of the county traces back to “Sheauga,” meaning “raccoon,” a name the Native tribes gave to the rivers in this part, notably the Grand River, which begins in this county and eventually empties into Lake Erie. The local historical society put me in touch with Dee Belew, who wanted me to see her barn.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

GREENE

"Caesar's Freedom"

This is yet another barn tracing to the Spahr family. One must wonder why, in 1749, that Hans Ulrich Spahr left Basil, Switzerland with his wife Margaret Seyler Spahr and 12 children to immigrate to America, then mostly a British colony, though the French and Spanish both had their hooks in the new land. But, like so many Europeans, they might have felt they’d have a better life in the new country.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

This is yet another barn tracing to the Spahr family. One must wonder why, in 1749, that Hans Ulrich Spahr left Basil, Switzerland with his wife Margaret Seyler Spahr and 12 children to immigrate to America, then mostly a British colony, though the French and Spanish both had their hooks in the new land. But, like so many Europeans, they might have felt they’d have a better life in the new country.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

"The Legacy"

Mary Spahr, my Greene County barn scout, contacted me in the summer of 2016 when she discovered, by pure chance, that an essay of mine about a barn and farm in Highland County had some incorrect information. I won’t go into detail about this – since it’s involved – but it acquainted Mary with my work and prompted her to ask me to paint barns in her county – for a fundraiser. And Mary’s lineage and that of her husband Jim goes back a long way. Mary’s kin trace back to when her ancestors came to Highland County in the late 1700s but Jim’s roots run deep in Greene County, evidenced by the road where they live that bears the Spahr name. Click here for the rest of the story.

Mary Spahr, my Greene County barn scout, contacted me in the summer of 2016 when she discovered, by pure chance, that an essay of mine about a barn and farm in Highland County had some incorrect information. I won’t go into detail about this – since it’s involved – but it acquainted Mary with my work and prompted her to ask me to paint barns in her county – for a fundraiser. And Mary’s lineage and that of her husband Jim goes back a long way. Mary’s kin trace back to when her ancestors came to Highland County in the late 1700s but Jim’s roots run deep in Greene County, evidenced by the road where they live that bears the Spahr name. Click here for the rest of the story.

GUERNSEY

“Labor of Love”

I’ve done paintings of a lot of old barns that feature the Harley Warrick Mail Pouch logo, but I’ve never seen it on a covered bridge. So, during my drive out of Muskingum County – after painting the barn owned by the McDonalds – I passed through a thin slice of Guernsey County and saw this oddity. Even though I had a long drive ahead of me to Perry County and its three round barns, I had to stop for a look. Yes, methinks, this is not a barn, but it’s still an Ohio treasure – a covered bridge with Harley’s imprint. So I pulled off to the side of the road, did a value sketch, and took photos, hoping to discover a story later.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

I’ve done paintings of a lot of old barns that feature the Harley Warrick Mail Pouch logo, but I’ve never seen it on a covered bridge. So, during my drive out of Muskingum County – after painting the barn owned by the McDonalds – I passed through a thin slice of Guernsey County and saw this oddity. Even though I had a long drive ahead of me to Perry County and its three round barns, I had to stop for a look. Yes, methinks, this is not a barn, but it’s still an Ohio treasure – a covered bridge with Harley’s imprint. So I pulled off to the side of the road, did a value sketch, and took photos, hoping to discover a story later.

The rest of this story is featured in the book, Historic Barns of Ohio, available at most bookstores and through online sellers, including the publisher, the History Press.

HAMILTON

“Montgomery’s Puzzle”

Finding this old barn represents the meaning of serendipity in its truest sense. In early September, 2020, my wife Laura asked me to enter our suburb’s annual holiday art contest. My reply was that I was heavily involved in a project on America’s round barns. Her reply was that Montgomery had plenty of old historic buildings. My reply was that I just wasn’t interested.

After a week of guilty feelings, I remembered seeing an old barn across the road from where my late wife and I raised our children in the 1980s. I wondered if it happened to be still standing. A few days later, I drove by, delighted to see it again. From a distance, the barn – nothing special at first sight – appeared to be circa early 20th century. Nothing special, I thought, but worth checking out. So I approached a group of men near the barn and asked if one was the owner. “Yes, I am,” one of them replied. After explaining my Ohio Barn Project, I asked if he’d take me inside. As we entered through the tiny door-inside-the-big door (often called a “man-door”), a rarity in old barns, a throwback to medieval times when wickets were used, small, narrow doors inside or next to either a castle’s large double doors or the entry gates of a city. In the case of an old barn, entering through a “man door” would be easier than trying to pull open large barn doors, especially in inclement weather. The long iron hinges were old, too.

Once inside, I couldn’t believe my eyes. The entire barn, a small two-bay English one, typical of the pre-Civil War era in the Midwest, was timber-framed: hand-hewn oak beams, some 30-50 feet long, mortise and tenon joints, and wooden pegs, still in place after 150-200 years. I told Tom Baker, the new owner at the time, that this barn was extremely historic, especially in a suburb, where houses built in the 1960s were being torn down – due to lack of vacant lots – for larger contemporary homes. CLICK HERE FOR THE REST OF THE STORY

Finding this old barn represents the meaning of serendipity in its truest sense. In early September, 2020, my wife Laura asked me to enter our suburb’s annual holiday art contest. My reply was that I was heavily involved in a project on America’s round barns. Her reply was that Montgomery had plenty of old historic buildings. My reply was that I just wasn’t interested.